The new state of Tennessee began to grow quickly once the threat of war with Native Americans declined. After 1806, the state began to sell public land for low prices, which attracted settlers from the East. Between 1798 and 1806, the Cherokee and Chickasaw signed a number of treaties in which they ceded large areas of land. The state gained much of the south-central region and most of the Cumberland Plateau. This was especially important because it gave the state control over all the land from the eastern counties to the Cumberland Settlements. It also made it easier for travelers to reach the Cumberland Settlements.

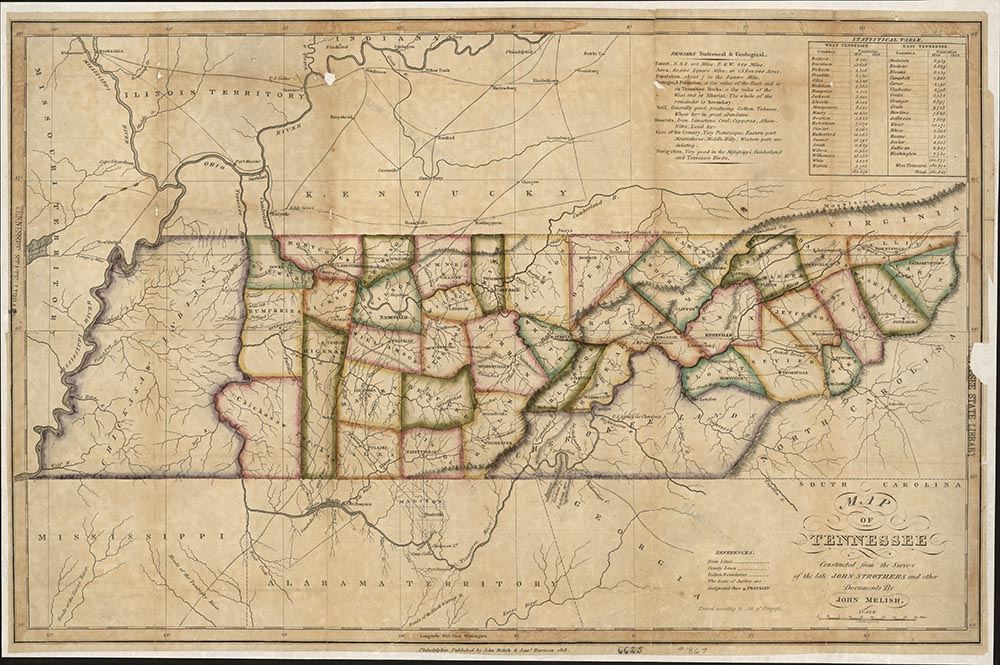

The availability of so much land, some of which was very fertile, caused Tennessee’s population to grow very rapidly. Between 1790 and 1800, the state’s population tripled. It grew 250 percent from the years 1800 to 1810, increasing from 85,000 to 250,000 during the first fourteen years of statehood alone. By 1810, Middle Tennessee had moved ahead of the eastern section in population. This shift in population led to a shift in political power from the older region of East Tennessee to the middle section of the state. The state capital was Knoxville from 1796 to September 1807, when the capital was Kingston for a day. The capital was relocated back to Knoxville until 1812, moved to Nashville from 1812 to 1817, then returned briefly to Knoxville. From 1818 to 1826, the General Assembly met in Murfreesboro, and in 1826, the capital moved to its permanent site in Nashville.

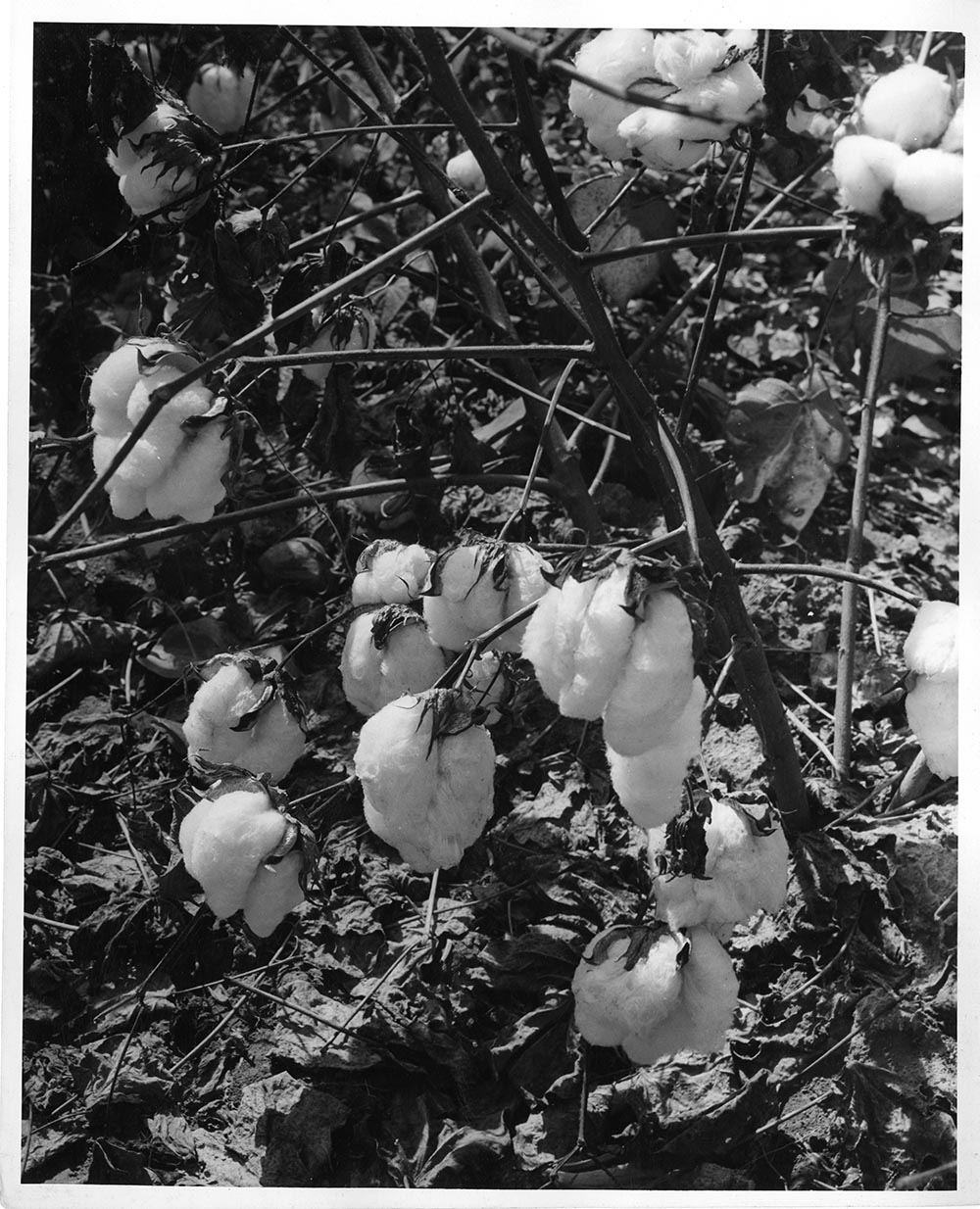

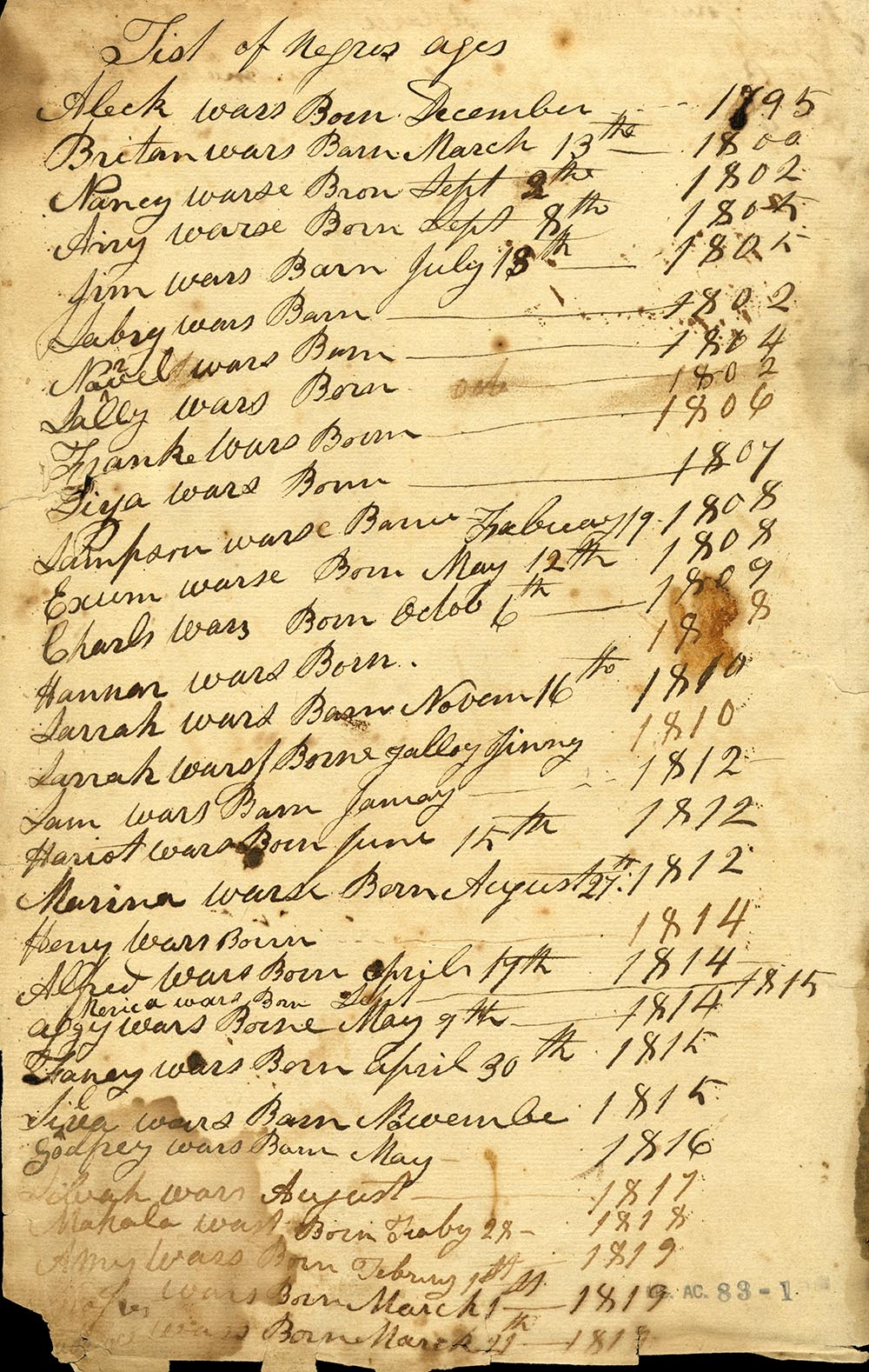

Slavery played a major role in Tennessee’s rapid expansion. The territorial census of 1791 showed an African American population of 3,417—ten percent of the general population. By 1800, the African American population had jumped to 13,584 (12.8 percent), and by 1810, African Americans made up more than twenty percent of Tennessee’s people. Most African Americans in Tennessee were slaves. More slaves were brought to the state following the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793. Cotton and tobacco grew well in the fertile soil of Middle and West Tennessee but required intensive labor, or work, to produce. As a result, slavery was more common in Middle and West Tennessee than mountainous East Tennessee. By 1830, there were seven times as many slaves west of the Cumberland Plateau as in East Tennessee.

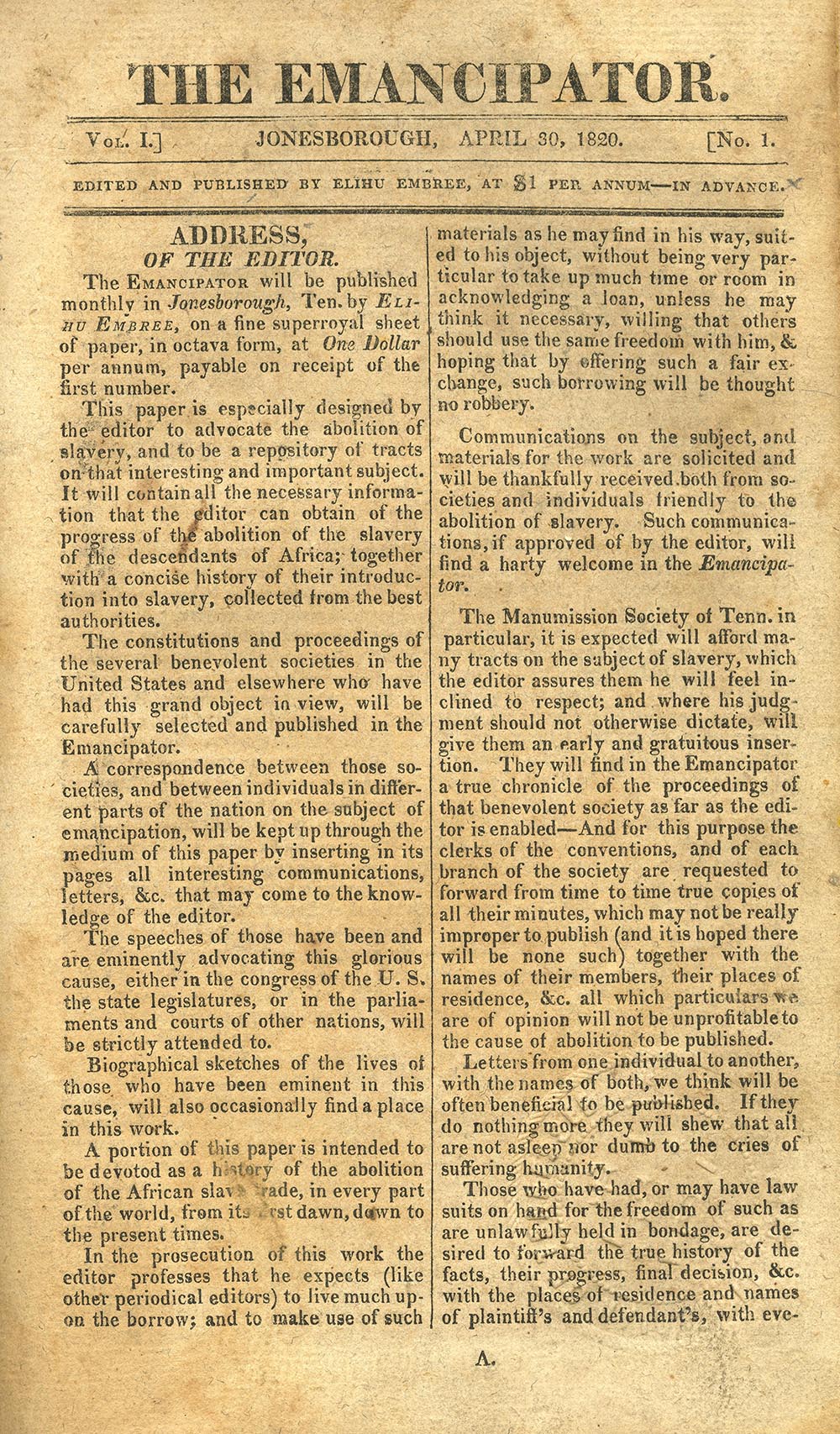

In addition to slaves, Tennessee had a fairly large population of free African Americans. The 1796 Constitution had granted suffrage, or voting rights, and relative social equality to free African Americans. The 1796 Constitution also made it easy for owners to manumit, or free, their slaves. As slavery became more and more important to Tennessee’s economy, the laws changed. It became more difficult for owners to free their slaves, and free African Americans lost many rights. Some Tennesseans opposed the expansion of slavery, especially in East Tennessee where an emancipation movement developed. Emancipation is an action taken by the government to free slaves. In 1819, Elihu Embree established the first newspaper in the United States devoted entirely to freeing slaves at Jonesborough. The newspaper was originally called the Manumission Intelligencer, but the name was later changed to the Emancipator. By the 1820s, East Tennessee had become a center of abolitionism. Abolition is the desire to abolish or end slavery. East Tennessee was a staging ground for the issue that would divide not only the state but the nation.

Tennessee prospered and developed rapidly between 1806 and 1819. Thirty-six of Tennessee’s ninety-five counties were formed between 1796 and 1819. Isolated settlements developed quickly into busy county seats. A county seat is the town from which the county’s government operates. Nashville, no longer under constant threat of attack, became one of the leading cities of the Upper South.

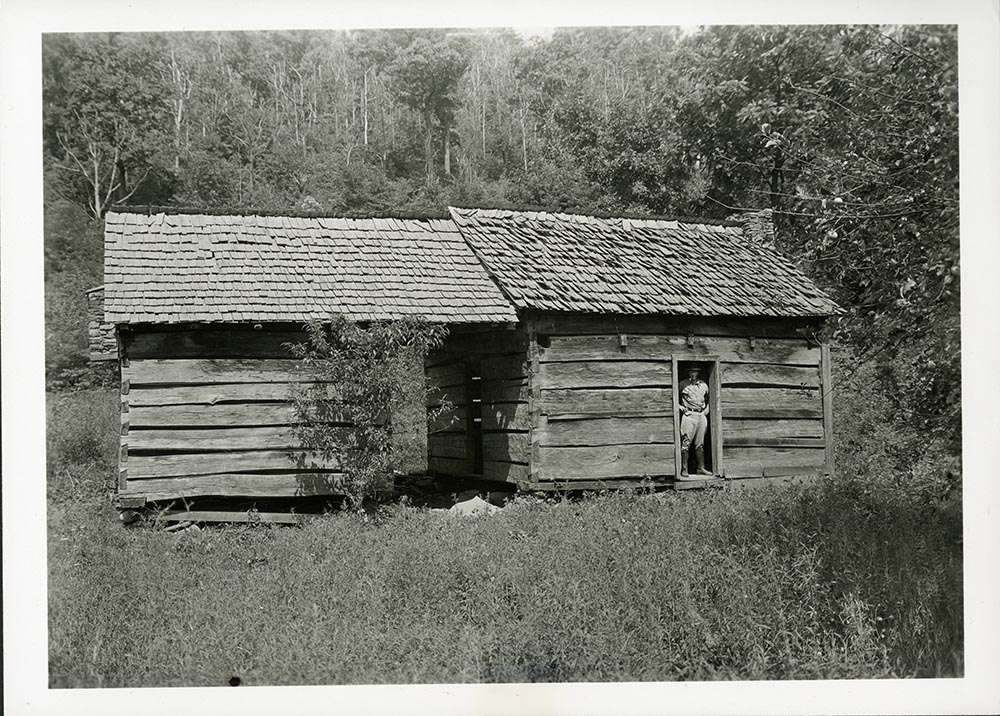

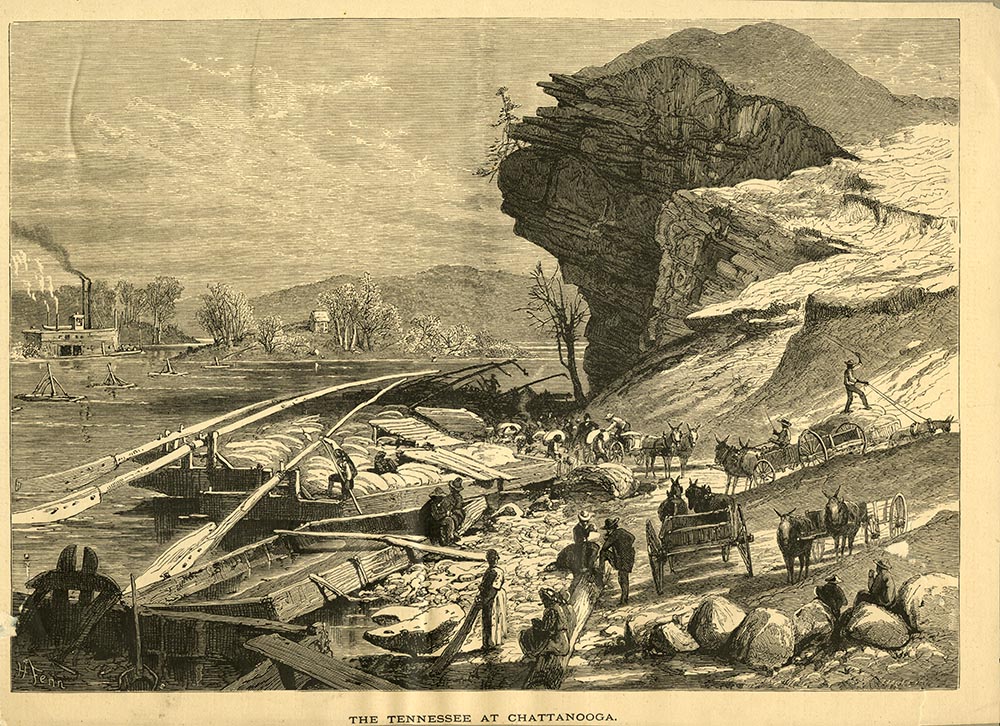

Despite the growth of towns, Tennessee remained mostly rural. Log cabins remained the most common type of housing. Eighty percent of Tennesseans were farmers, and most worked simply to supply the food needs of their families. However, income could be made from selling certain “cash crops.” Cotton and tobacco were cash crops from the beginning. They were profitable, easily transported, and could be worked on plantations, or large farms, with slave labor. Tennessee farmers also converted corn, the state’s most important crop, into cornmeal and whiskey. They also fed corn to hogs which were then butchered to produce cured pork. Because of poor roads, Tennesseans relied mainly on rivers to move their crops to market. Products were shipped by keelboat or flatboat to Natchez and New Orleans on the Mississippi River.

Most types of manufacturing, like spinning cloth, soap-making, and forging tools, were done in the farm household. Household chores were mostly divided by gender. Women were generally responsible for preserving food, cooking, producing cloth and clothing, and caring for children. Men cleared fields, planted crops, forged tools, and cared for animal herds. Children performed many chores such as gathering eggs, milking cows, and working alongside their parents. Some families ran businesses to process farm products. Grist mills ground corn and wheat into meal and flour. Sawmills cut lumber, and tanneries processed animal hides. Distilleries turned corn into whiskey. The one true industry in early Tennessee was ironmaking. Frontier ironworks were constructed in upper East Tennessee by men who had immigrated from Pennsylvania. James Robertson built the first ironworks, called the Cumberland Furnace, in Middle Tennessee in 1796. Soon Middle Tennessee ironmasters built many furnaces and forges to take advantage of the abundant iron ores of the western Highland Rim region. These were complicated enterprises that used both slaves and freemen to dig the ore, cut the wood for charcoal, and operate the furnace. The early Tennessee iron industry supplied blacksmiths, mill owners, and farmers with the metal they needed and laid the groundwork for future industrial development.

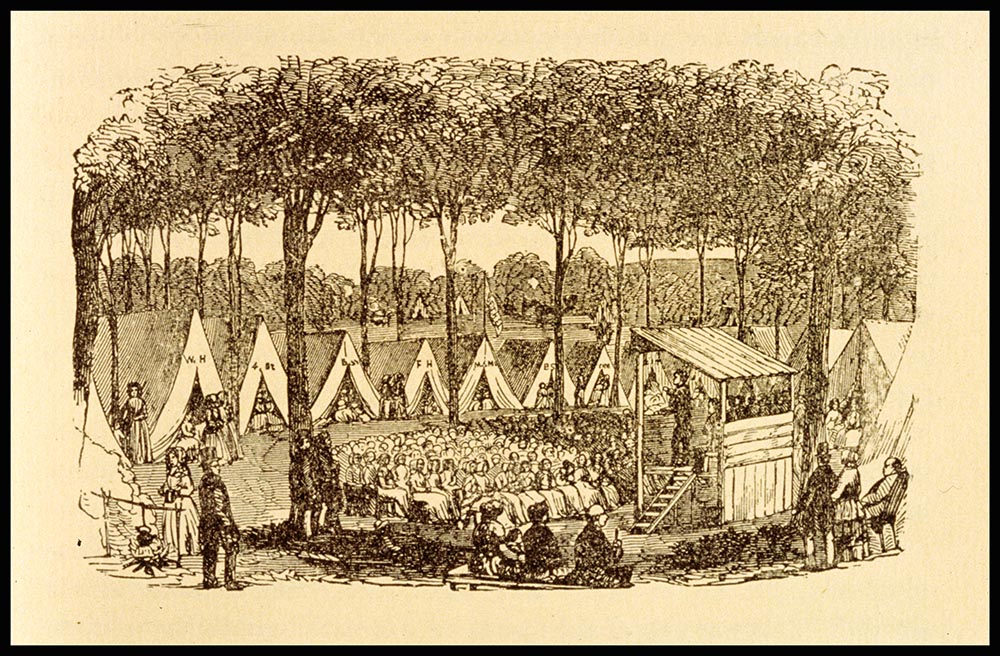

The hardworking settlers had little time for recreation. As a result, the settlers found ways to combine work and recreation. All able-bodied men were required to serve in the militia. The days when the militia mustered, or gathered for duty, served as festive social occasions for the whole county. There was little opportunity for organized religious services in the early days and few ministers to preach. Instead, itinerant, or traveling, ministers held camp meetings. Because travel was so difficult, frontier families would camp near the meeting site for several days. The Methodists and Baptists gained many converts through the camp meetings. Because many of Tennessee’s early settlers were Scots-Irish, Presbyterianism was also very popular. Presbyterianism insisted on an educated clergy, which led to the development of many schools in early Tennessee. Ministers such as Reverend Samuel Doak in East Tennessee and Reverend Thomas Craighead in Middle Tennessee founded academies in the 1790s. Academies chartered by the state were supposed to receive part of the proceeds from the sale of state lands, but this rarely happened. While state support for education languished, ministers and private teachers took the lead in setting up schools across the state.

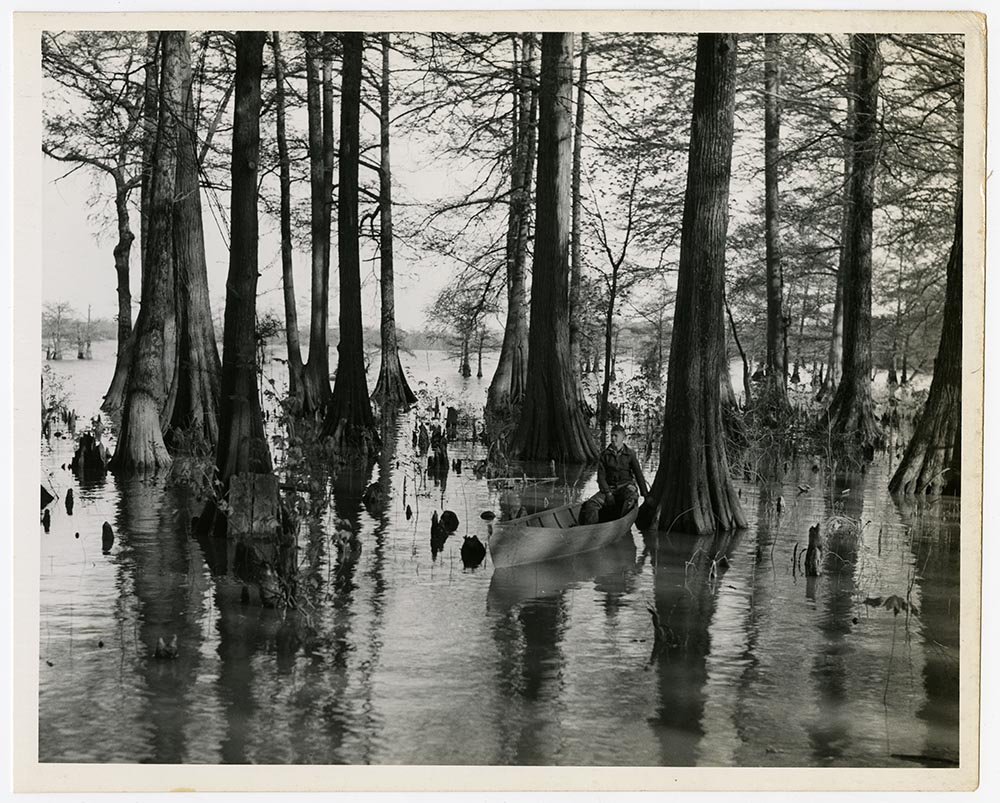

Relations between whites and Native Americans were relatively peaceful after 1794, although trespassing on Indian land was common, and life continued to be hazardous for settlers in remote areas. However, as Tennesseans pushed west and south toward the Tennessee River, they began to press upon Creek territory, and fighting resumed. The Creeks were the most formidable tribe on the Tennessee borders, and they were widely believed to be under the influence of hostile British and Spanish agents. In 1812, Tecumseh and his brother, the Prophet, succeeded in creating a confederacy, or alliance, of tribes in the Ohio Valley. Tecumseh wanted to roll back white settlement. Tecumseh visited the Creek Nation in 1811 to urge the southern tribesmen to join his movement. His prophecy that the earth would tremble as a sign of the coming struggle was seemingly confirmed by a series of massive earthquakes in 1811–1812. The New Madrid Earthquakes caused the Mississippi River to run backwards for a time and resulted in the creation of Reelfoot Lake.

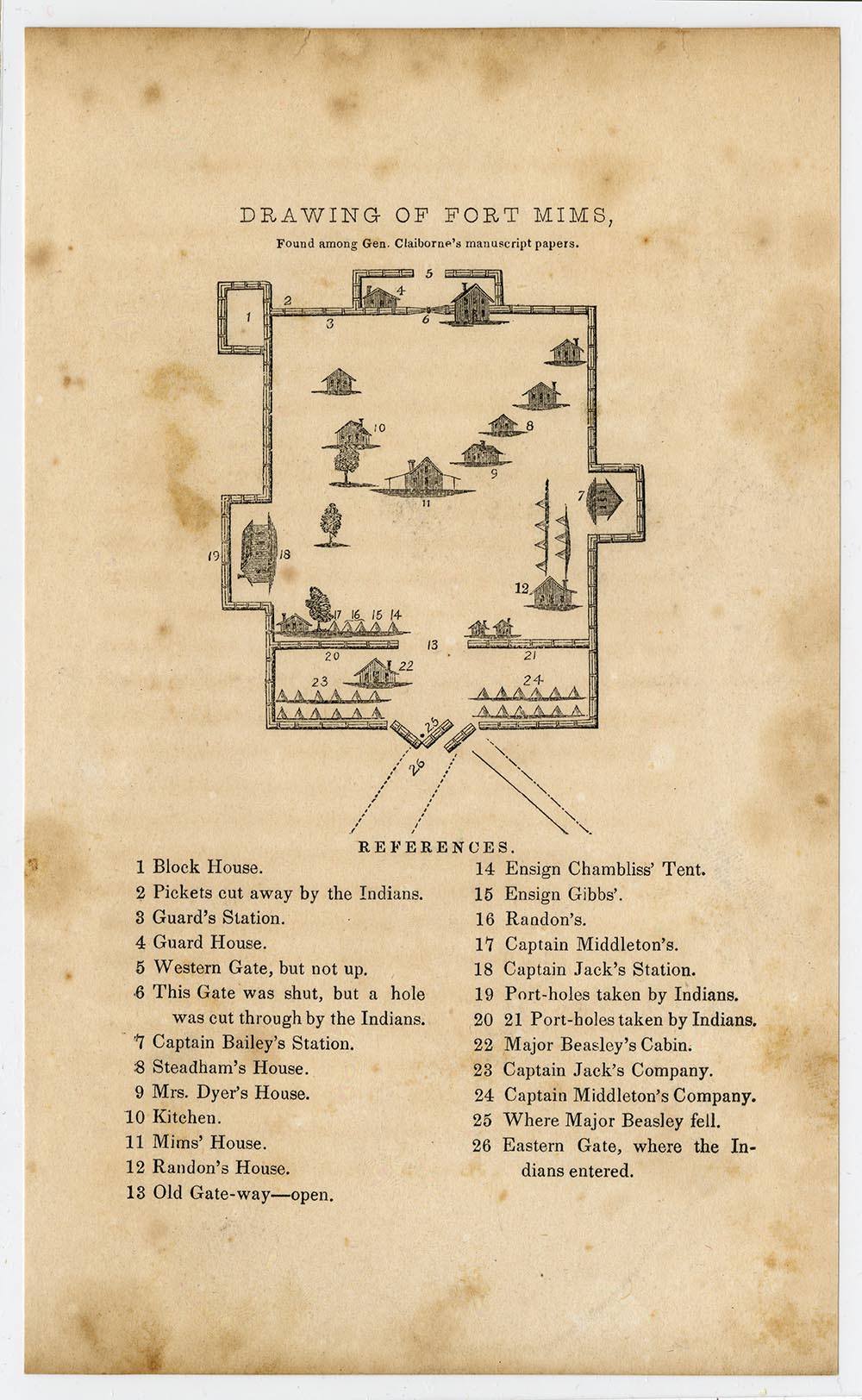

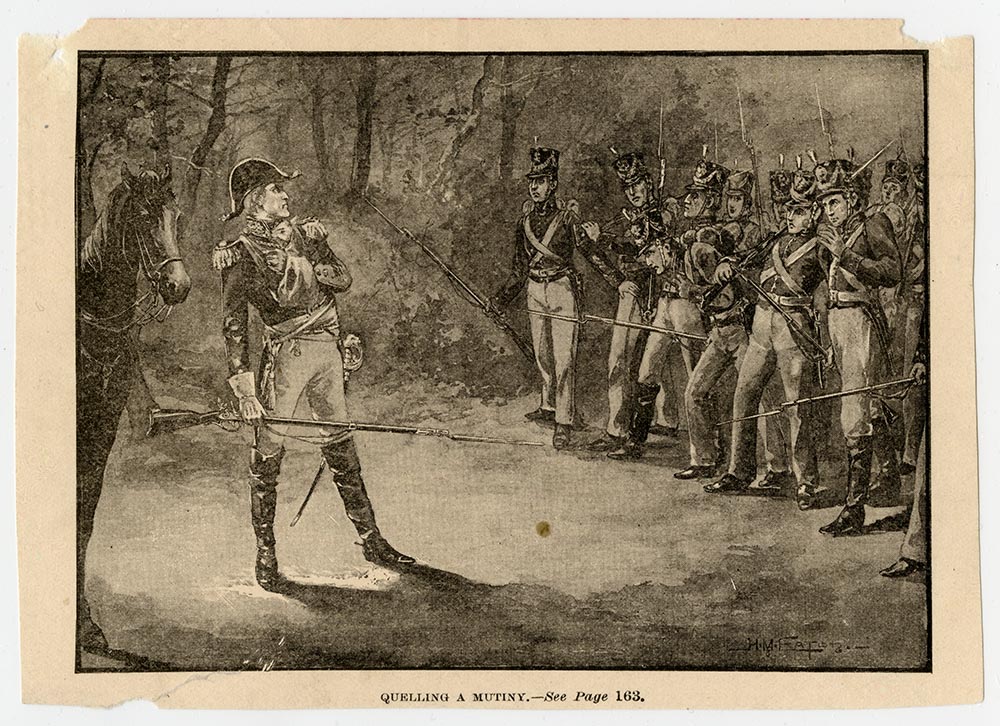

Anti-British feeling ran high in Tennessee, and Tennesseans were easily willing to link the Native American threat with British actions on the high seas. Led by Felix Grundy of Nashville, the state’s representatives were prominent among the “War Hawks” in Congress, who wanted to go to war with Great Britain. When war was declared in June 1812, Tennesseans saw an opportunity to rid their borders once and for all of Native Americans. Their chance came soon enough. News reached Nashville in August 1813 of the massacre of some 250 men, women, and children at Fort Mims, Alabama. Tecumseh’s message had taken hold, and the Creek Nation was split by civil war. The Fort Mims attack was carried out by the war faction, called Red Sticks, under their chief, William Weatherford. Governor Willie Blount immediately called out 2,500 volunteers and placed them under the command of Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s 1813–1814 campaign against Weatherford’s warriors, known as the Creek War, was the Southern phase of the War of 1812. Jackson faced many challenges including lack of support from the War Department, shortages of supplies, and a mutiny, or rebellion, by some of his soldiers. Despite these problems, Jackson won several victories against the Red Sticks. His victory at the Battle of Tohopeka, or Horseshoe Bend, utterly destroyed Creek military power. As a result, Andrew Jackson and his lieutenants, William Carroll and Sam Houston, gained national prominence, or importance.

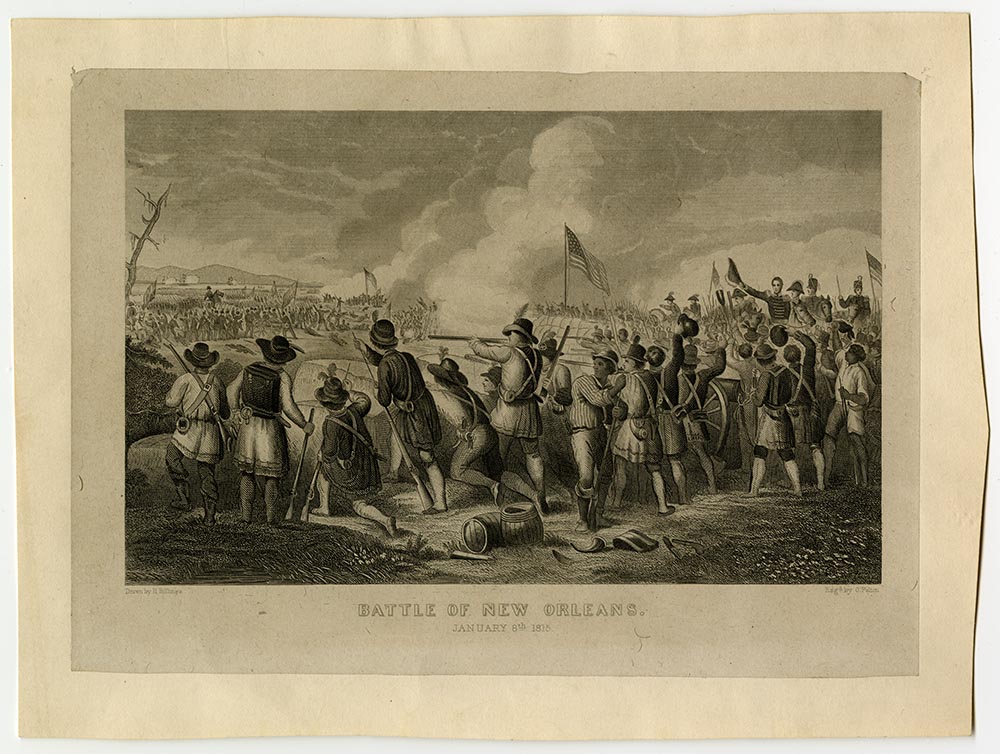

Following his victory over the Creeks, Andrew Jackson was appointed major general in the U.S. Army and given command of the Southern military district just in time to meet an impending British invasion of the Gulf Coast. Jackson secured Mobile, Alabama and drove the British out of Pensacola, Florida. Jackson then hurriedly marched his troops to New Orleans to rendezvous, or meet, with other Tennessee units converging to defend the city. On January 8, 1815, Jackson’s ragtag troops inflicted a crushing defeat on an experienced British army. British general Sir Edward Pakenham was killed along with hundreds of his soldiers. The Americans only suffered twenty-three casualties. Because of poor communication, the battle actually occurred fifteen days after the signing of the peace treaty with Great Britain in Ghent, Belgium. The Battle of New Orleans was a brilliant victory and one of the few clear American successes of the war. This triumph launched Andrew Jackson on the road to the presidency. Three years later, he led another force of Tennesseans into Florida to stop attacks by the Seminoles. Jackson’s actions in Florida convinced Spain to cede Florida to the United States.

After forcing Creeks to cede their land claims, Jackson and Governor Isaac Shelby of Kentucky negotiated a treaty with the Chickasaw in 1818 that extended Tennessee’s western boundary to the Mississippi River. The agreement, also known as the Jackson Purchase, opened up a rich, new agricultural region for settlement. By 1820, the only Native Americans remaining in Tennessee were squeezed into the southeast corner of the state. The arrival of large numbers of settlers and a booming land market in West Tennessee caused a frantic period of business prosperity, which ended suddenly with the Panic of 1819. This brief but violent economic depression ruined most banks and many individuals. However, the state’s economy bounced back quickly. Cotton became the leading crop in West Tennessee, and Memphis became a center of the cotton trade. Tennesseans could look back on their first twenty-five years of statehood as a period of growth and prosperity comparable to that of any state in the nation.