Tennessee’s problems did not end when the war was over, but continued during the postwar period known as Reconstruction. The war’s legacy of political bitterness endured for years after the surrender of Confederate armies. The war split Tennessee’s society into rival groups who wanted to get revenge on each other. Each side wanted to use political power to punish its enemies and stop them from participating in the political system. This political fighting was only slightly less violent than the war that had just ended.

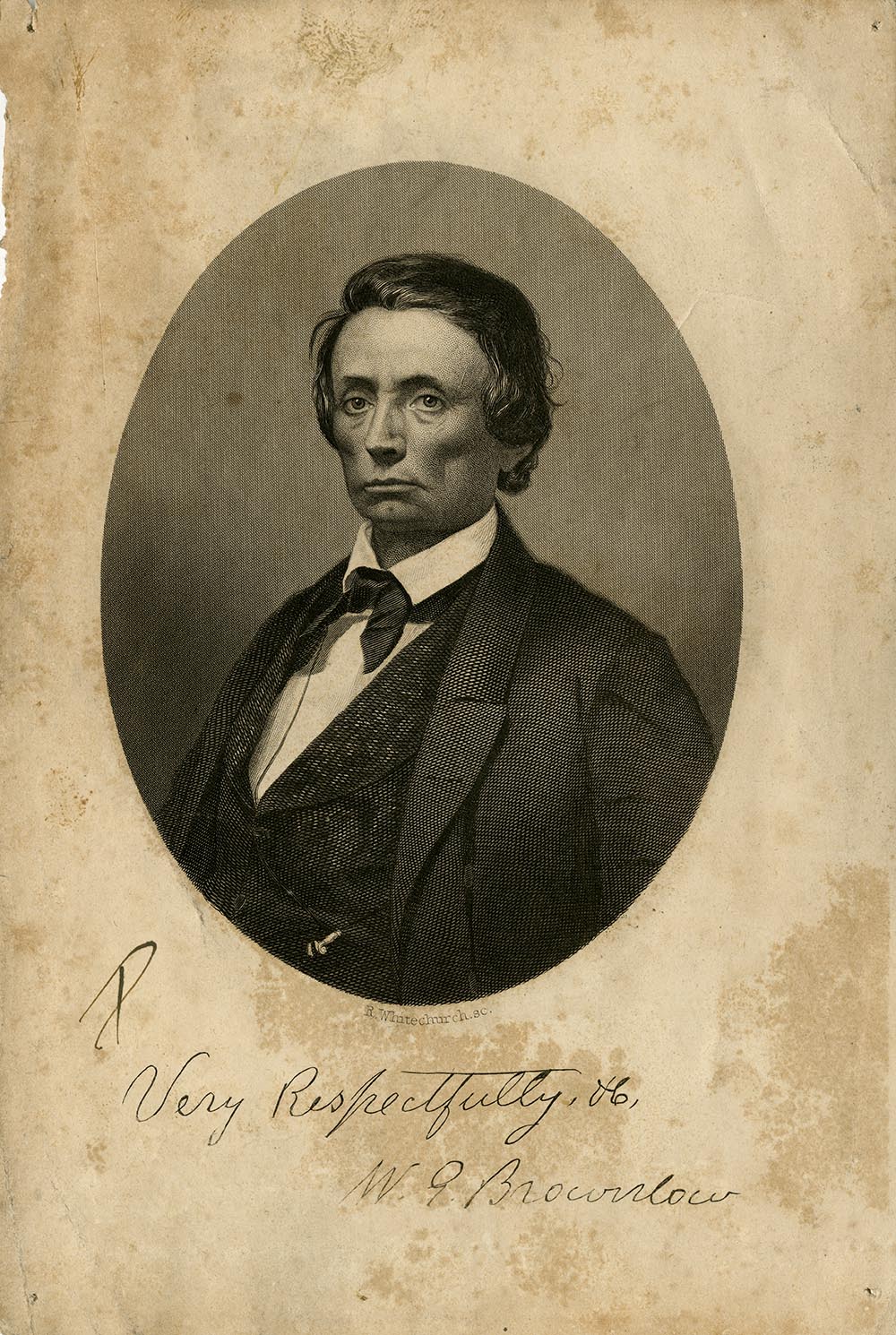

President Lincoln’s formula for reconstructing the Southern states required that only ten percent of a state’s voters take the oath of allegiance and form a loyal government before that state could apply for readmission. In 1864, Lincoln selected Tennessee Unionist and Democrat Andrew Johnson as his vice presidential running mate. Lincoln selected Johnson because he wanted to show Southerners that the South would receive fair treatment when the war was over. In January 1865, after Andrew Johnson departed for Washington to become Lincoln’s vice president, a group of Tennessee Unionists met in Nashville to begin the process of restoring Tennessee to the Union. They nominated William G. “Parson” Brownlow of Knoxville for governor, rejected the act of secession, and planned a vote on an amendment to the state Constitution abolishing slavery. About 25,000 voters approved the amendment and elected Brownlow as governor, essentially meeting the requirements of Lincoln’s plan. Tennessee became the only seceded state to abolish slavery by its own act.

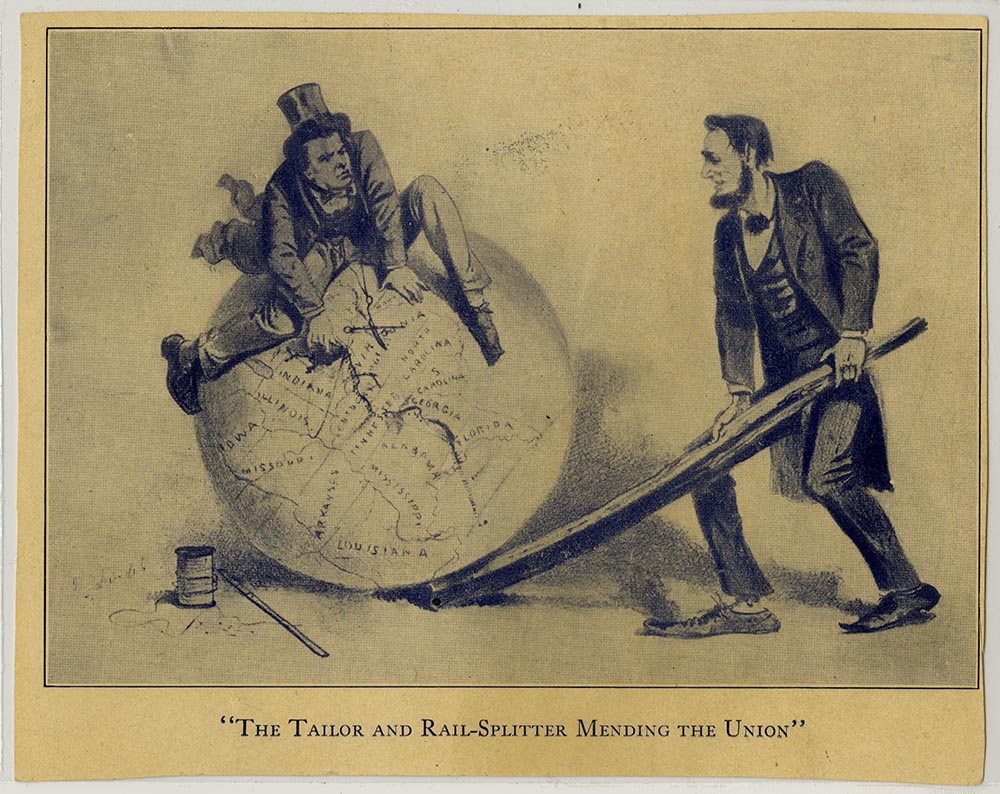

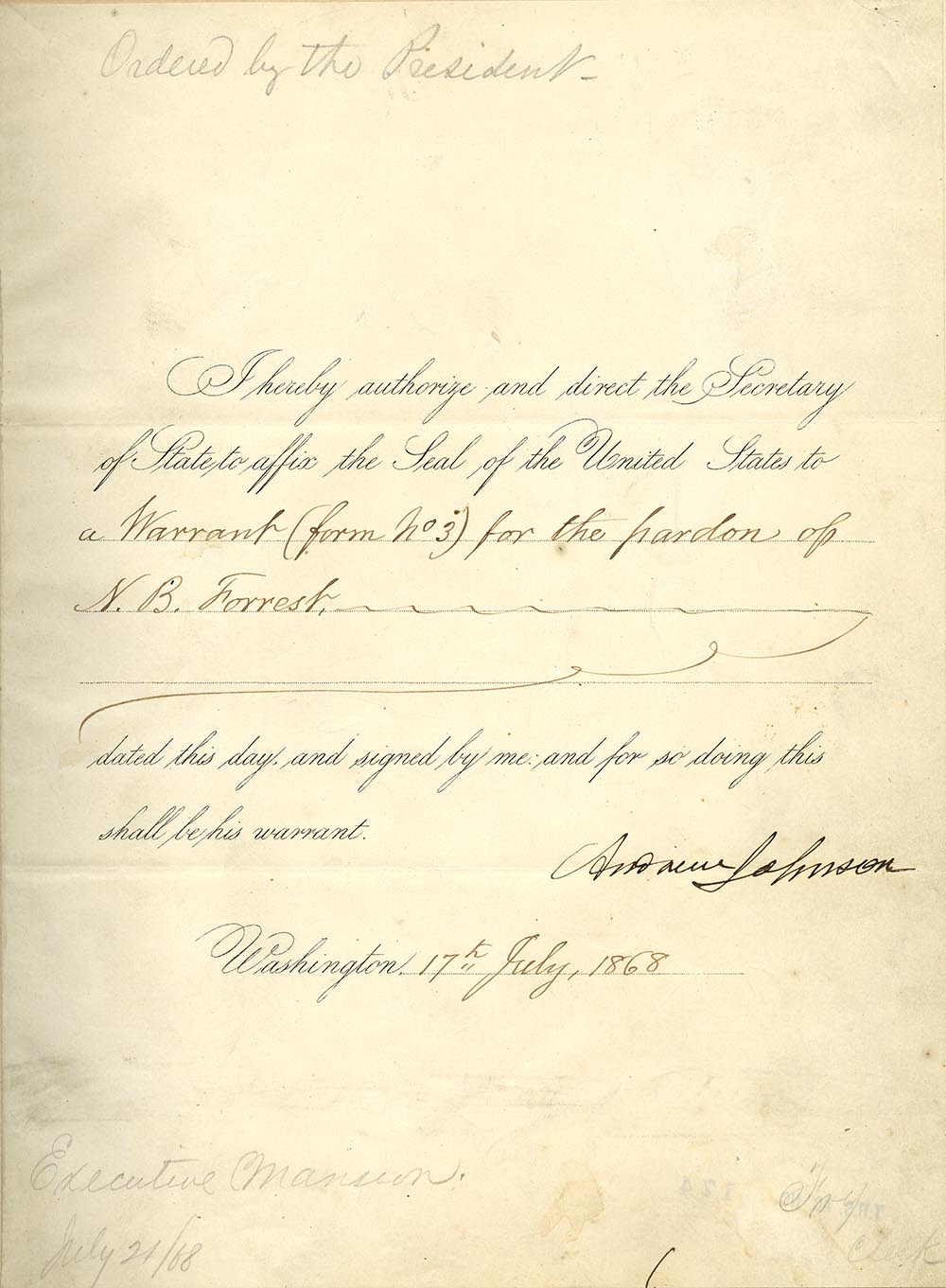

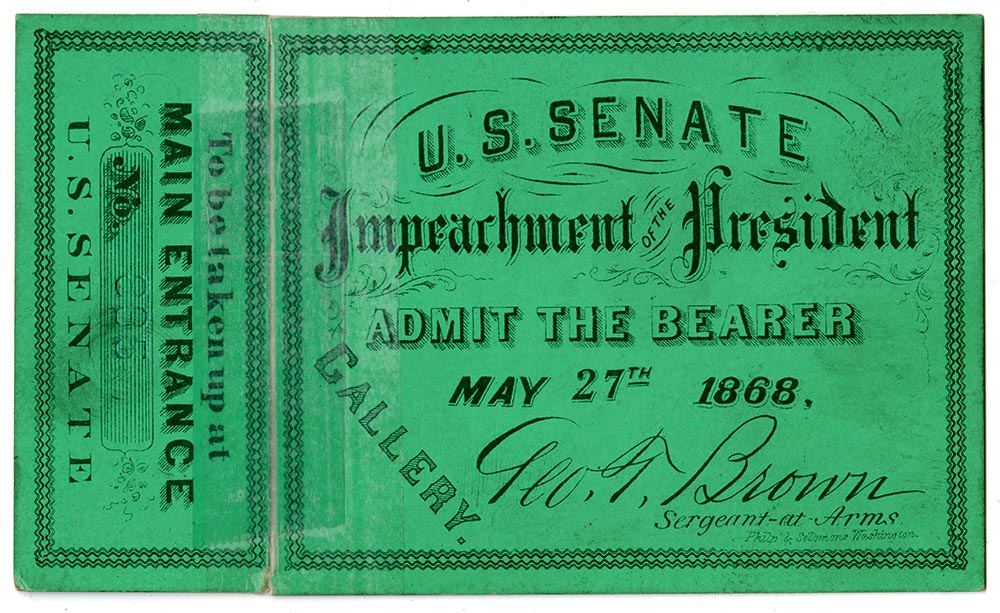

Lincoln’s assassination in April launched Johnson into the presidency and signaled a drastic shift in the course of Reconstruction. The Radical Republicans were gaining power in Congress, and they wanted to punish the South more than either Lincoln or Johnson did. Johnson was not a very skillful negotiator, and he soon found himself in conflict with the Radical Republicans. Congress refused to seat Tennessee’s congressional delegation. Members of Congress claimed that Johnson’s plan to give amnesty, or forgiveness, to most former Confederates was too lenient. Congress ordered that only states that extended citizenship and legal protection to freedmen and denied voting rights to former Confederates by ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment would be readmitted. Ultimately, Johnson’s conflict with Congress would lead to his impeachment. Though Johnson was acquitted of the charges, he did not run for reelection in 1868.

Many Tennesseans opposed the Fourteenth Amendment because it denied former Confederates the right to participate in government. Despite these objections, Brownlow was able to force the General Assembly to ratify the amendment on July 18, 1866. This action paved the way for Tennessee’s early readmission to the Union. Tennessee became the third state to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, before any other Southern state and earlier than most Northern states. Though many citizens despised Brownlow’s government, it ensured that Tennessee rejoined the nation sooner than any other seceded state. More importantly, it meant that Tennessee would be the only Southern state to escape the harsh military rule inflicted by the Radical Congress.

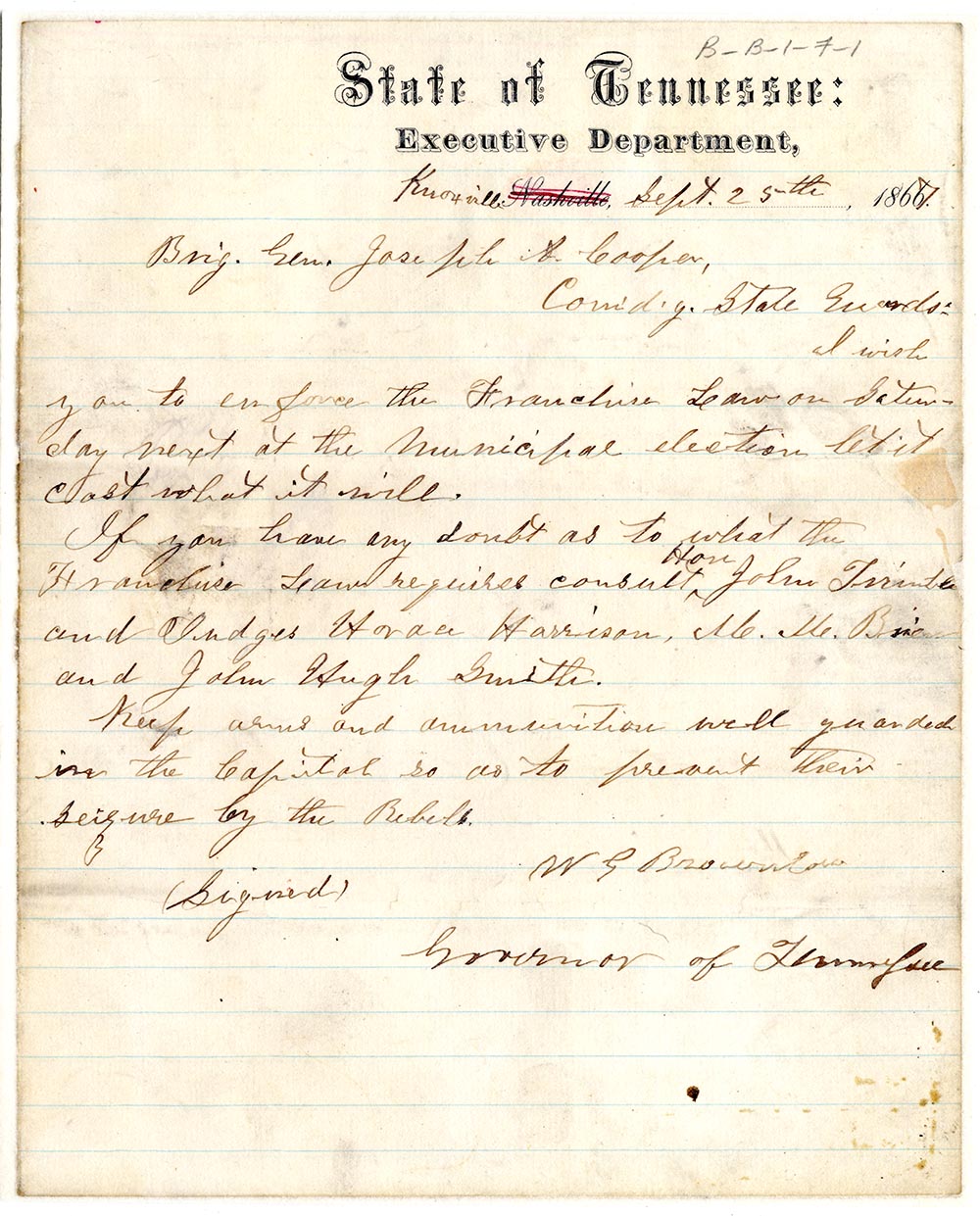

Governor Brownlow’s administration cooperated with the Radical Republicans in Congress, but not with the majority of the people in its own state. Brownlow faced considerable opposition from other Unionists who resented his undemocratic methods. Therefore, he decided to give the vote to freedmen in order to strengthen his support at the polls. Accordingly, in February 1867, the Tennessee General Assembly declared its support for giving voting rights to African American males. This came two years before Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment. With the help of African American voters, Brownlow and his slate of candidates swept to victory in the 1867 elections. A slate of candidates is a group of political candidates who share a set of political views.

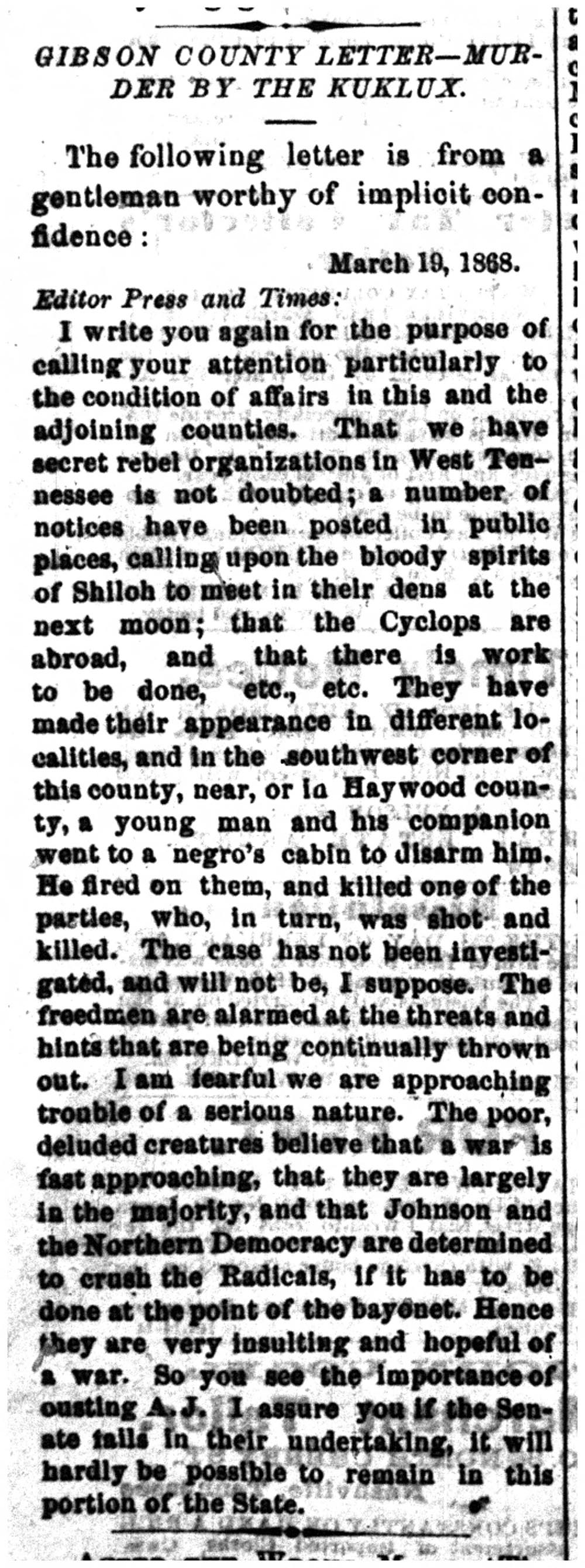

Brownlow’s unpopular and undemocratic government caused its own downfall. The Ku Klux Klan emerged in the summer of 1867, one of several shadowy vigilante groups opposed to Brownlow and freedmen’s rights. Vigilantes are people who use violence to enforce the rules or laws of their society. In this case, the Klansmen wanted to enforce the pre-Civil War rules that denied rights to African Americans. These groups were made up largely of ex-Confederates. Their goal was to intimidate the African American voters by attacking their homes and families. Many former Confederates joined the Ku Klux Klan because it was the only political organization open to them while Brownlow was governor. In 1869, Brownlow was selected to fill a seat in the United States Senate. With Brownlow gone, the Klansmen saw a path back to political power. The group officially disbanded in 1869 but would be revived in the early twentieth century.

Brownlow’s departure for Washington gave conservatives a chance to bring ex-Confederates back into state government. Brownlow’s successor, DeWitt Senter, was also thought to be a Radical Republican. However, once Senter took office, he allowed ex-Confederates to register to vote. As a result of their support, Senter easily won the governorship in the election of 1869. Seven times as many Tennesseans voted in 1869 than in 1867.

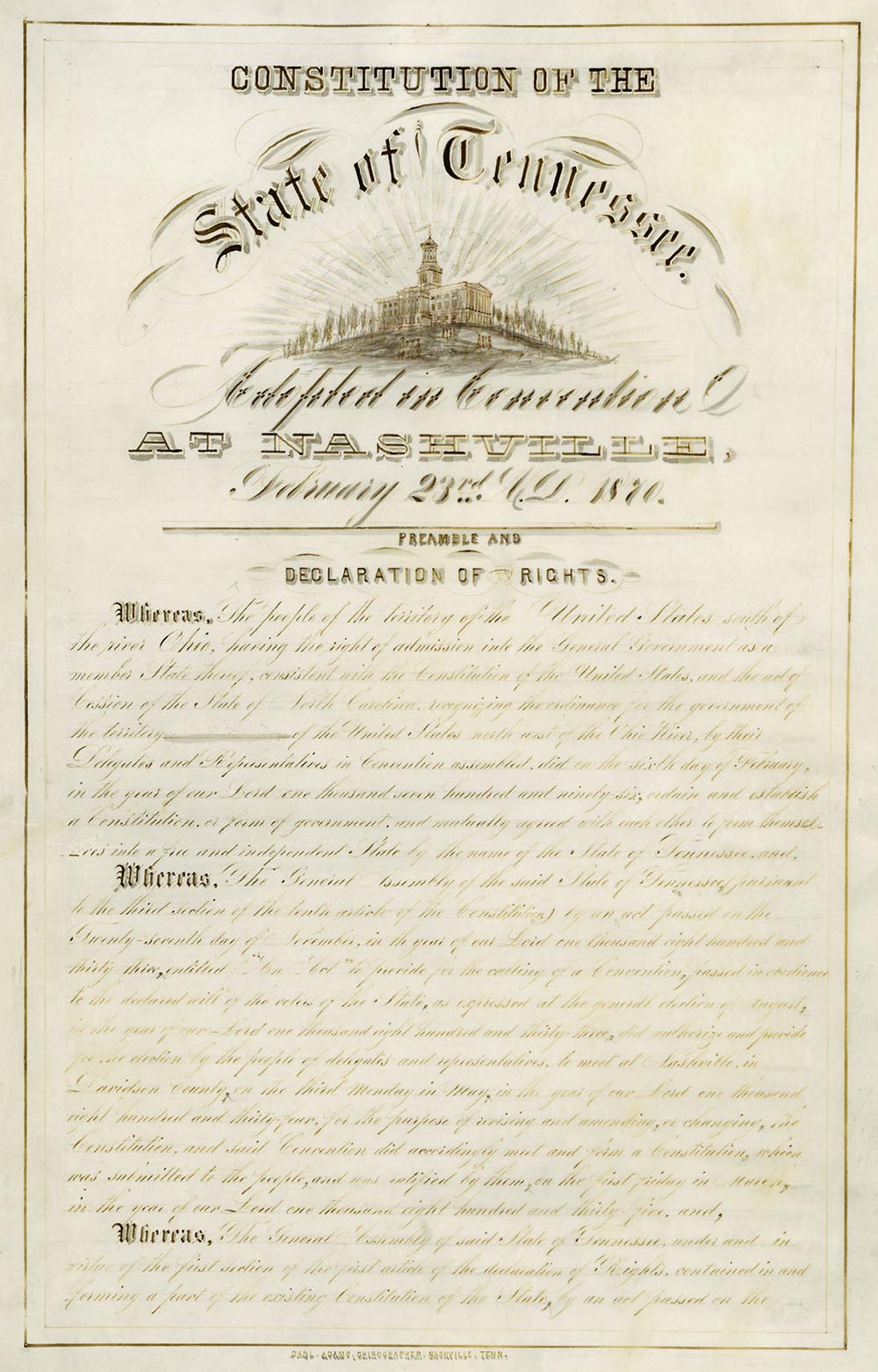

In 1870, delegates from across the state met to rewrite the state Constitution. While the delegates were mostly conservatives, they were careful to write a constitution that would allow Tennessee to avoid Federal military occupation. Delegates ratified the abolition of slavery and voting rights for freedmen but limited voter participation by enacting a poll tax. A poll tax is a tax that must be paid before a person can vote. Political reconstruction effectively ended in Tennessee with the rewriting of the Constitution, but the struggle over the civil and economic rights of black freedmen had just begun.

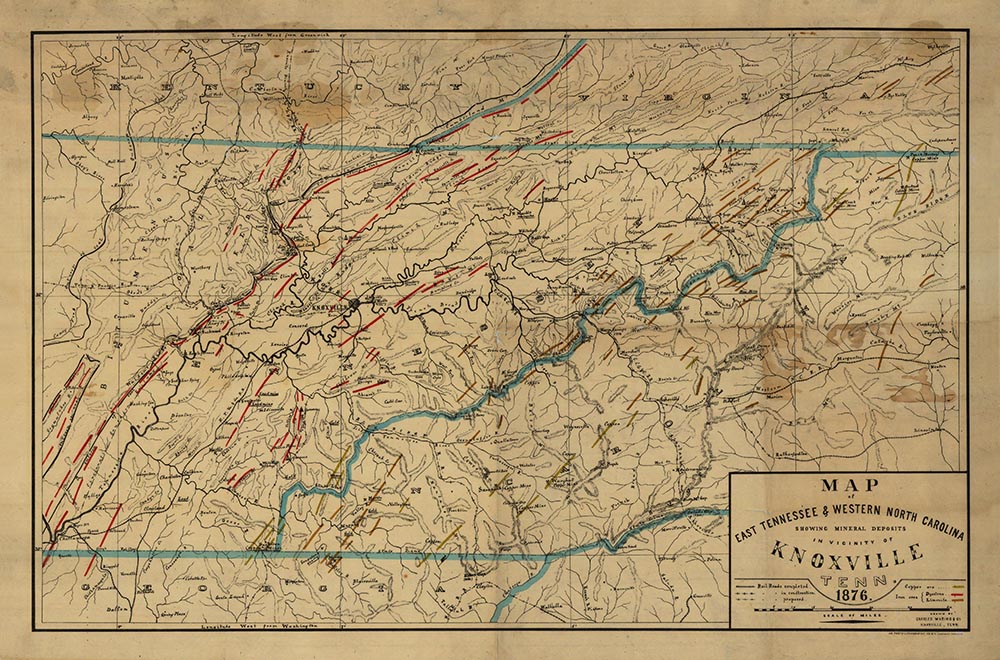

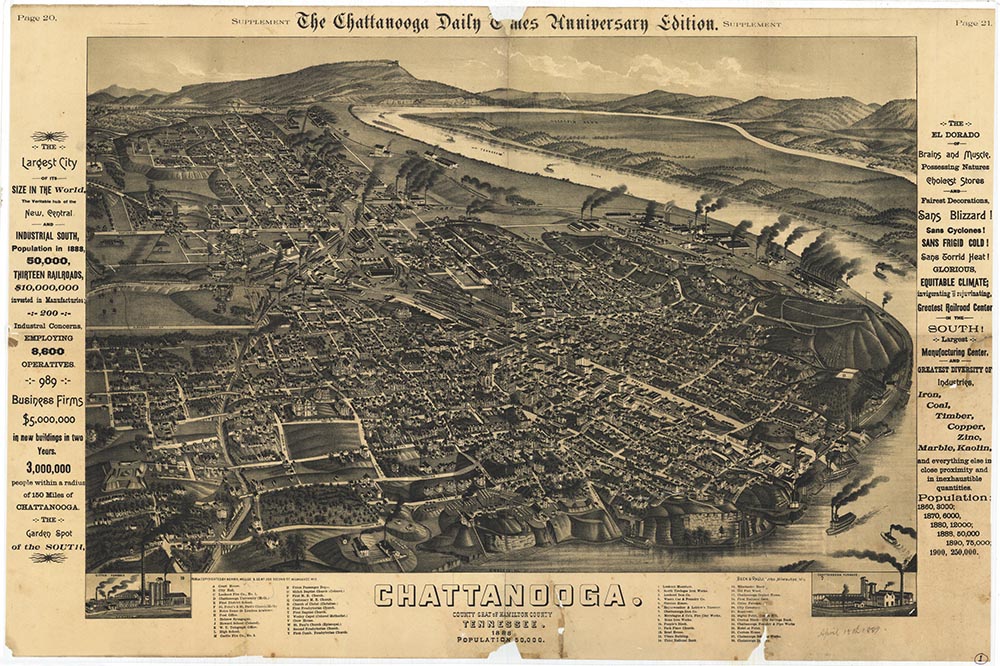

After the war, African Americans faced more difficulties than most other Tennesseans. Many freedmen left the plantations and rural communities for urban areas such as Memphis, Nashville, Chattanooga, and Knoxville looking for work and a chance to improve their lives. Freedmen also fled the countryside to escape the violence of groups like the Klan. These newcomers settled near military encampments where black troops were stationed. Over time, these areas developed into major African American communities such as North Nashville and South Memphis. In time, an African American professional and business class developed in the cities.

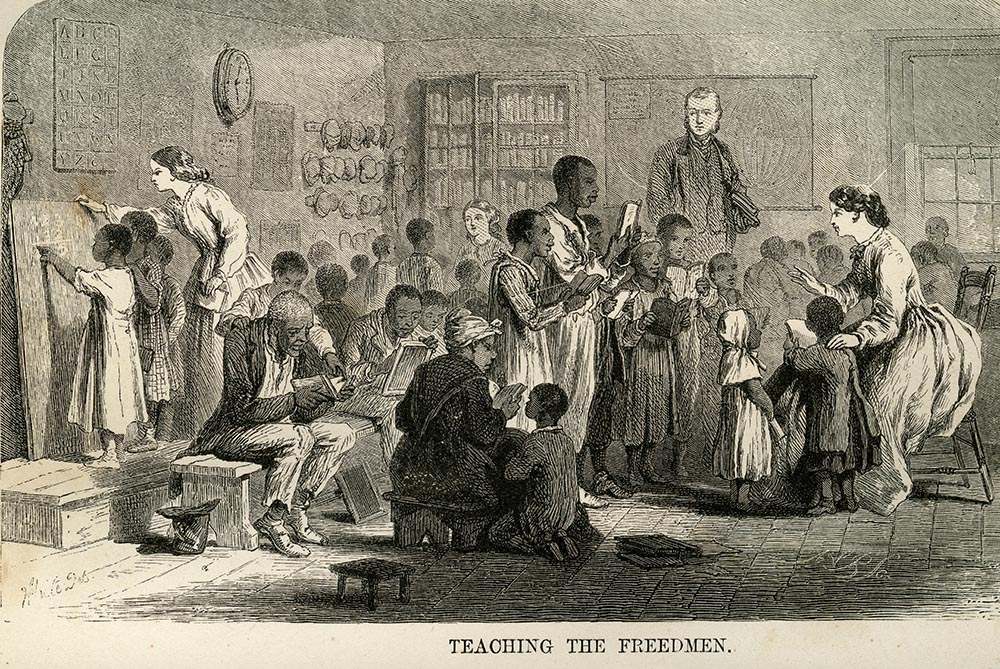

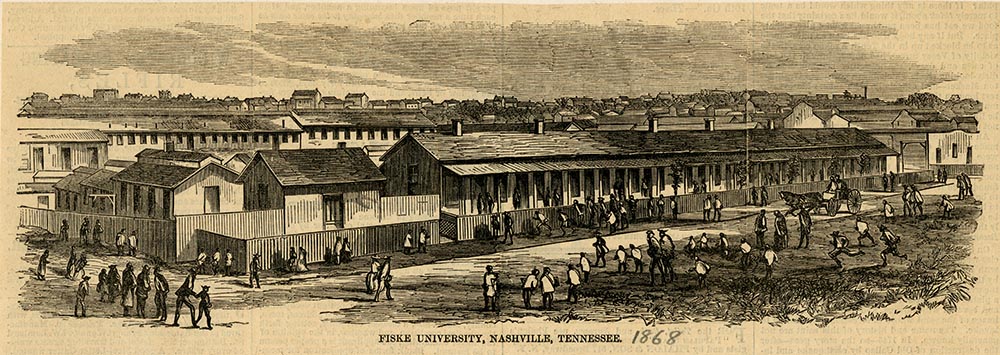

One institution created specifically to aid former slaves was the Freedmen’s Bureau. With help from Northern missionaries, the Freedmen’s Bureau set up hundreds of public schools for African Americans. Freedmen responded enthusiastically to the new schools, and a number of colleges—Fisk, Tennessee Central, LeMoyne, Roger Williams, Lane, and Knoxville—were soon founded to meet the demand for higher education. However, the Freedmen’s Bureau was not generally successful in helping African Americans acquire their own land. Most African Americans in the countryside were laborers or tenant farmers. After the army left in 1866, the Freedmen’s Bureau declined in influence. In the future, Tennessee freedmen had to rely on themselves and their own leaders to advance their goals.

African Americans were politically active and exercised their newfound legal rights even after the Radical Republicans lost power in 1869. They brought suits in the county courts, filed wills, and ran for local elected offices, particularly in the cities where they commanded strong voting blocs. A voting bloc is a group of voters who share common concerns and therefore vote for the same candidates. Beginning with Sampson Keeble of Nashville in 1872, thirteen black legislators were elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. Much of their legislative work consisted of trying to protect the rights gained during Reconstruction. S. A. McElwee, Styles Hutchins, and Monroe Gooden, elected in 1887, would be the last black lawmakers to serve in Tennessee until the 1960s.

Once the Democrats regained political power, they began to reverse the movement towards racial equality. The Klan had enforced white supremacy with lynchings, beatings, and arson. Lynchings are illegal executions usually carried out before the accused has a trial. Beginning in the 1870s, the Legislature began to pass laws designed to make African Americans second-class citizens. These laws were called “Jim Crow” laws after a character in a popular traveling show. Poll taxes and literacy tests targeted African American voters and greatly reduced the number of African Americans participating in the political system. By the 1880s, the Legislature demanded separate facilities for whites and blacks in public accommodations, like boarding houses, and on railroads.

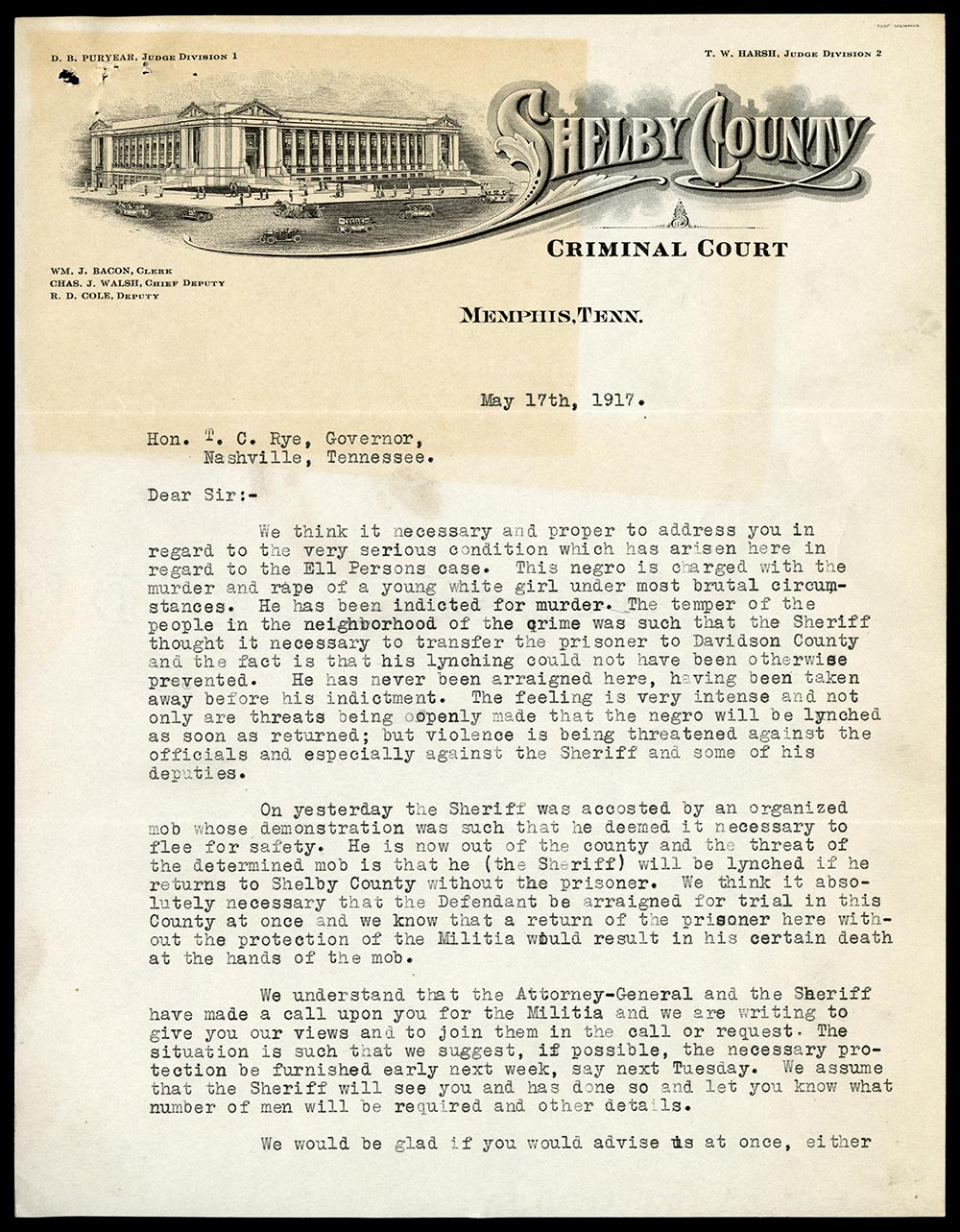

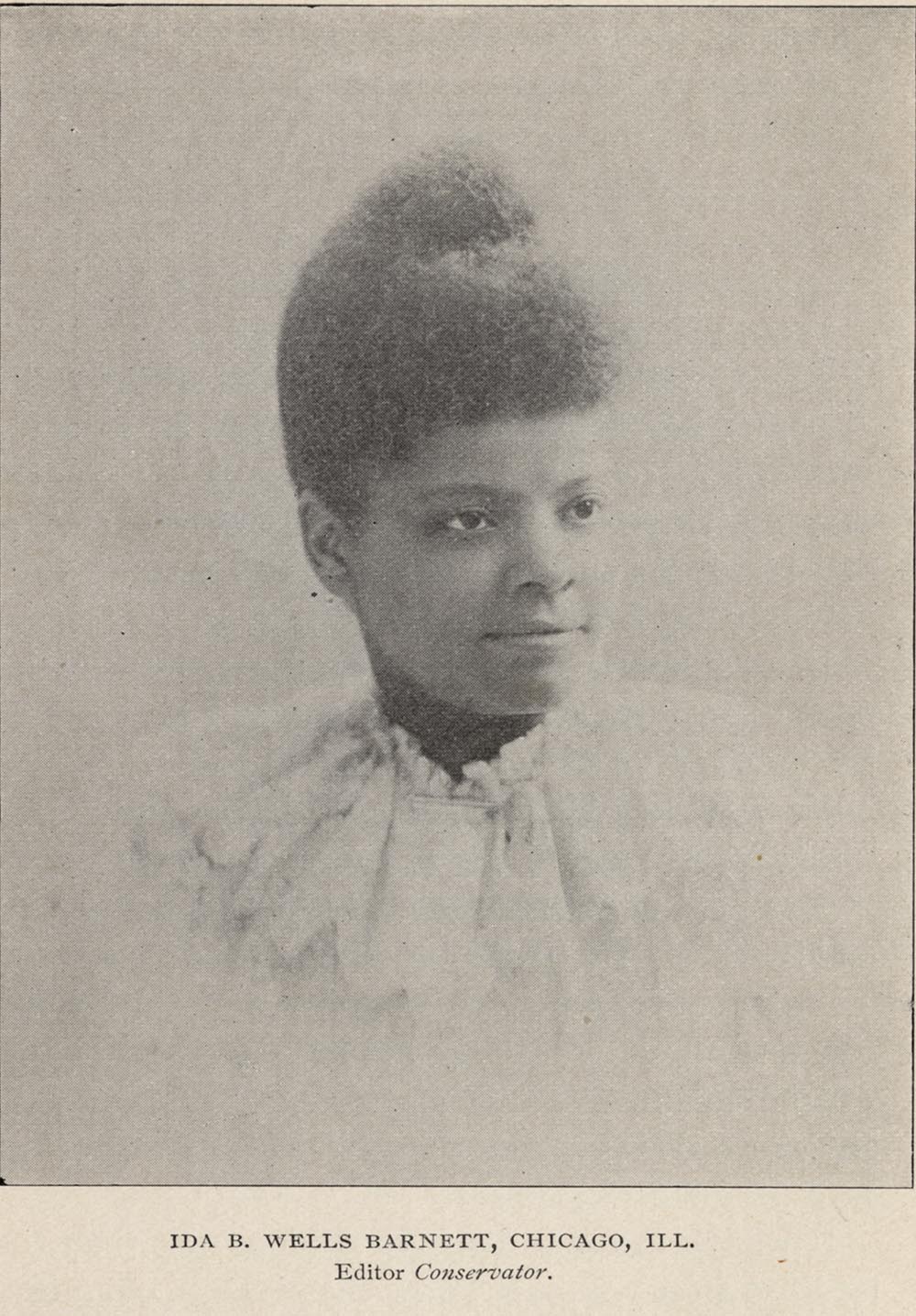

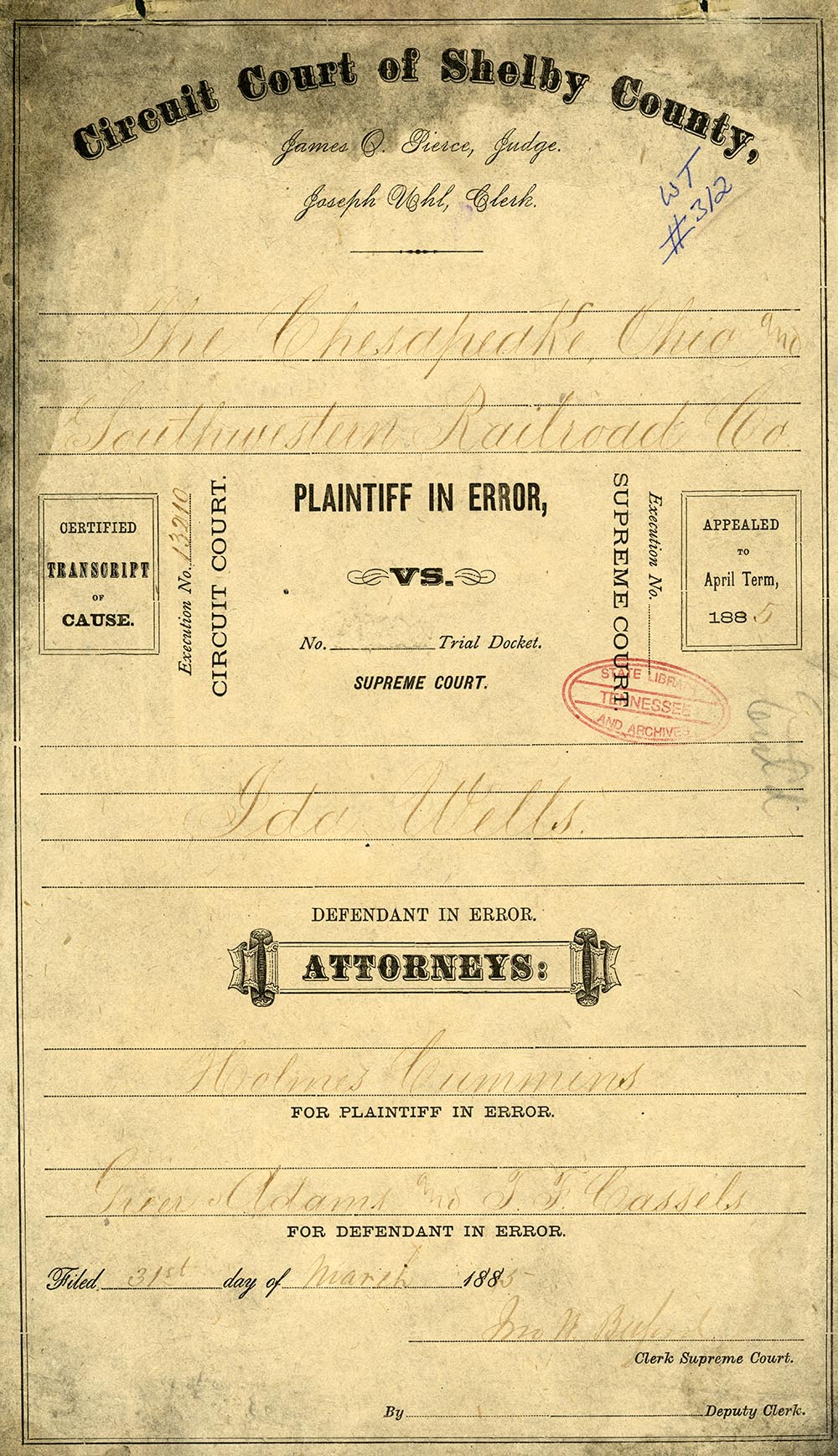

One young woman, Ida B. Wells, challenged the “separate but equal” law on the railroads in an 1883 court case. Wells had purchased a ticket for the ladies’ car and refused to give up her seat when the conductor demanded she move to the “Jim Crow” car. Wells later sued the railroad company and won in the lower courts, but the Tennessee State Supreme Court ruled against her. Wells moved to Chicago and spent the rest of her life fighting for equality for African Americans and women. She drew the nation’s attention to the use of lynching as a means of terrorism against African Americans in her book Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. Former slave and Chattanooga newspaperman Randolph Miller also fought discrimination in Tennessee. Miller helped to organize a boycott of Chattanooga’s streetcars after they were segregated.

Nashvillian Benjamin Singleton also worked to improve the lives of African Americans. Singleton urged his fellow freedmen to leave the South altogether to homestead in Kansas. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave settlers the opportunity to claim 160 acres of public land in the West. Homesteaders had to pay a small fee and live on the land continuously for five years. The freedmen who moved to Kansas were known as Exodusters. Another group of African Americans who played an important role in the settlement of the West were the Buffalo Soldiers. Many Buffalo Soldiers were former slaves who joined the Union army after emancipation. Buffalo Soldiers like Tennessean George Jordan played an important role in the Indian Wars of the late 1800s. Jordan was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1890 for his leadership in an 1880 battle against Apaches. Despite receiving this honor, Jordan died in 1904 after being denied treatment at Fort Robinson’s hospital because he was African American.

One response to the labor shortage and property losses caused by the war was the campaign to rebuild a “New South” based on industry, skilled labor, and outside capital. Promoters and state officials worked hard to attract skilled foreign immigrants to the state. The state never succeeded in attracting a large number of immigrants. However, a few isolated German and Swiss colonies, such as Gruetli in Grundy County, were formed. As late as 1880, the foreign-born part of Tennessee’s population was still only one percent, compared with a national average of fifteen percent.

“New South” advocates backed the educational reform act of 1873. The act tried to establish regular school terms and reduce the state’s high illiteracy rate. A statewide administrative structure and general school fund were created, but the Legislature failed to give the schools enough money to operate full time. Better progress was made during the 1870s in the field of higher education: Vanderbilt University was chartered; East Tennessee College was converted to the University of Tennessee; and Meharry Medical College, the first African American medical school in the nation, was founded. Finally, the University of Nashville became the Peabody State Normal School, one of the earliest Southern colleges devoted exclusively to training teachers.

The “New South” promoters also met with some success in attracting outside capital to Tennessee. Northern businessmen, many of whom had served in Tennessee during the war, relocated here to take advantage of cheap labor and abundant natural resources. Some Tennesseans viewed these businessmen as opportunists and referred to them as “carpetbaggers” because many of the men arrived with their belongings in carpetbags. Perhaps the most prominent of these “carpetbaggers” was General John Wilder, who built a major ironworks at Rockwood in Roane County. Chattanooga’s iron and steel industry benefited greatly from Northern money. The city grew rapidly into one of the South’s leading industrial cities. In 1899, three lawyers from Chattanooga bought the rights to bottle Coca-Cola. The men then sold the right to bottle Coca-Cola to businessmen throughout the country. By 1890, the value of manufactured goods produced in Tennessee reached $72 million. Before the war, Tennessee only produced about $700,000 worth of manufactured goods per year.

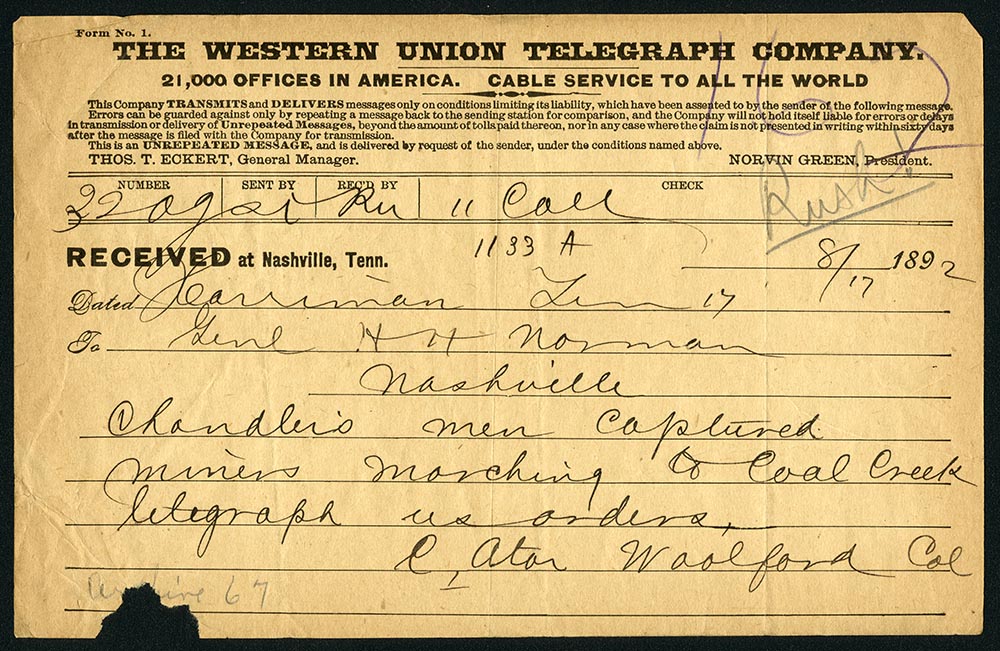

State funding for railroad construction left Tennessee $43 million in debt. Tennessee’s lawmakers debated how to pay the debt for many years. One method that the state used to raise revenue, or income, was the infamous convict lease system. In this system, prisoners were leased to private businesses as laborers. The business was responsible for providing food and shelter for the prisoners and preventing them from escaping. Legislators liked this system because it earned money for the state and prevented the state from having to build a new prison. In 1871, Tennessee began leasing prisoners for work in the coal mines of East Tennessee. In the Cumberland Plateau region, the largest mine operator was the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI). In 1884, TCI signed an exclusive lease with the state for the use of convicts in its mines. In addition to keeping labor costs low, convict lease labor was one means of overcoming strikes. According to A. S. Colyar, TCI’s president, “The company found this an effective club to hold over the heads of free laborers.”

Trouble erupted in 1891 at mines in Anderson and Grundy Counties, when TCI used convicts as strikebreakers against striking coal miners. Miners began releasing convicts and burning down the stockades where they were housed. Violence in the coal fields peaked during the summer of 1892, when state militia was sent to the Coal Creek area by Governor John Buchanan. The militia fought a series of battles with armed miners, known as the Coal Creek War. More than 500 miners were arrested, and twenty-seven miners were killed. The Coal Creek War convinced the General Assembly to end convict leasing in 1895 when the TCI contract expired, making Tennessee one of the first Southern states to get rid of the system. The state also built two new prisons at Nashville and Brushy Mountain in Morgan County. Prisoners at Brushy Mountain mined coal in state-owned mines.

Though most Tennesseans were still farmers, it became harder and harder for them to earn a living. Before the war, Tennessee’s farmers had grown a wide variety of crops. After the war, farmers concentrated on growing cash crops such as cotton, tobacco, and peanuts. Falling farm prices, high railroad rates, and the Depression of 1873 all worked against independent farmers. As a result, many farmers became sharecroppers. Sharecroppers rented land to farm and paid the landowner by giving him a portion of the crop they produced. Sharecroppers were nearly always in debt at high interest rates for land, tools, and supplies, and they were typically the poorest class of farmers.

In the 1880s, Tennessee farmers began to organize in a series of political movements. In 1886, votes from farmers helped Robert Taylor win the race for governor. Taylor defeated his brother in the famous “War of the Roses” campaign. Three years later, a farmers’ organization called the Agricultural Wheel signed up 78,000 members in Tennessee, more than in any other state. The Wheel later merged with an organization called the Farmers’ Alliance to create a strong grassroots movement. A grassroots movement is a political or social movement that begins with people on the local level.

In 1890, Alliancemen put their candidate, John Buchanan, in the Governor’s Office. Buchanan’s farmer-dominated Legislature passed the first pension act for Confederate veterans. The pension act allowed Confederate veterans or their families to receive a small monthly payment from the state. However, Buchanan’s popularity suffered as a result of his handling of the Coal Creek uprising. The Tennessee Alliance joined with the newly formed Populist Party to organize a serious challenge to the traditional two-party system. Democrats, however, spread rumors that the Populists and Republicans had made a deal. The Democrats also criticized the alliances for admitting African American members, which damaged the Populists’ reputation among white farmers. By 1896, the Populists and Farmers’ Alliance had virtually disappeared in Tennessee, another victim of the dismal racial politics of the period.

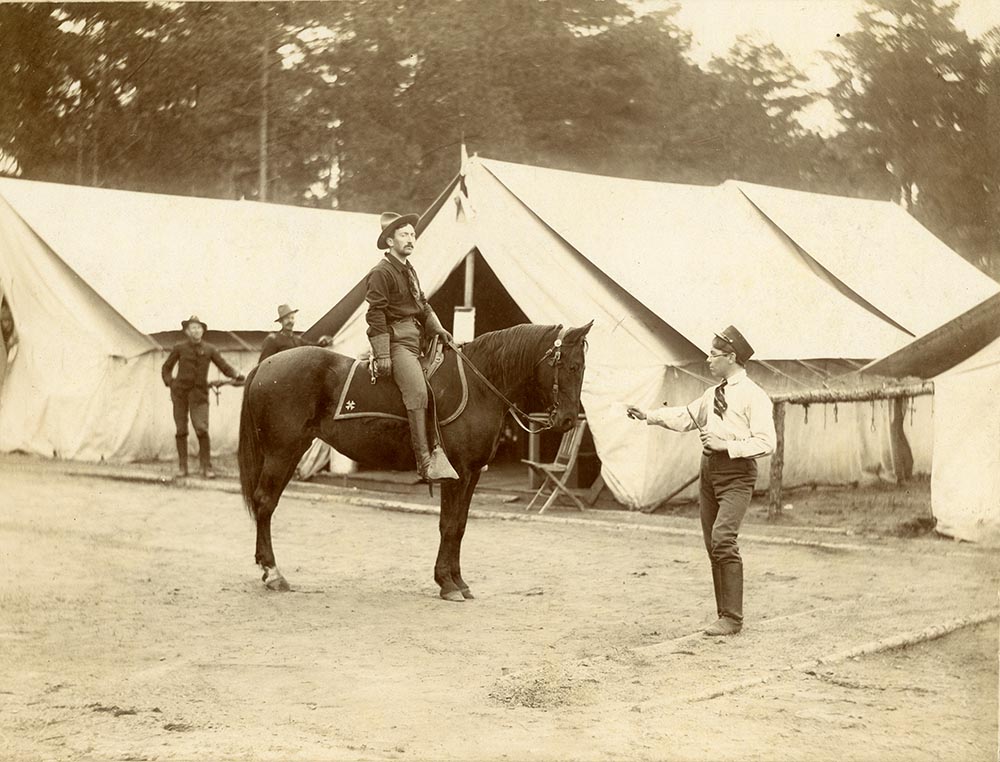

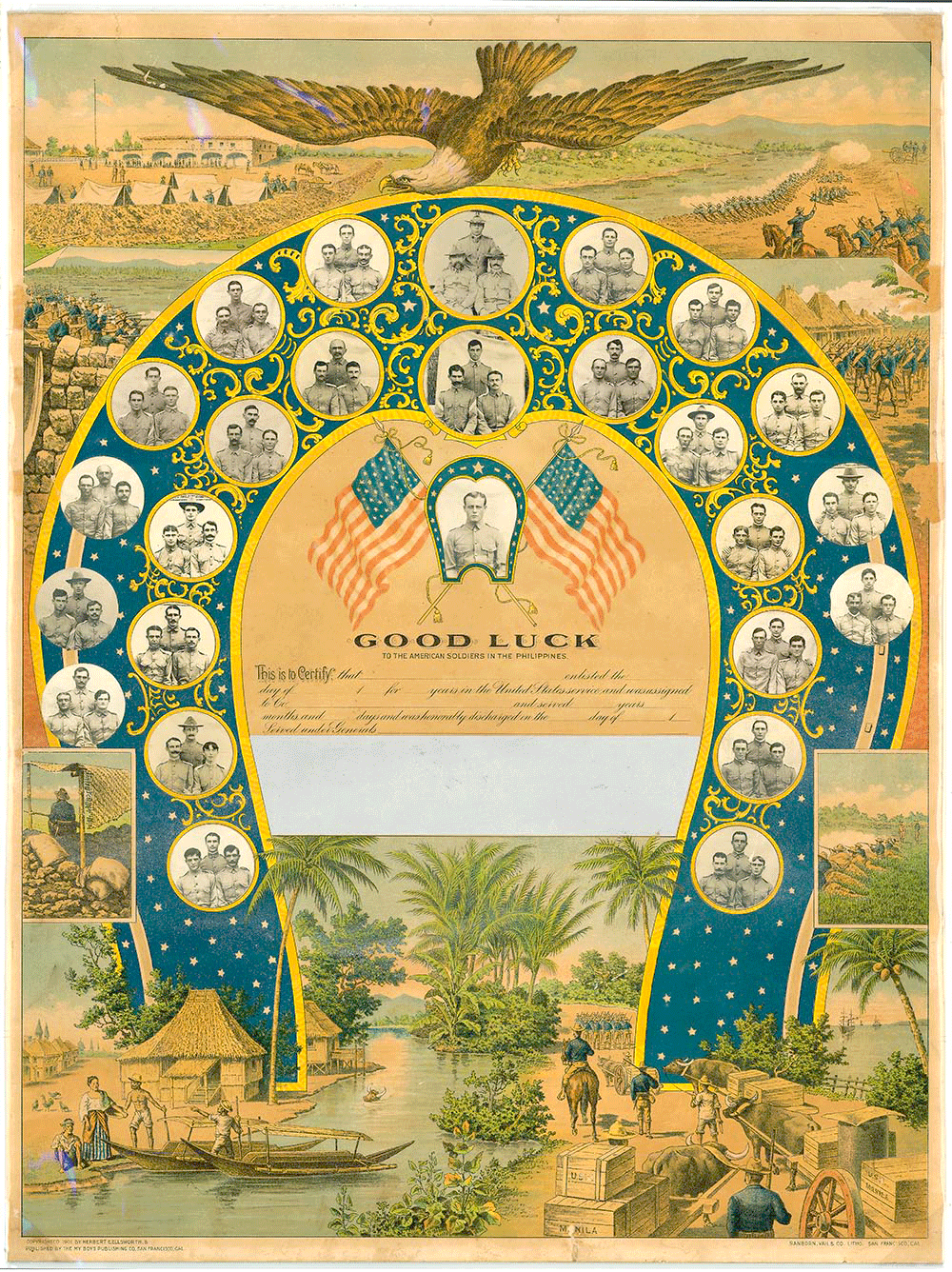

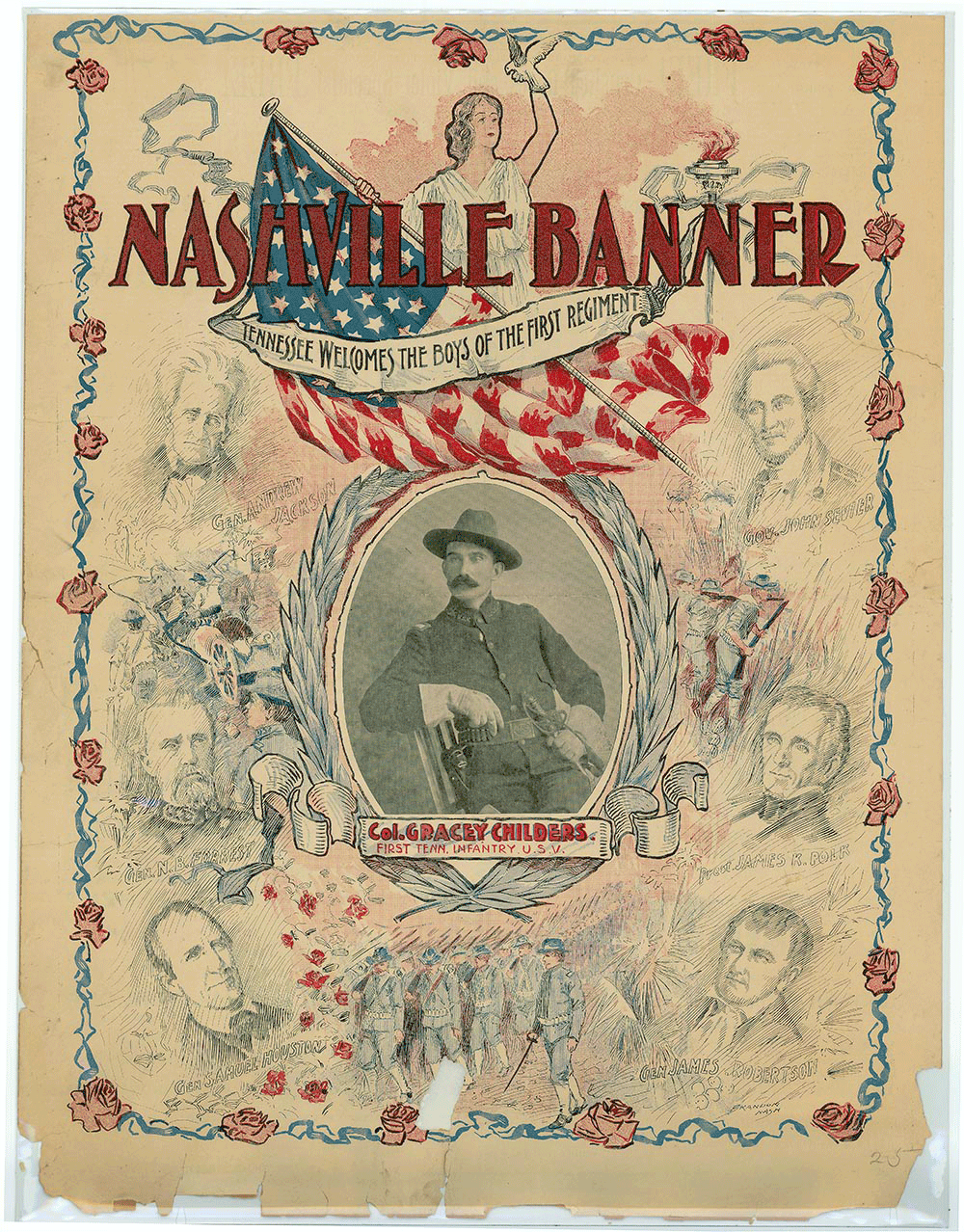

The state continued its military tradition. When the Spanish-American War began in 1898, four regiments of Tennesseans volunteered for the United States Army. The Second, Third, and Fourth Regiments were sent to Cuba, where they suffered from heat and disease but saw little action. The First Tennessee Infantry was dispatched to San Francisco and then by troopship to Manila in the Philippines. There, these troops aided in the suppression of the Filipino nationalist movement, returning to Nashville late in 1899.

Late nineteenth-century Tennessee has been called a “social and economic laboratory” because of the variety of experimental communities established here. The state became home to a number of utopian colonies, land company settlements, and recreation spas. Leaders of utopian communities wanted to create perfect communities based on their individual philosophies. These communities were formed in part due to the availability of cheap land in remote natural surroundings.

In 1880, some absentee landowners sold English author Thomas Hughes a large tract of land in Morgan County, on which he established the Rugby colony. For the next twenty years, English and American adventurers settled here to take part in the intellectual and vocational opportunities Rugby offered. Another experimental colony was Ruskin, founded in 1894 by the famous socialist publicist Julius Wayland. Located on several hundred acres in rural Dickson County, Ruskin was a cooperative community in which wealth was held in common, and members were paid for their work in paper scrip based on units of labor. Both Rugby and Ruskin had declined by 1900.

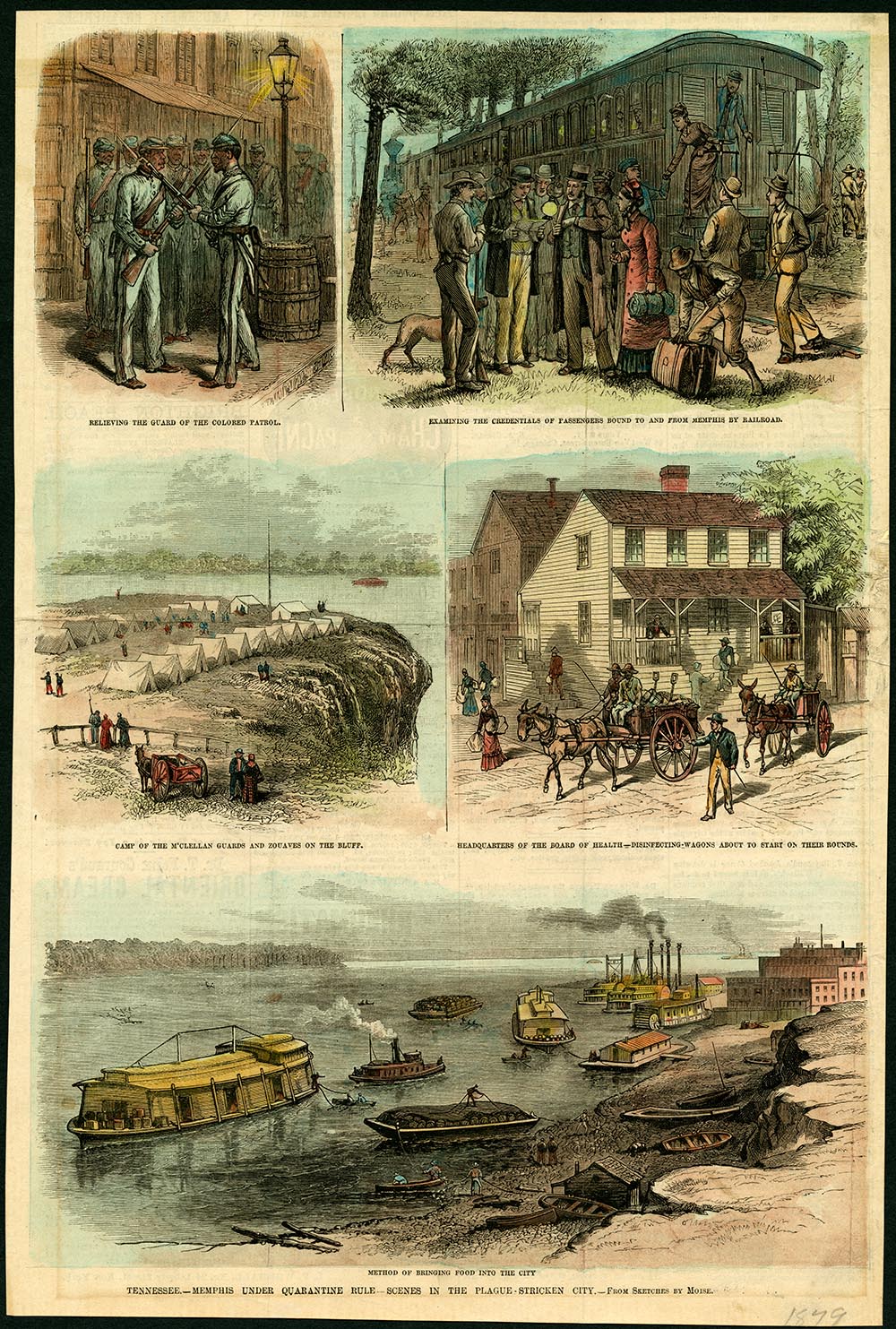

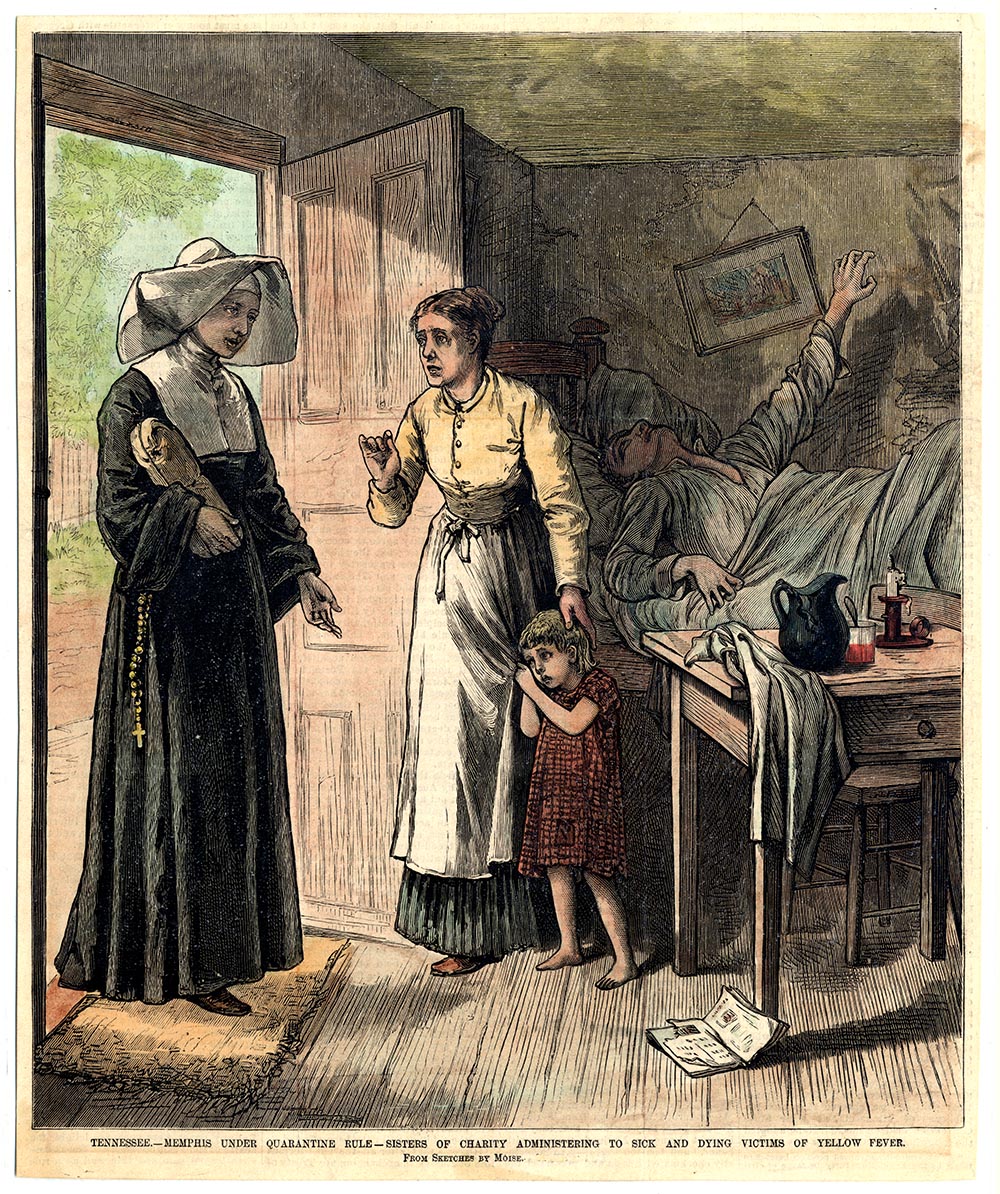

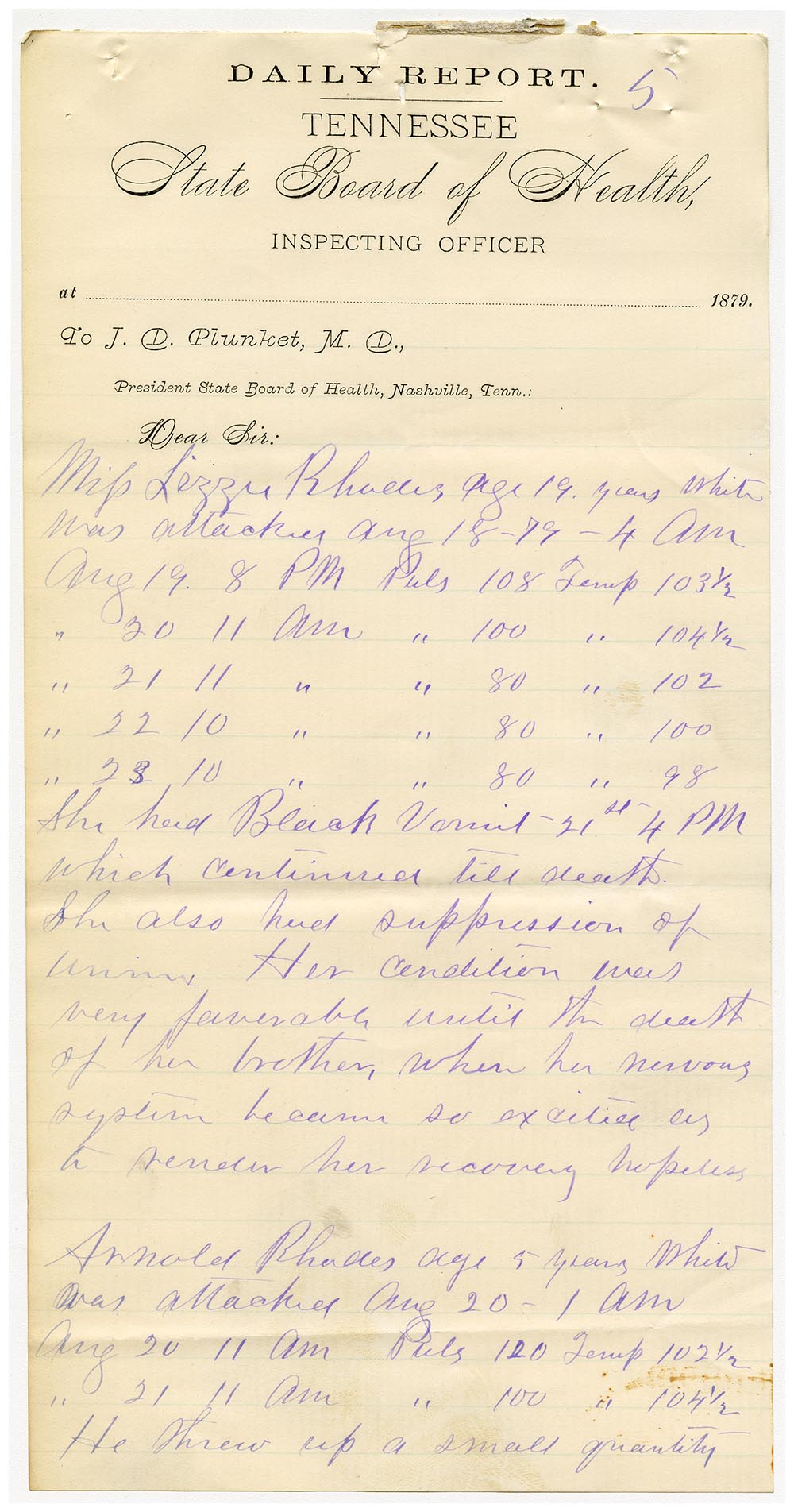

Tennessee had begun to recover from the devastation of the Civil War. Sixteen percent of the state’s two million people lived in cities in 1900, with the largest city, Memphis, having a population of 102,300. Memphis had survived three separate outbreaks of deadly yellow fever during the 1870s. Yellow fever is spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Memphis was especially vulnerable to yellow fever because its poor sanitation and drainage systems gave the mosquitoes many places to breed. During the 1878 outbreak, most of Memphis’s wealthy citizens fled, and the city almost ceased to function. Many brave doctors, nurses, nuns, and priests remained in the city to care for the sick, only to contract the illness themselves. The priests and nuns of St. Mary’s Cathedral who died after contracting yellow fever from their patients are known as the Martyrs of Memphis. The epidemics killed 7,750 people. A new state board of health helped the river city to overhaul its health and sanitation system which reduced the threat of future outbreaks. People and businesses flocked to Memphis in the following years.

Nashville was also proud of its development after the war. In 1897, Nashville hosted a huge celebration in honor of the state’s 100th birthday. The Tennessee Centennial Exposition showcased industrial technology and recreations of the world’s wonders including the Parthenon. The centennial was the ultimate expression of the Gilded Age in the Upper South. During its six-month run at Centennial Park, the Exposition drew nearly two million visitors to see its dazzling monuments to the South’s recovery. Governor Robert Taylor observed, “Some of them who saw our ruined country thirty years ago will certainly appreciate the fact that we have wrought miracles.”