The pace of change increased dramatically for Tennesseans after 1945, especially for farmers. Ex-servicemen who had earned regular paychecks and seen other parts of the world simply were not willing to return to the backbreaking, mule-powered farm labor of the old days. Less risky, better-paying jobs were now available. Mechanization came late to Tennessee farms, but once it began, the changeover was rapid. The number of tractors in the state doubled during the war and increased almost ten times between 1940 and 1960. Soybeans, dairy cattle, and burley tobacco replaced the old regime of cotton, corn, and hogs as Tennessee’s main agricultural products.

Technological change was sweeping the countryside, bringing higher productivity but raising the cost of farming. New livestock breeds, fertilizers, better seed, chemical pesticides and herbicides, electricity, and machinery all combined to increase output, but the costs were more than many small farmers could afford. By the 1950s, thousands of Tennesseans had left the farms for cities. Many local Tennessee papers ran regular news columns from places like Detroit and Chicago. From a farm population that stood at 1.2 million in 1930, only 317,000 remained on farms in 1970. By 1980, fewer than six percent of Tennesseans earned their main income from farming.

As it became harder to earn a living in rural areas, Tennessee’s cities and towns continued to grow. In 1960, the state had more urban than rural dwellers for the first time. The postwar baby boom boosted growth in Tennessee’s four major cities. The demands of military production had brought several large industries to Tennessee. The Atomic Energy Commission facilities at Oak Ridge and the Arnold Engineering Center at Tullahoma remained in operation after the war. Chemicals and apparel led manufacturing growth between 1955 and 1965, a decade in which Tennessee made greater industrial gains than any other state. Inexpensive electricity, abundant resources, and a workforce no longer tied to the land encouraged rapid industrialization. By 1963, Tennessee ranked as the sixteenth-largest industrial state—a remarkable transformation for a state that, not so long ago, had been overwhelmingly agricultural.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) played a major role in the state’s postwar development. TVA supplied power for a number of military projects during the Cold War. The Cold War was the ongoing rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that developed after World War II. This period was characterized by intense propaganda campaigns, espionage or spying, and a nuclear arms race. By the time of the Korean War, over half of the power produced by TVA was being used by the government’s uranium enrichment facilities at Oak Ridge. To meet these growing power demands, TVA built eleven coal-fired, steam-generating plants between 1950 and 1970, including several of the largest steam plants in the world. Feeding these huge plants turned TVA into the nation’s foremost consumer of strip-mined coal, forced a series of electrical rate hikes, and made the agency the target of numerous lawsuits over air pollution. TVA’s venture into nuclear power increased its environmental troubles. By 1975, TVA had become the non-communist world’s largest producer of nuclear power. However, cost overruns and safety problems closed down eleven of TVA’s reactors and turned the bulk of the nuclear program into a costly write-off. Although it continues to serve as the Tennessee Valley’s unique public utility, TVA has reduced both the size and the scope of its mission.

Returning servicemen and women helped bring about a change of the old political order in Tennessee. On primary election day in Athens on August 1, 1946, a battle occurred between former soldiers and the supporters of the entrenched political machine in McMinn County. For more than six hours, the streets of Athens blazed with gunfire as armed veterans laid siege to the jail where the sheriff and fifty “deputies” were planning to stuff the ballot boxes. The sheriff and deputies surrendered after the ex-servicemen threw dynamite at the jail. When the votes were counted, the candidates backed by the ex-servicemen had won clear victories. The so-called “Battle of Athens” actually represented the beginning of a statewide political cleanup. Local bosses were challenged by reformers who wanted to bring an end to the power of political machines. The veterans’ victory demonstrated to Congressman Estes Kefauver and other up-and-coming politicians that the old style of Tennessee politics was about to change.

In the 1948 elections, Kefauver won a U.S. Senate seat, and former Governor Gordon Browning returned as Tennessee’s governor with the help of veterans’ votes. The men defeated handpicked candidates of Memphis Mayor Ed Crump. The Kefauver and Browning victories spelled the end of “Boss” Crump’s twenty-year control of state politics. Although Crump continued to exert a powerful influence in the affairs of the Shelby County Democratic Party, he never again called the shots in statewide elections. The 1953 limited constitutional convention dealt a further blow to machine politics by repealing the state poll tax, a key element in politicians’ ability to limit and manipulate the vote.

Round two of the changing of the political guard came in 1952, when Albert Gore, Sr., defeated eighty-five-year-old Kenneth D. McKellar for the Senate seat that McKellar had held for thirty-six years. That same year, Governor Browning himself was defeated by a rising young political star from Dickson County, Frank Goad Clement. The constitutional revision had changed the governor’s term from two to four years. Either Clement or his friend and campaign manager, Buford Ellington, would occupy the governor’s mansion for the next twenty years. Clement, Gore, and Kefauver represented a moderate wing of the Southern Democrats. For example, Kefauver and Gore refused to sign the segregationist Southern Manifesto of 1956. Kefauver also opposed Senator Joseph McCarthy. In 1954, Kefauver was the only senator to vote against making it a crime to belong to the Communist Party. In 1956, Governor Clement delivered the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention, the same convention that named Kefauver as the party’s vice presidential candidate.

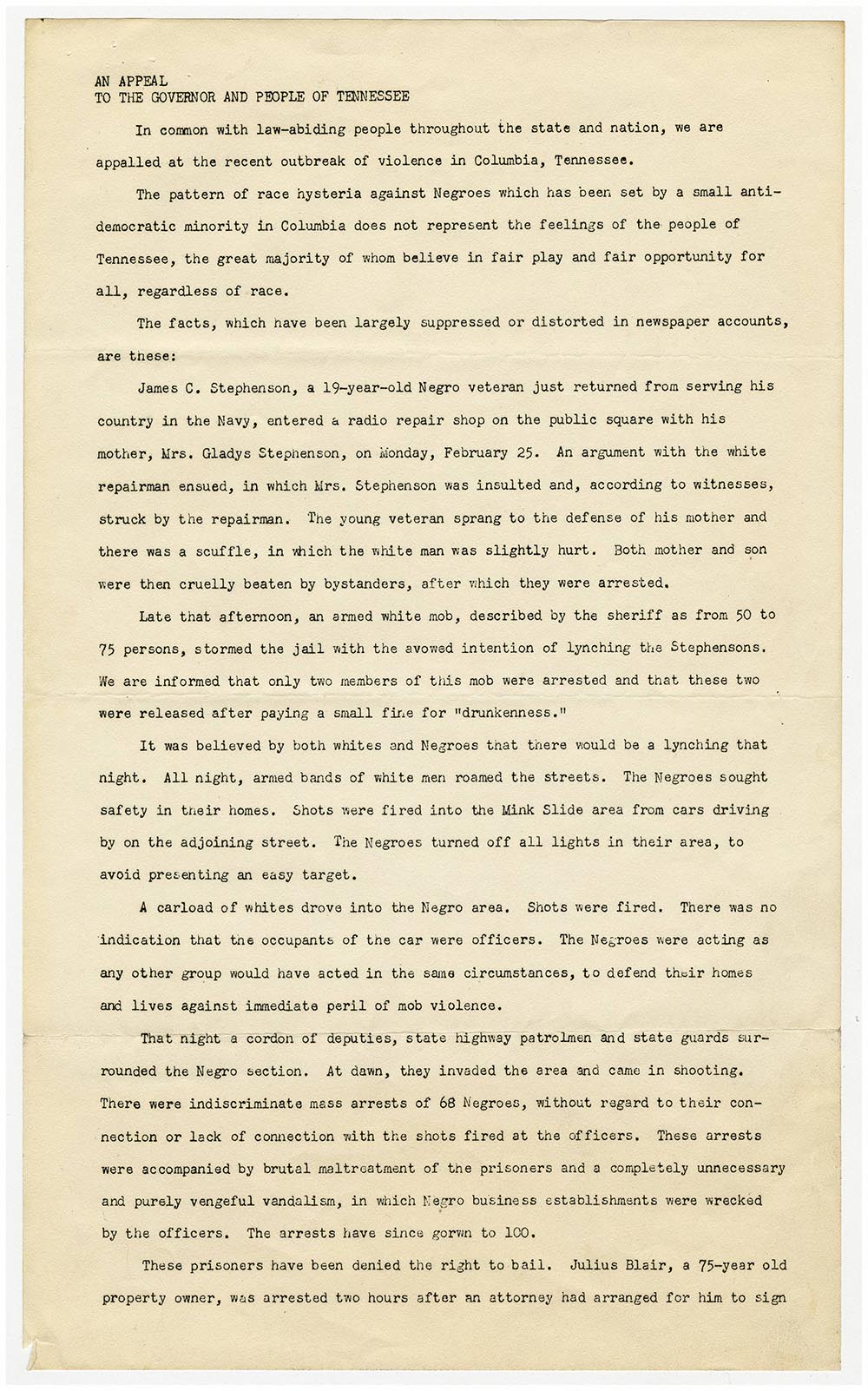

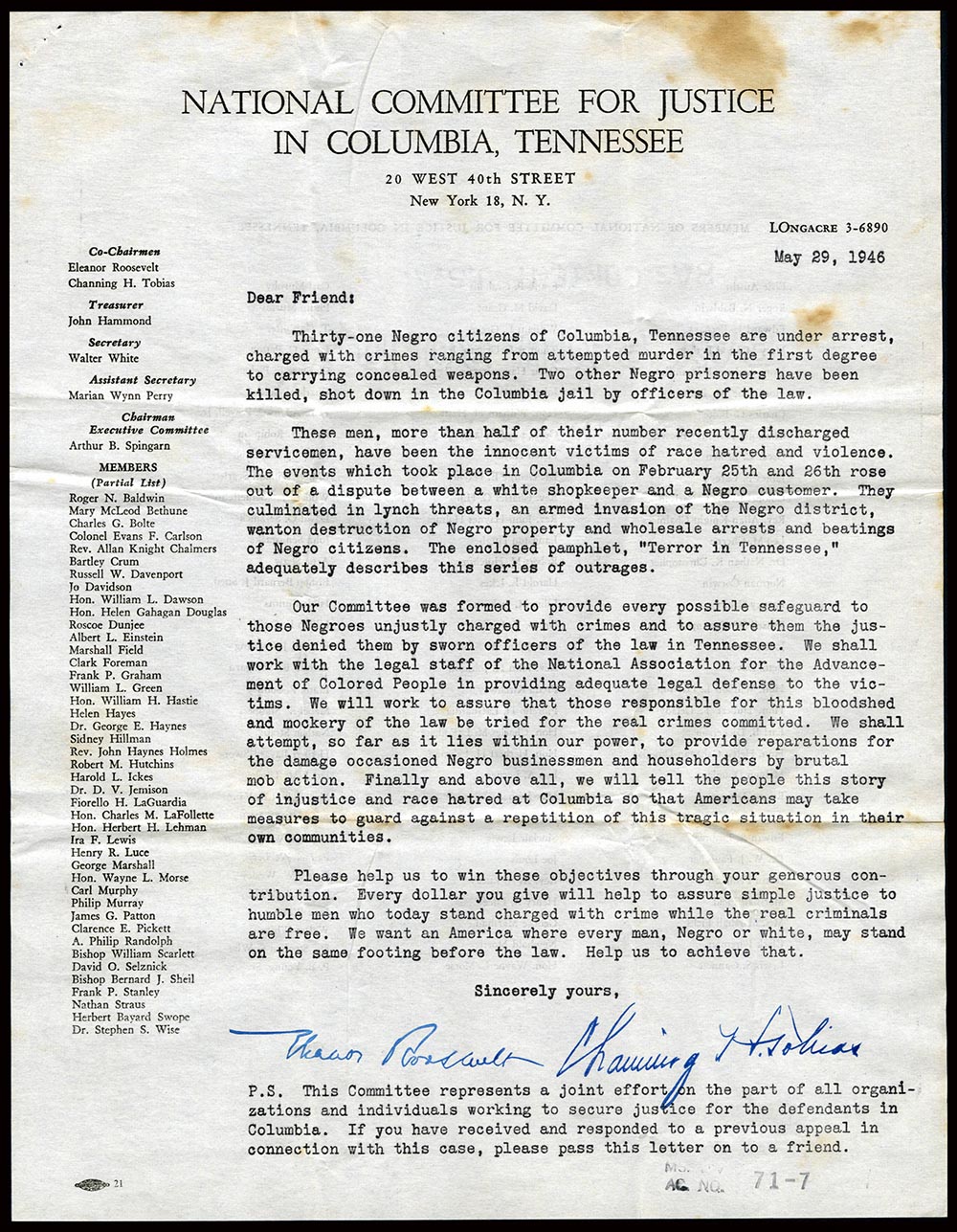

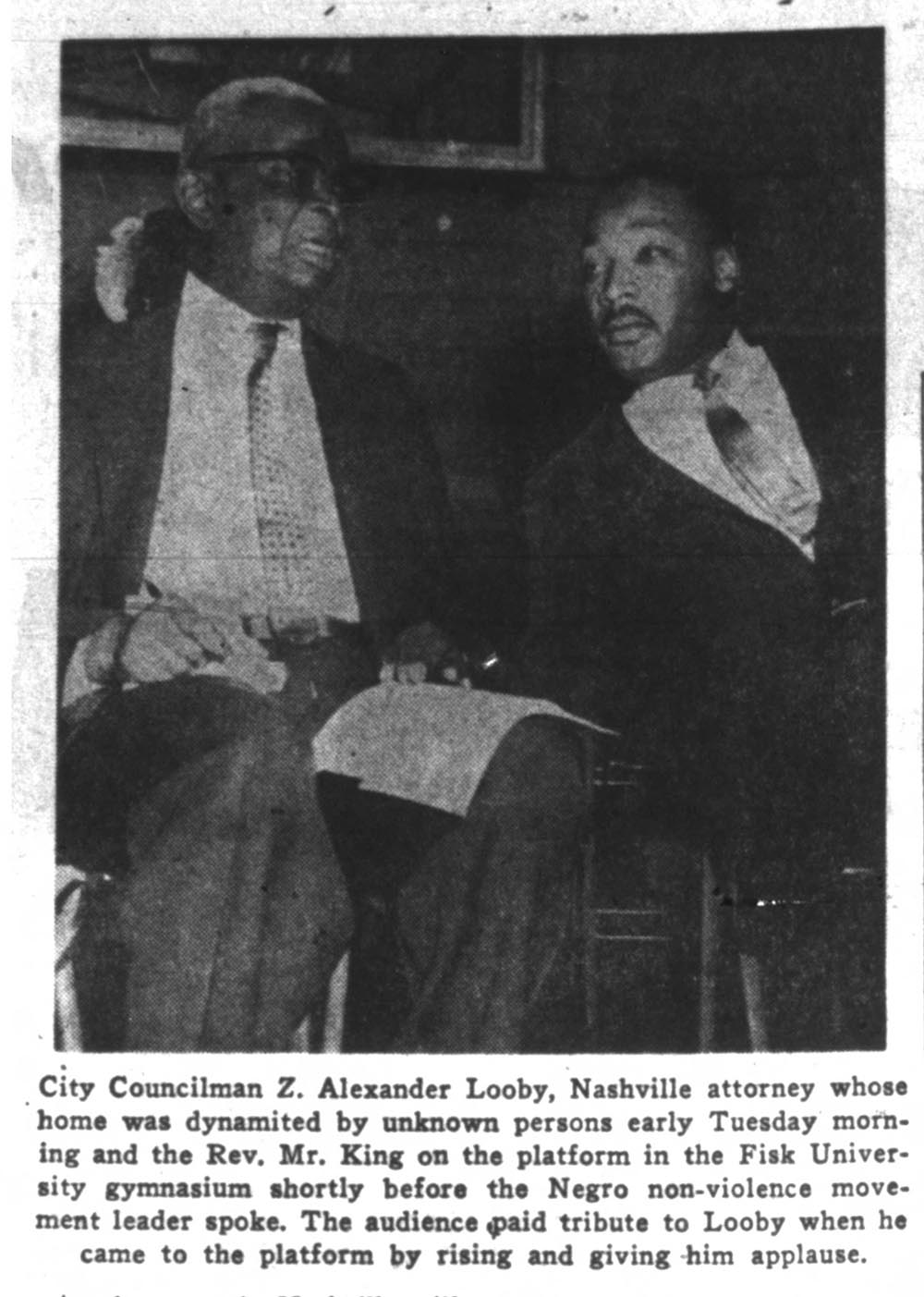

While veterans in Athens were helping overthrow the old political order, newly returned African American veterans in Columbia began a movement for improved civil rights for African Americans. A fight in a downtown Columbia department store in February 1946 set off a rampage by whites through the African American business district. African American veterans were determined to defend their community and themselves against the racial attacks and lynchings that had occurred in the past. Although the State Guardsmen prevented widespread riots, highway patrolmen ransacked homes and businesses, and two African American men taken into custody were killed. Twenty-five African American defendants were accused of encouraging the violence. These men were represented by Nashville attorney Z. Alexander Looby and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) counsel Thurgood Marshall. The men were eventually acquitted of the charges. More importantly, the Columbia Race Riot focused national attention on violence against African American citizens and prompted at least a verbal commitment from the Federal government to protect the civil rights of all Southerners. The aftermath of the Columbia events created a precedent, or example, that organizations like the NAACP could use to push for further government protection of civil rights during the following decade.

The growing assertiveness of African Americans after 1945 was not an accidental development. The sacrifices of African American soldiers during World War II had made discrimination back home less tolerable. Favorable Supreme Court rulings and the willingness of President Roosevelt to reach out to African American leaders had encouraged government protection of civil rights. By 1960, two-thirds of Tennessee’s African American population lived in towns or cities, which made it easier to organize for collective actions such as boycotts or sit-ins. A boycott is a form of protest in which a group refuses to buy goods from certain businesses. A sit-in is a form of protest in which demonstrators refuse to leave a place until their demands are met.

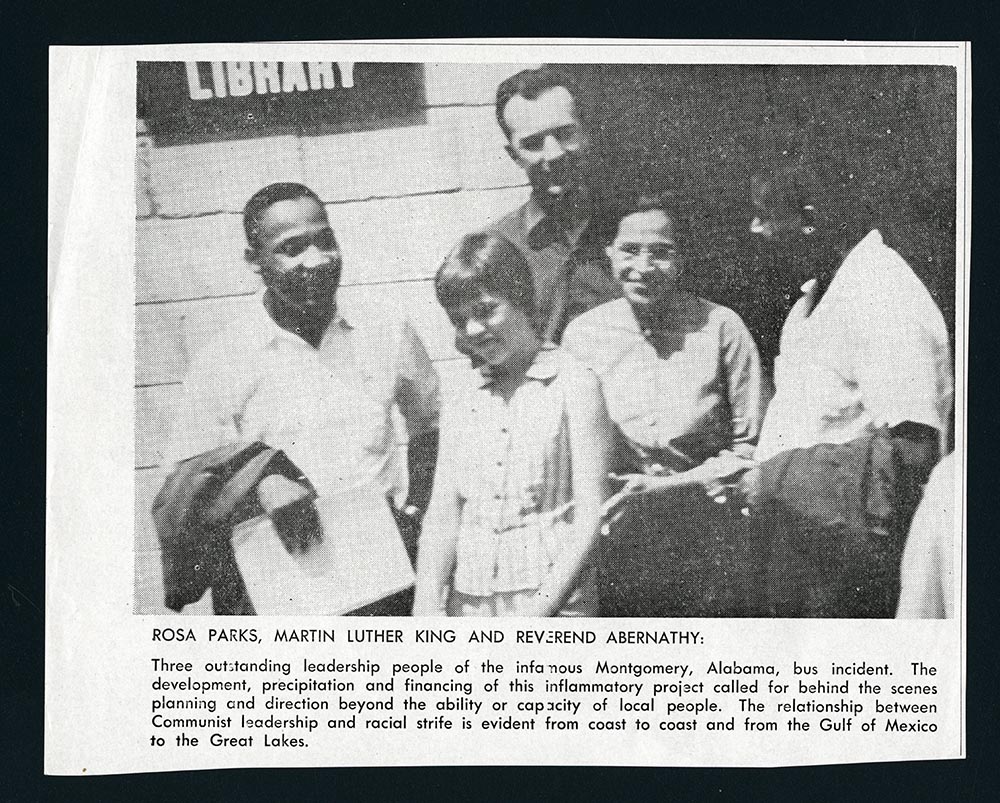

Organization and discipline were nurtured in places like the Highlander Folk School in Grundy County. Founded by Myles Horton and Don West, Highlander became an important training center during the 1950s for community activists and civil rights leaders. The school was shut down by state officials at the height of the desegregation crisis, but it soon reopened to continue its work. Governor Clement was less harsh than other Southern governors in his opposition to the 1954 Supreme Court’s decision on Brown v. Board of Education, which ordered an end to segregated schools. He did not use his office to “block the schoolhouse door,” and he pledged to abide by the law of the land with regard to civil rights.

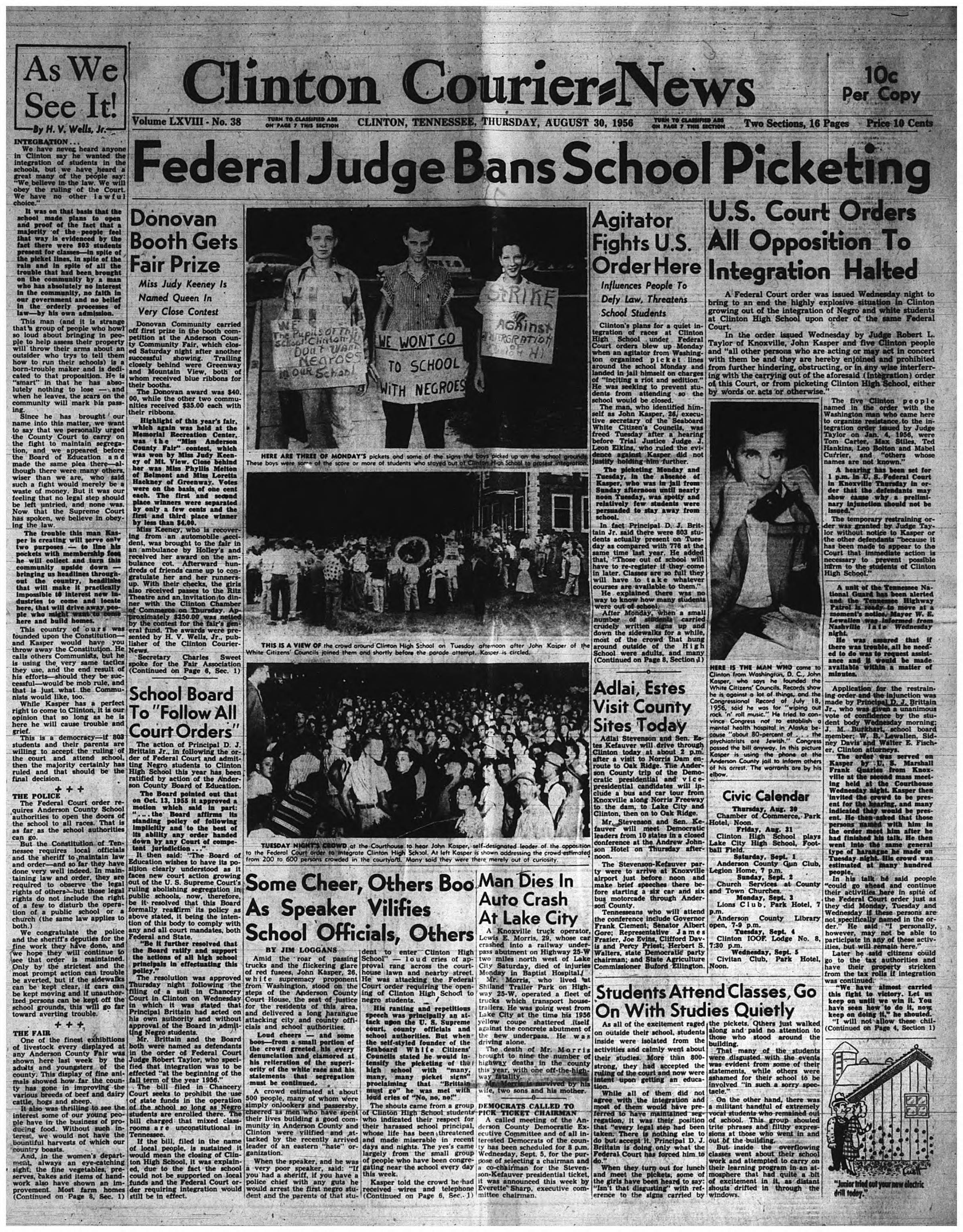

In 1950, four years before the landmark Brown decision, African American parents in Clinton filed suit in Federal district court to give their children the right to attend the local high school instead of being bused to an African American school in Knoxville. Early in 1956, Judge Robert Taylor ordered Clinton to desegregate its schools based on orders from the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to rule in accordance with the Brown decision. Twelve African American students registered for classes that fall, and matters proceeded smoothly until agitators John Kasper of New Jersey and Asa Carter of the Birmingham White Citizens’ Council arrived in Clinton to organize resistance to integration. Governor Clement had to call out 600 National Guardsmen a few days after school opened to defuse the violent atmosphere. The African American teenagers courageously endured months of taunts and threats while attending the school. In May of 1957, Bobby Cain became the first African American to graduate from an integrated public high school in the South. A year and a half later, three bomb blasts ripped apart the Clinton High School building.

In the fall of 1957, Kasper was back in the spotlight, this time in Nashville where the school board planned to integrate first grade in response to lawsuits brought by African American parents. Thirteen African American students registered at five formerly all-white schools, while as many as fifty percent of the white students stayed home. On September 9, Hattie Cotton School, where one African American child was enrolled, was dynamited and partially destroyed. Two years later, the Supreme Court approved Nashville’s grade-a-year integration plan. Memphis and many smaller towns, meanwhile, adopted an even slower pace in desegregating their schools. By 1960, only 169 of Tennessee’s 146,700 African American students attended integrated schools.

From 1960 to 1963, a series of demonstrations took place in Nashville that would have a national impact on the civil rights movement. Nashville’s African American community was uniquely situated to host these historic events due to the concentration of African American leaders in local universities and churches. African American doctors and lawyers also gave considerable support to the demonstrators. Kelly Miller Smith of the First Baptist Church, along with C.T. Vivian and James Lawson, who had studied Ghandi’s tactics of nonviolent resistance, provided leadership and training for young activists who were determined to confront segregation in downtown businesses.

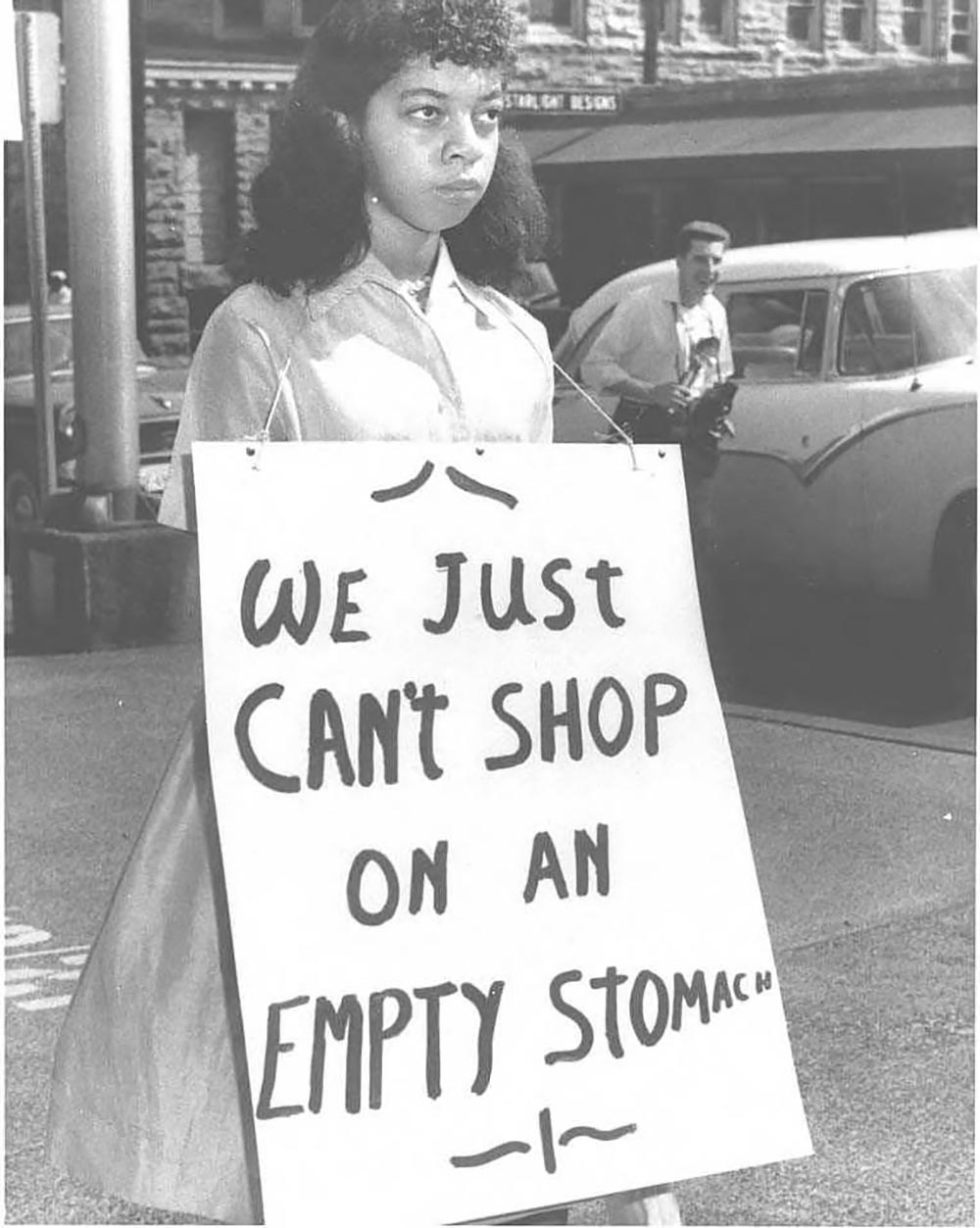

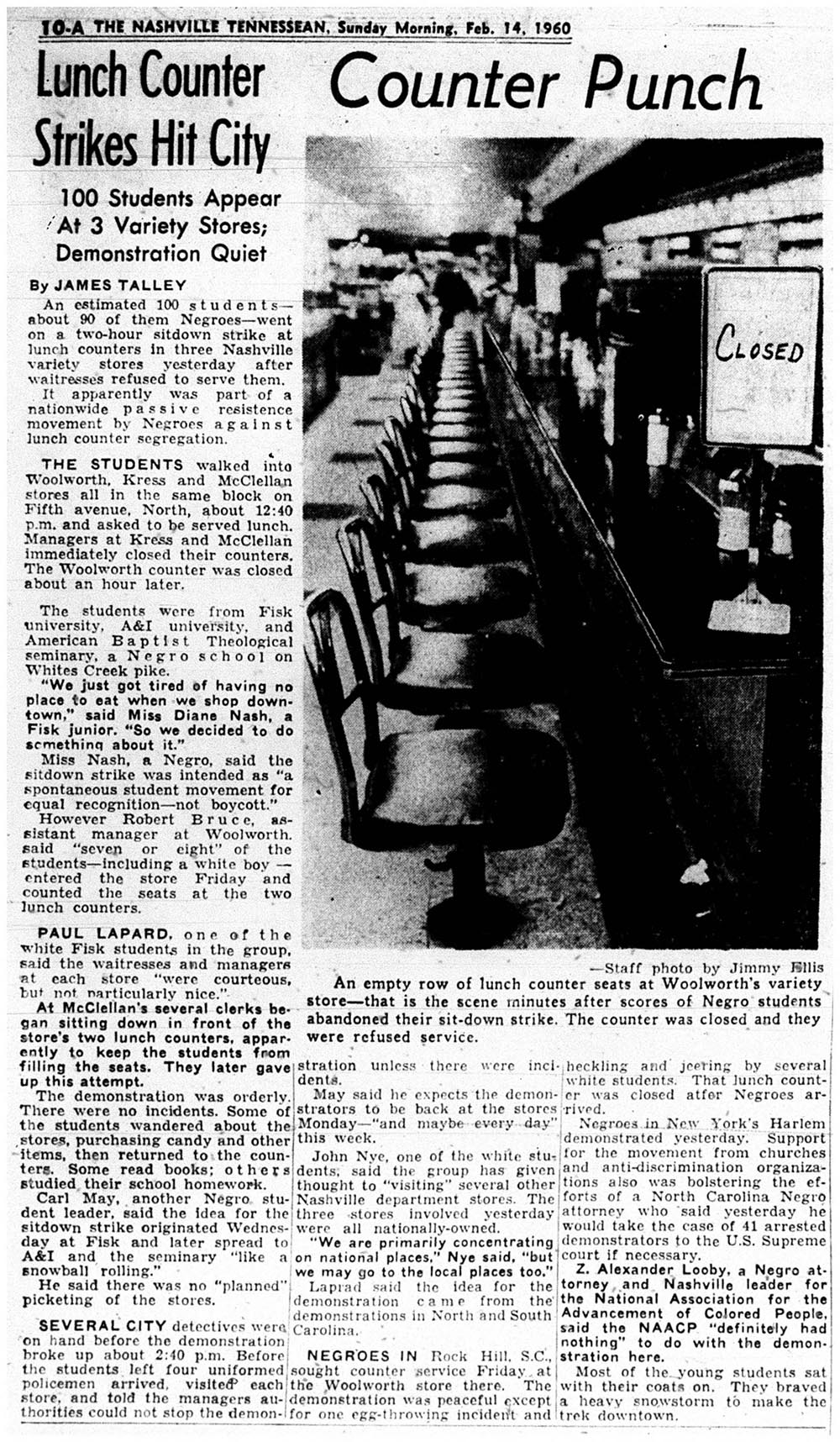

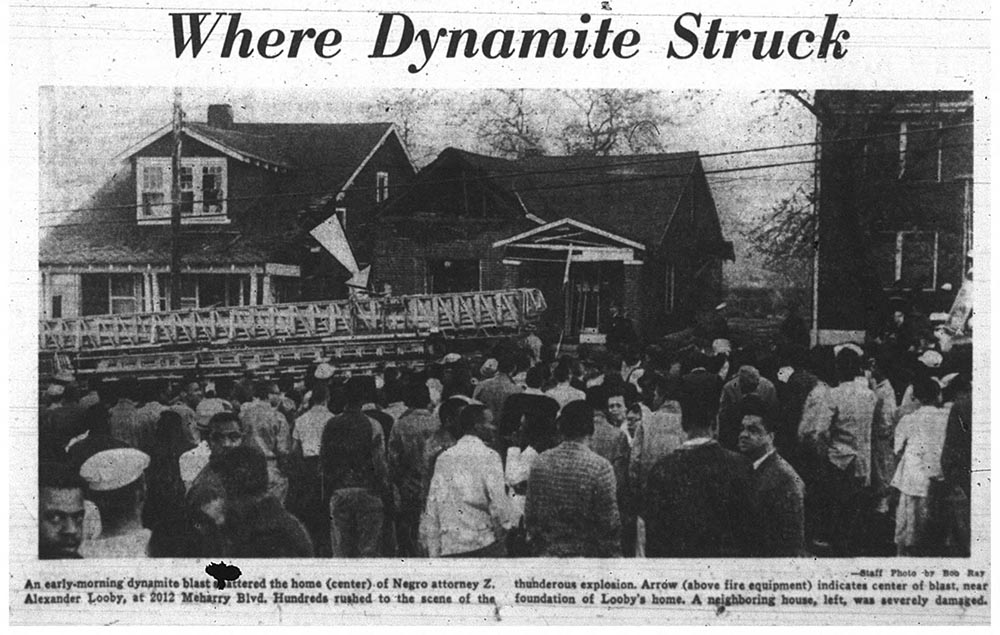

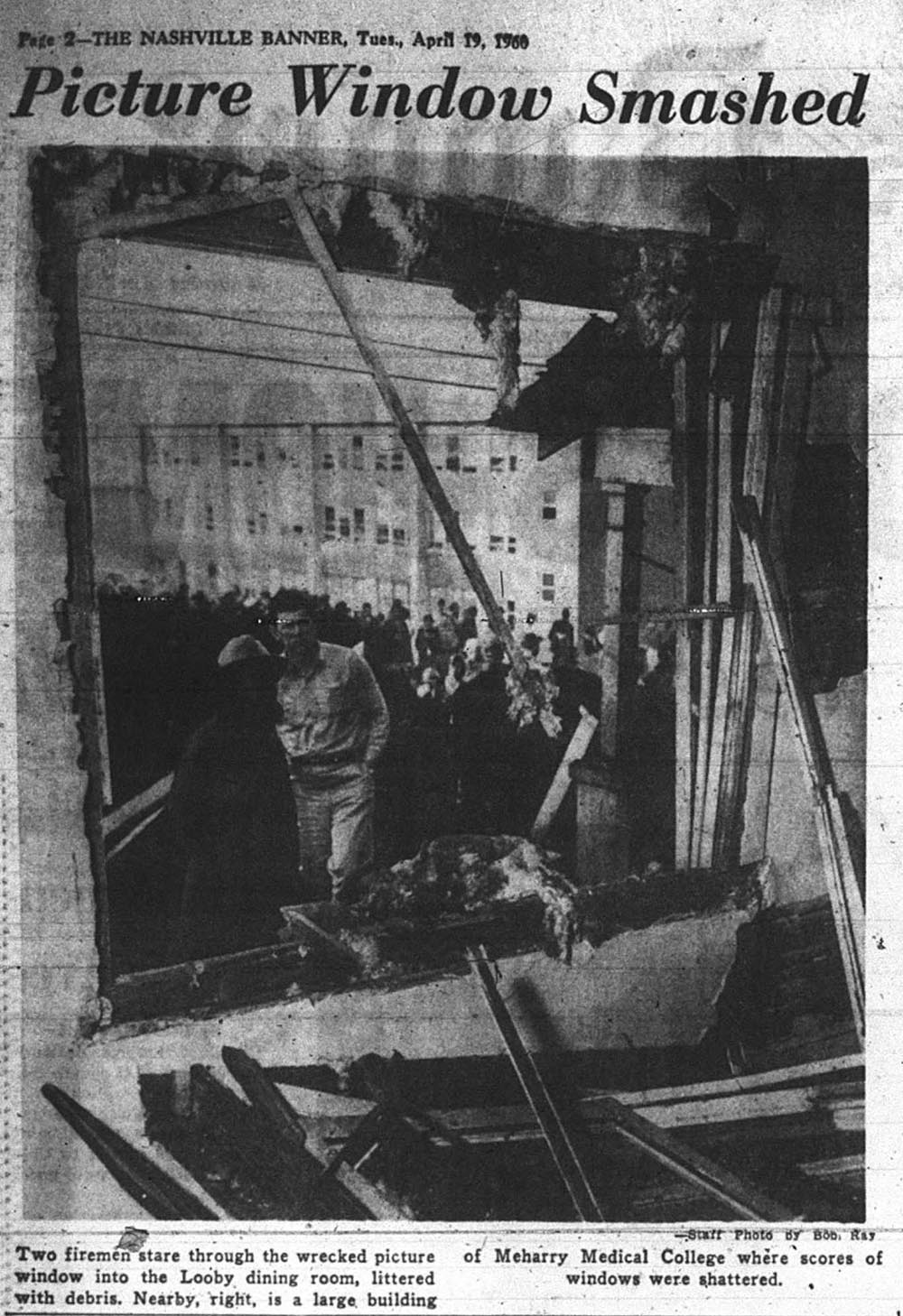

The first Nashville sit-in took place on February 13, 1960. Students from Fisk University, Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University, and the American Baptist Theological Seminary attempted, in peaceful fashion, to be served at whites-only downtown luncheon counters. Two months went by, hundreds of students were arrested, and some were beaten, but still they kept taking their places at the segregated counters. A consumer boycott of downtown stores spread through the African American community and put additional pressure on merchants. On April 19, an early-morning bombing destroyed the home of the students' attorney, Z. Alexander Looby. In response, Fisk University student Diane Nash organized several thousand protesters to silently march to the courthouse to confront city officials. The public was horrified by the violent tactics of the extreme segregationists. The next day, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke to a large audience at Fisk. On May 10, 1960, a handful of downtown stores opened their lunch counters on an integrated basis as Nashville became the first major city in the South to begin desegregating its public facilities. The Nashville sit-in movement and the students’ disciplined use of nonviolent tactics served as a model for future action against segregation.

Activists in several Tennessee cities kept the pressure on restaurants, hotels, and transportation facilities that refused to drop the color barrier. High school and college students in Nashville were instrumental in organizing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which trained many civil rights leaders during the 1960s. Diane Nash was one of the few women to hold a leadership position within civil rights organizations such as SNCC. Tennesseans participated in the Freedom Rides, in which groups of black and white passengers tried to integrate bus terminals across the South.

In 1965, A. W. Willis, Jr., of Memphis became the first African American representative elected to the General Assembly in sixty-five years. From 1959 to 1963, the struggle for voting rights centered on rural Fayette County, where 700 African American tenant families were forced off the land when they tried to register to vote. Community activists, such as Viola and John McFerren, helped organize a “tent city” where evicted tenants were fed and sheltered despite harassment and a trade ban by local white merchants. In 1968, Memphis sanitation workers broadened the struggle by going on strike against discriminatory pay and work rules. In support of the strike, Dr. King came to Memphis, and on April 4, he was assassinated by a sniper as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. The 1960s thus ended on an ominous note, with historic strides having been made in race relations, but with much yet to be done.

The end of the Clement-Ellington era saw the demise of single-party domination in Tennessee politics. Beginning in 1966 with Howard Baker’s election to the U.S. Senate, Tennesseans turned increasingly toward the Republican Party. Between 1968 and 1972, Tennessee voted for Richard Nixon twice and elected Winfield Dunn—the first Republican governor since 1921—and two Republican senators, Baker and William Brock. The Watergate scandal temporarily halted this trend. In the mid-1970s, Democrat Ray Blanton defeated Maryville attorney Lamar Alexander for governor, James Sasser won a Republican-held Senate seat, and Jimmy Carter carried the state’s vote for President. Howard Baker became a leader in the Senate and was eventually named White House Chief of Staff in the Reagan White House. In 1978, Alexander won the governor’s race; he then took office early because of questionable acts by the outgoing Blanton administration.

State government services had grown significantly since the New Deal and World War II, but particularly since the passage of the first sales tax in 1947. Governor McCord’s two percent tax, initially passed for schools and teachers, was raised to three percent in 1955. By the late 1950s, sales tax revenue had become the chief means of financing state government. In order to fund Governor Alexander’s school reform package in 1985, the Legislature raised the state sales tax to 5.5 percent. Local governments had the option to add to this percentage making Tennessee’s sales tax one of the highest in the nation.

In the late twentieth century, Tennessee carried on its long tradition of military service. From 1950 to 1953, more than 10,500 Tennesseans served in the Korean War, with 843 losing their lives in combat. The long Vietnam War of the 1960s and early 1970s cost 1,289 Tennessee lives and caused student unrest on campuses across the state. One outstanding participant was Navy Captain (and later Vice Admiral) William P. Lawrence of Nashville, who was shot down over North Vietnam in 1967. Captain Lawrence was held captive for six years and spent part of the time in solitary confinement. Captain Lawrence’s reflections on his native state produced what the Legislature adopted as the state’s official poem shortly after his return.

The Persian Gulf War of 1990–1991 generated considerable excitement and support, as Tennesseans rallied around the twenty-four units mobilized for Operation Desert Storm at the Fort Campbell Army Base. More recently, Tennesseans have made major contributions to the Global War on Terror. In addition to thousands of regular army personnel, more than 14,000 Tennessee soldiers, sailors, and airmen (more than eighty-four percent of the entire Tennessee National Guard) have deployed to the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. As of October 2017, 148 Tennesseans in service of our nation have given their lives in the War on Terror.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, Tennessee has enjoyed a period of business expansion and growth. In 1980, Nissan Corporation of Tokyo announced plans to build the largest truck assembly plant in the world in Smyrna. Nissan’s American corporate headquarters is now located in Williamson County. By 1994, sixty-nine Japanese manufacturers with investments in excess of $4 billion and more than 27,000 employees had established operations in Tennessee. Tennessee also landed the General Motors plant; construction on the $2.1 billion facility near Spring Hill was completed in 1987. Volkswagen announced in 2008 that it was building a major automobile production facility in Chattanooga, and the first automobiles rolled out of the factory in 2011. In January of 2019, Volkswagen announced that it was investing $800 million to build a new assembly line at its Chattanooga plan to build electric SUVs. The project is expected to create up to 1,000 new jobs at the plan and the first electric vehicles are expected to be produced in 2022.

Over the years, Tennesseans have made significant contributions to science. Two members of the Vanderbilt University faculty, Earl Sutherland in 1971 and Stanley Cohen in 1987, won Nobel Prizes for their pioneering medical research. In 1985, Dr. Margaret Rhea Seddon became the first Tennessean in space, eventually flying on three Space Shuttle missions. Edgar Bright Wilson, Jr., who was born in Gallatin, received the National Medal of Science in 1975 for his contributions to a field of chemistry called molecular spectroscopy. Astronaut William Shepherd from Oak Ridge, served as Commander of Expedition 1, the first crew on the International Space Station. As a result of his service as an astronaut, Shepherd received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 2003. In 2008, former vice president Albert Gore, Jr., was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on global warming.

Tennessee has also produced a number of distinguished figures in literature. Robert Penn Warren, who lived in Clarksville and attended Vanderbilt University, received the 1947 Pulitzer Prize for his novel All The King's Men. Warren also won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1958 and 1979. James Agee, an American novelist and poet, won the 1958 Pulitzer Prize for his autobiographical novel, A Death in the Family. In 1977, Alex Haley of Henning was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Roots, the most successful book ever written by a Tennessean and one largely responsible for reviving popular interest in family history.

Tennessee has also been an important place for producing a variety of music and performers. Few Americans have ever matched the personal popularity of the “King of Rock ’n’ Roll,” Elvis Presley whose recordings for Memphis’s Sun Records Studio in the mid-1950s launched a new era in popular music.

The classic rock 'n' roll music of Elvis and his fellow performers at Sun Records as well as the rhythm-and-blues "Memphis sound" represented by Stax Records, have achieved wordwide renown. Elvis's home, Graceland, is the most visited celebrity museum in the country.

Similarly, Dolly Parton from Sevier County has become an icon in popular culture. As a country music performer, Dolly has earned nine Grammy Awards, ten Country Music Association Awards, and seven Academy of Country Music Awards. In 2005, Dolly was honored with the National Medal of Arts, the highest honor given by the U.S. government for excellence in the arts. One year later, in 2006, Dolly received the Kennedy Center Honor for her contributions to the arts. In 1990, Dolly started Dolly Parton's Imagination Library. A book gifting program that mails free, high quality books to children from birth until they begin school, the Imagination Library has given away over 129 million books in the US, Canada, the UK, and Australia.

While Dolly Parton has had a major impact on the music industry, other Tennesseans have also made significant contributions. Singer and songwriter Tina Turner, from Nutbush, has won twelve Grammy Awards and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991. She was also a recipient of the Kennedy Center Honor in 2005. Memphis native Justin Timberlake, has had many chart topping songs, and has won ten Grammy Awards and nine Billboard Music Awards.

A new generation of Tennessee public servants rose to importance during the 1980s and 1990s. Women carved out a more prominent role, with Jane Eskind becoming the first woman to be elected to statewide political office as Public Service Commissioner in 1986. Martha Craig Daughtrey became the first woman on the Tennessee Supreme Court. Albert Gore, Jr.’s, 1976 election to the U.S. House of Representatives began a political career that would carry him to the vice presidency of the United States in 1992 and a run for the presidency in 2000. Gore lost that election by a handful of electoral votes and failed to carry his home state, although he won a majority of the nation’s popular vote. In 1982, Lamar Alexander won his second term as governor, becoming the first executive to serve consecutive four-year terms. His “Better Schools” program was one of the earliest and most significant attempts at fundamental school reform in the country. As a result of the program, Alexander was appointed by President Bush as Secretary of Education in 1990.

Sports have long been a popular entertainment and source of pride for Tennesseans. In 1960, Wilma Rudolph from St. Bethlehem (near Clarksville) became the first American woman to win three gold medals in track and field at a single Olympics. The University of Tennessee’s Lady Vols, under Coach Pat Head Summitt, set the standard of excellence for women’s collegiate basketball by winning eight national championships between 1987 and 2008. The football team of the University of Tennessee reached the peak of college football in 1998 by going undefeated and being crowned National Champions. In 2014 and 2019, Vanderbilt University’s men’s baseball team won the NCAA Championship.

Professional sports have come to Tennessee in a big way, with the NBA’s Memphis Grizzlies, the NHL’s Nashville Predators, and the NFL’s Tennessee Titans. The Titans went to the Super Bowl and two AFC Championships between 1998 and 2003, during which time they were the winningest team in the NFL. The Nashville Predators are also notable playoff contenders in the NHL. In 2017, the hockey team made headlines with a historic run through the Stanley Cup Playoffs before being edged out in the finals. The Predators continued their success in 2018 when they clinched the first division title in team history. They also acquired their first Presidents' Trophy in 2018. Tennessee gained another major professional sports team in 2020 with an expansion team from Major League Soccer (MLS) known as the Nashville Soccer Club. A new 30,000-seat stadium specifically for the soccer team was constructed at the Nashville Fairgrounds.

In recent years, Tennessee has seen the construction of new cultural institutions to preserve and promote its treasured history. In October of 2018, a new Tennessee State Museum opened in Nashville near Bicentennial Mall State Park. In addition to a new State Museum, the National Museum of African American Music in Nashville held its grand opening on January 18, 2021. A new Tennessee State Library & Archives (TSLA) opened on April 13, 2021. The new 165,000-square-foot facility includes a climate-controlled chamber for storing historic books and manuscripts with a space-saving robotic retrieval system.

One of the most dominant news headlines during the year of 2020 was the global pandemic caused by a respiratory virus known as Covid-19. The highly contagious virus swept the globe and impacted the lives of people worldwide. To prevent the spread of the virus, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) provided safety guidelines such as recommending people wear masks, social distance at least six feet from one another, avoid large crowds, and wash their hands. In Tennessee and throughout the world, many schools and universities turned to virtual learning, while some businesses and other institutions began to work remotely. The pandemic forced many restaurants, businesses, theaters, tourist sites, and sports venues to close temporarily. Many Tennesseans as well as other Americans contracted the virus. As a result, many had medical complications, and some died.

Tennesseans draw great strength from their heritage, not only of great deeds and events, but of the more enduring legacy of community ties and respect for tradition. One does not have to look hard for Tennessee’s significance in American history. The state played a key role in expanding the first frontier west of the Appalachian Mountains and provided the young nation with much of its political and military leadership, including the dominant figure of Andrew Jackson. Divided in loyalties and occupied for much of the Civil War, Tennessee was the main battleground in the western theater of that conflict. The early twentieth century witnessed clashes over cultural issues such as prohibition, women’s suffrage, and school reform. World War II accelerated the changeover from an agricultural to an industrial and predominantly urban state. As older cultural byways fade, Tennessee has become home to some of the most advanced sectors of American business and technology. Our state’s mix of forward-looking innovation, great natural beauty, and a people solidly grounded in tradition and community has proven an irresistible allure for the rest of the country.