Despite the political tensions over slavery, trade and farm wealth climbed steadily in the 1850s. To some Tennesseans, economic success confirmed the superiority of Southern agriculture—slavery and all. Planters had invested too much money purchasing slaves to willingly give up their slaves. They viewed the election of anti-slavery Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860 as a disaster. Lincoln had so little support in Tennessee that his name was not even on the ballot. Though relatively small in numbers, slaveholders exerted great influence over the political affairs of Middle and West Tennessee, and they were convinced that the time had come for a break with the North. Governor Isham Harris was also enthusiastically pro-secession and worked hard to align Tennessee with the ten states that had already seceded from the Union.

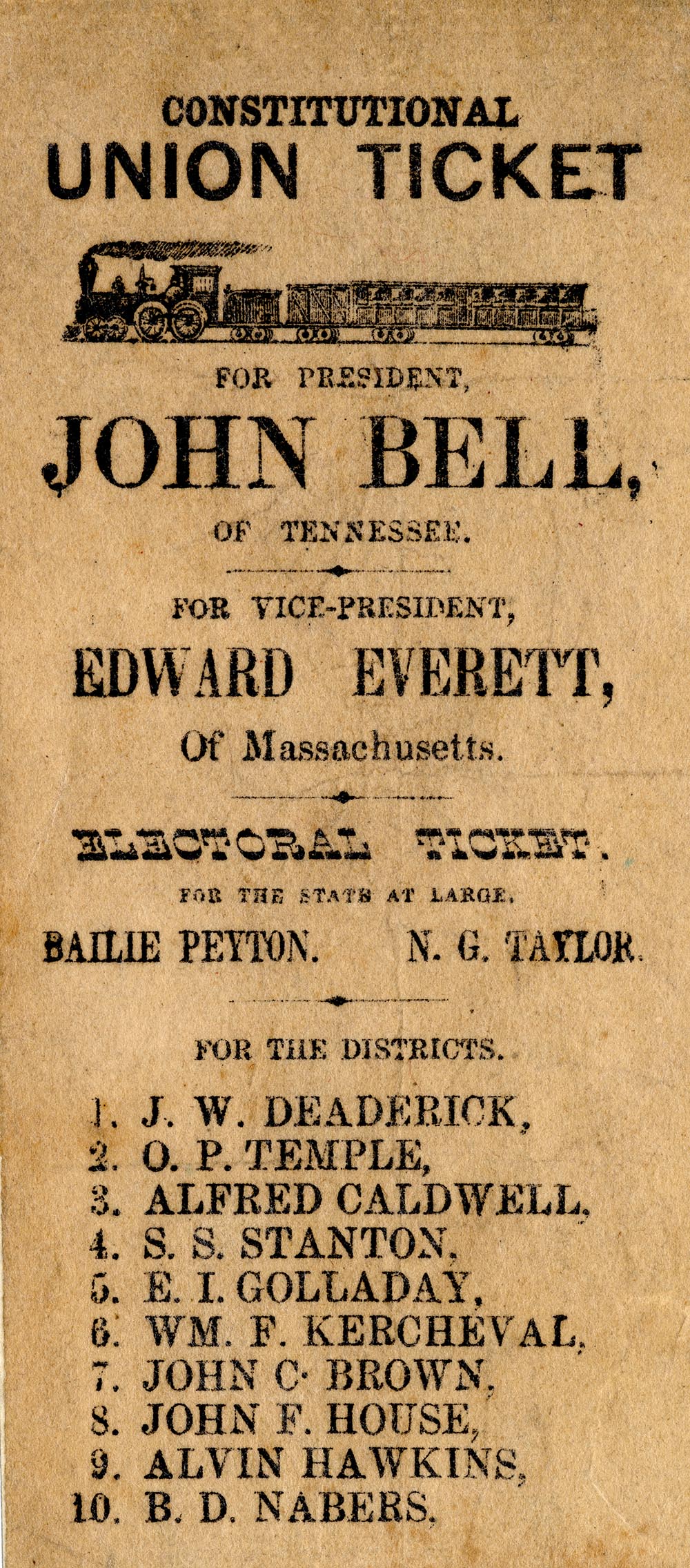

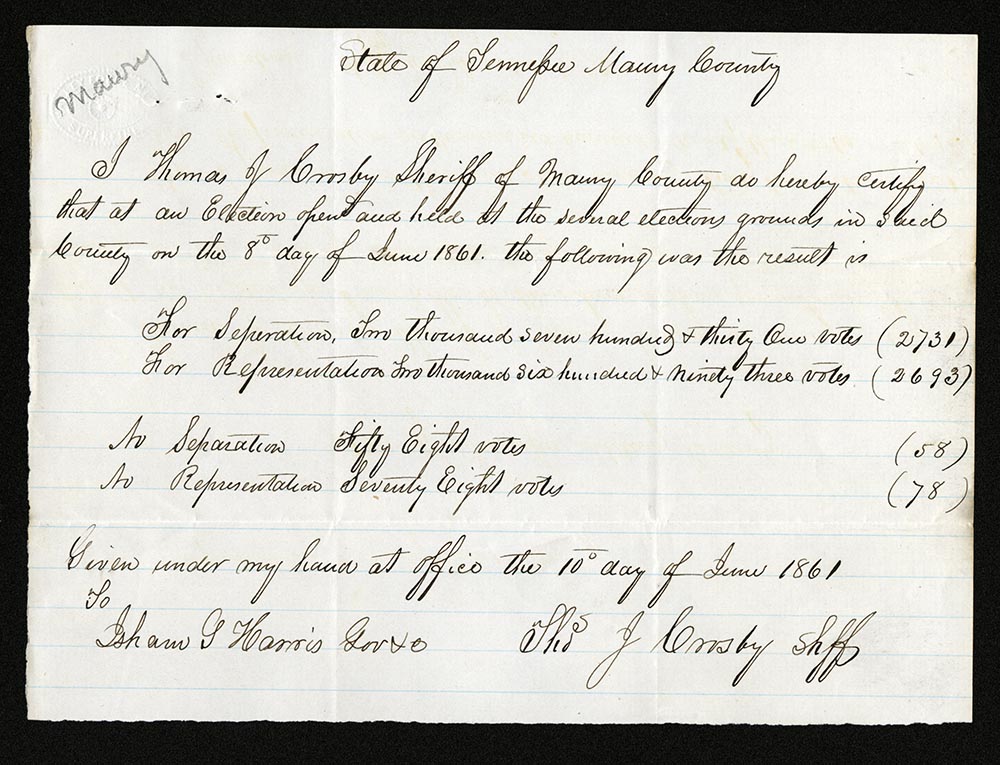

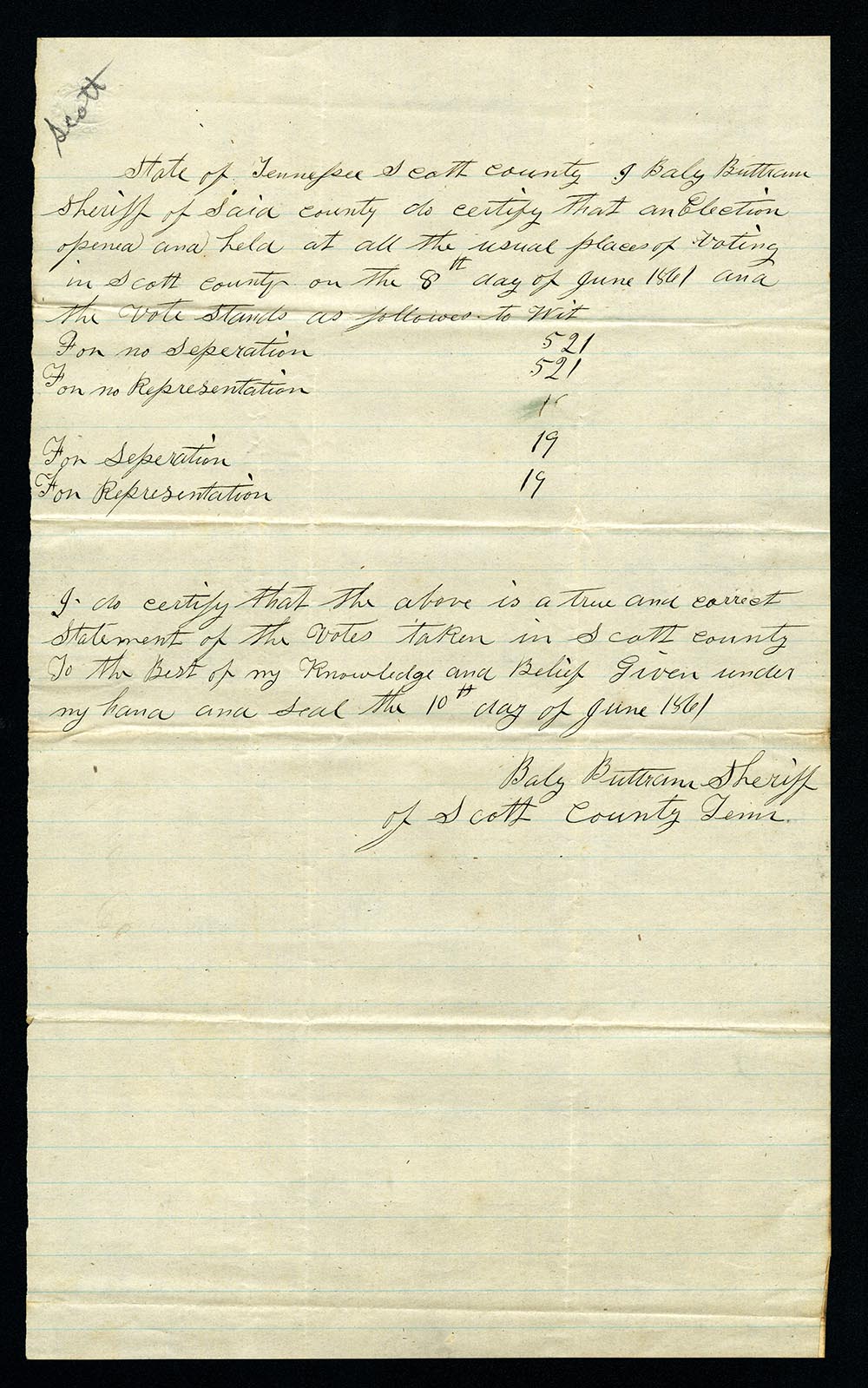

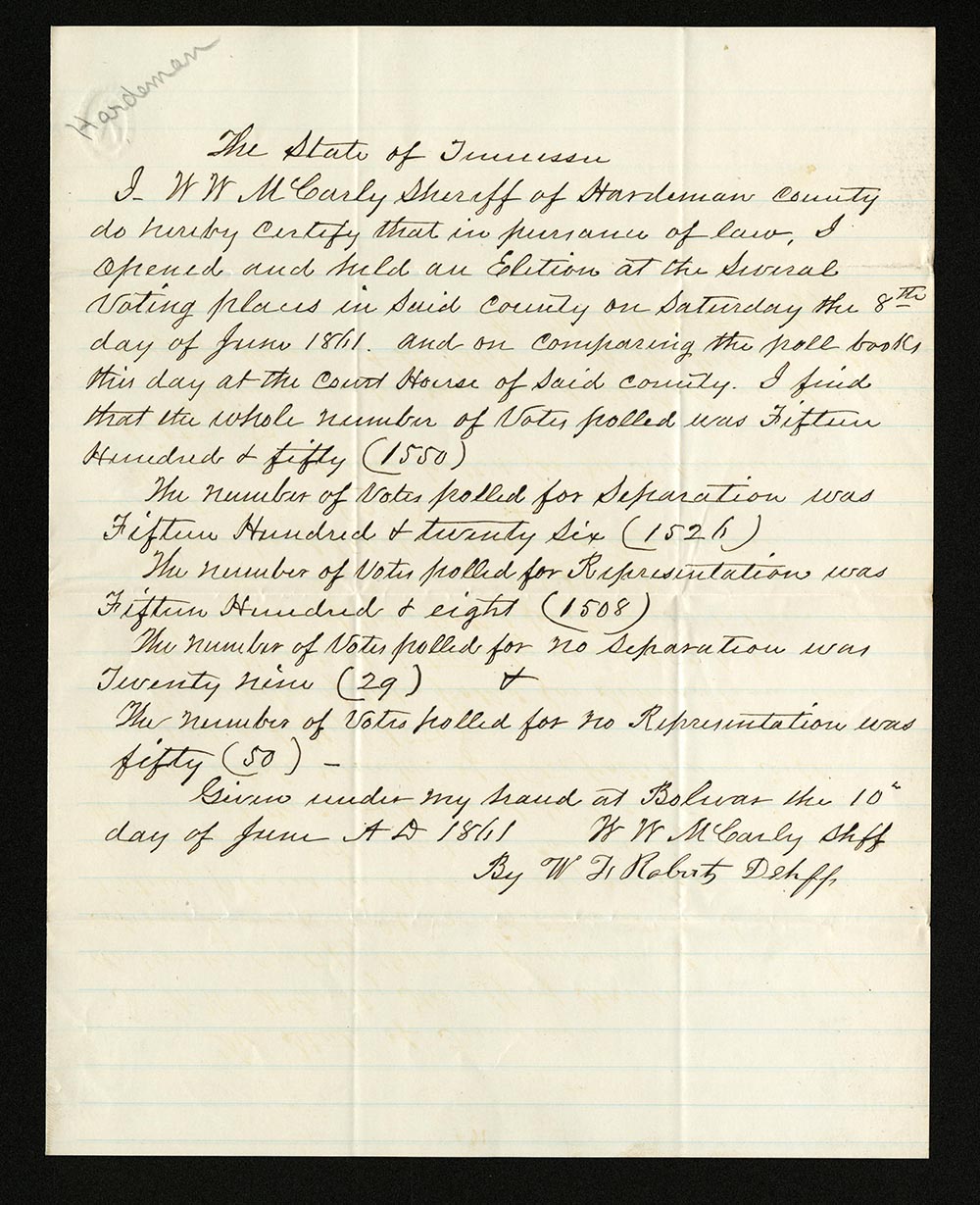

Most Tennesseans initially showed little enthusiasm for breaking away from the nation. In 1860, John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party won Tennessee’s electoral votes by a small margin. Tennessee native Bell was a moderate who wanted to find a way to keep the nation together. In February 1861, fifty-four percent of the state’s voters voted against sending delegates to a secession convention. After the firing on Fort Sumter in April, President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 troops to force the seceded states back into line. This angered many Tennesseans who refused to go along with a military invasion of the South. Governor Harris began raising troops, contacted the Confederate government, and submitted an ordinance of secession to the General Assembly. In a June 8 vote, East Tennessee held firm against separation, while West Tennessee overwhelmingly voted for secession. The big shift came in Middle Tennessee, which went from fifty-one percent against secession in February to eighty-eight percent in favor in June. Tennessee became the last state to withdraw from the Union. War was inevitable.

While Tennesseans on both sides of the conflict acted heroically, the fact remains that this was the worst of times for Tennessee and its people. Families across the state endured hardship and loss throughout the conflict. For most Tennesseans, the period from 1861–1865 was a brutal time when death and ruin ruled the land. Tennessee sent large numbers of men to fight on both sides of the Civil War. One Confederate soldier, Sam Watkins, would later write about his experiences as a “humble private” in a memoir titled Company Aytch. Tennessee provided 187,000 soldiers for the Confederacy and 51,000 soldiers for the Union. Tennessee’s divided loyalties were evident throughout the state. Rival recruiters signed up Johnny Rebs, or Confederate soldiers, and Billy Yanks, or Union soldiers, just a few blocks from each other in Knoxville. Unionist Scott County declared itself to be the Free and Independent State of Scott. In McNairy County, Unionist Fielding Hurst organized mounted soldiers to aid the Union and protect the area known as “Hurst Nation” from guerrilla attacks. Guerrilla fighters use ambushes, sabotage, and hit-and-run tactics to attack larger armies or other groups of guerrilla fighters.

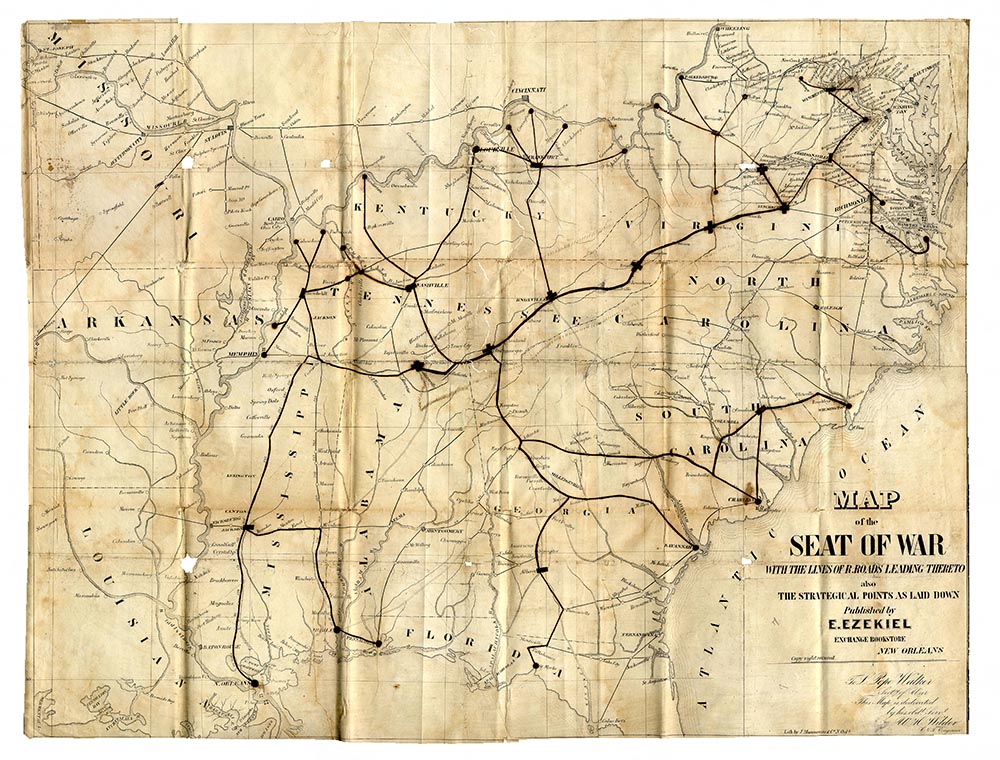

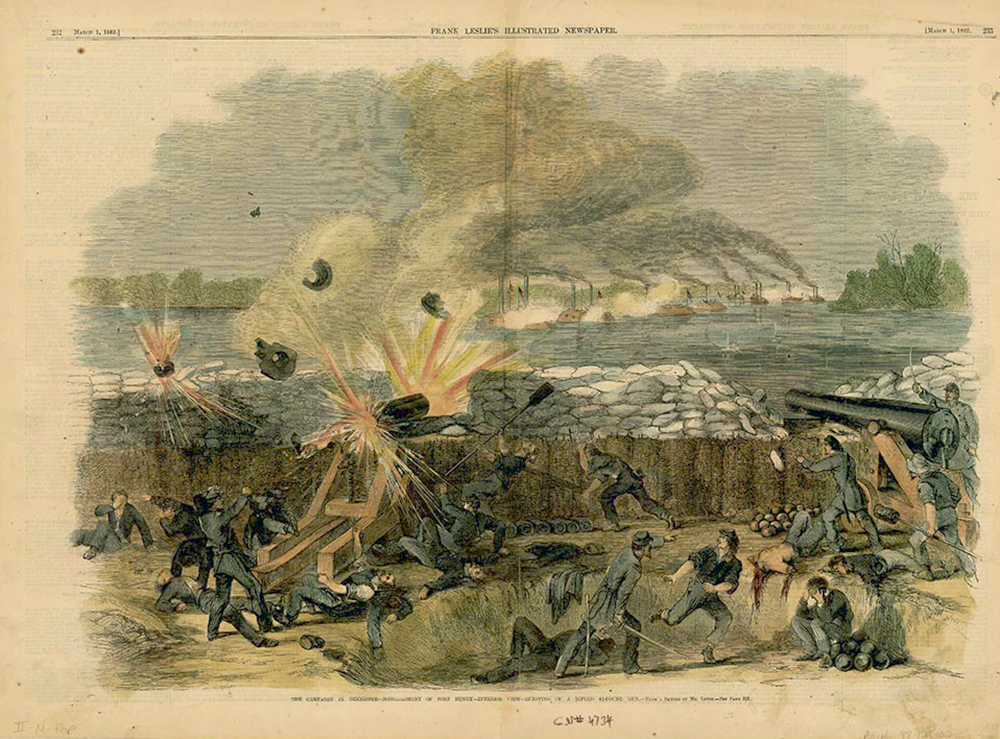

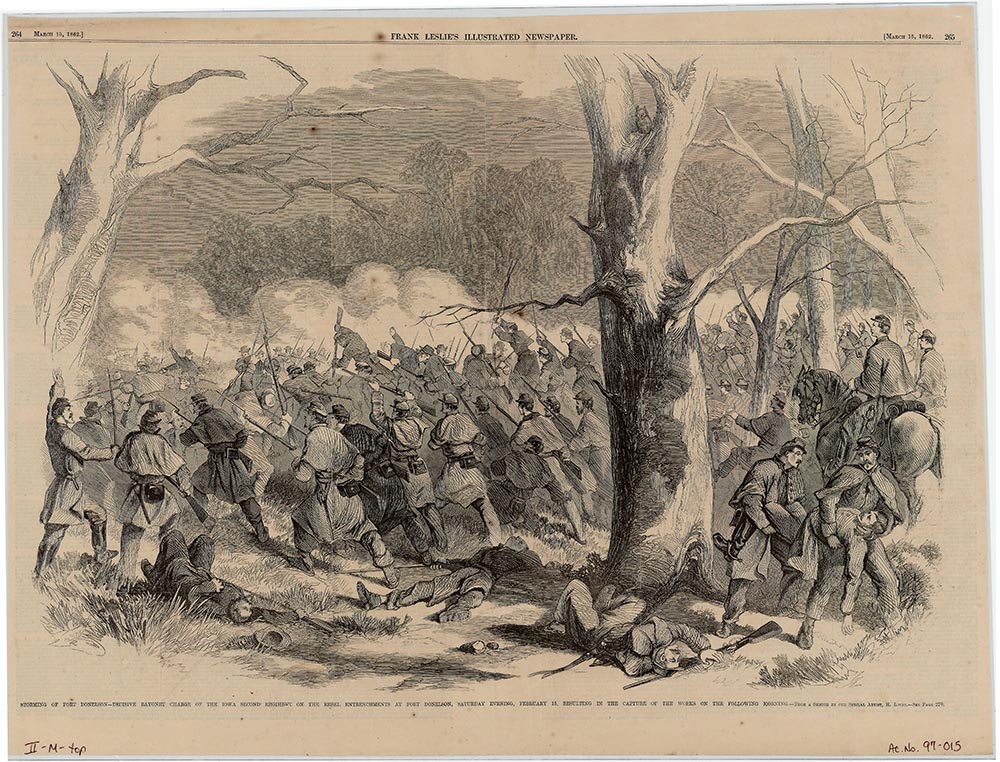

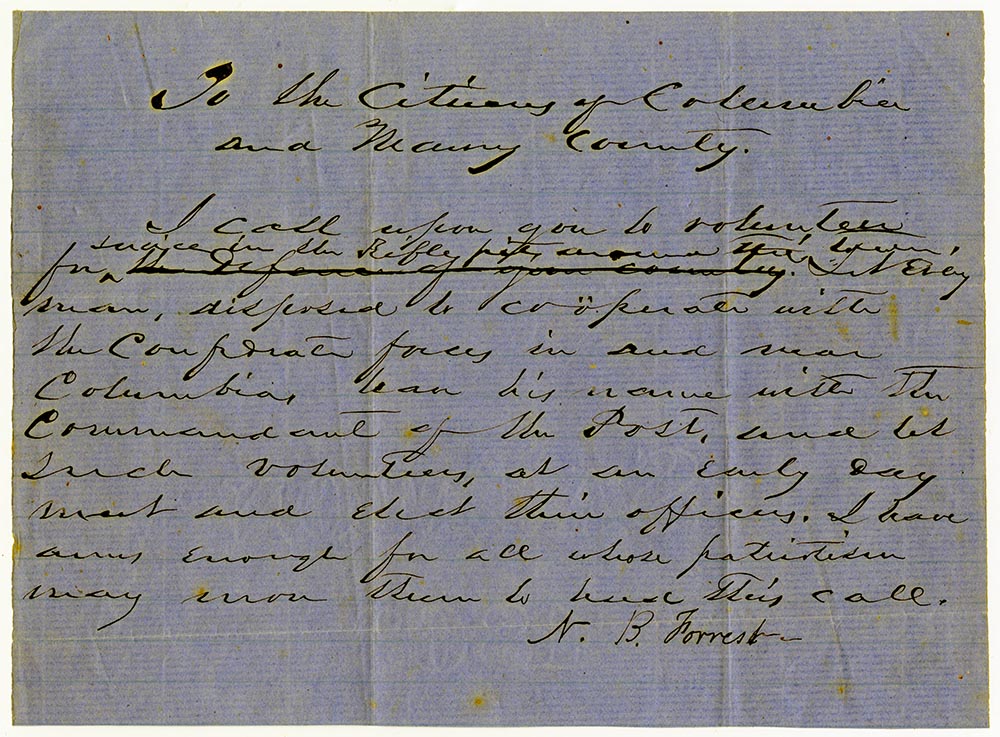

The troops that Governor Harris turned over to the Confederate government became the basis of the Confederacy’s main western army, the Army of Tennessee. While a few Tennessee Confederates were sent east to Lee’s army, most of Tennessee’s Confederate soldiers fought on their home soil. As a result, the Confederate Army of Tennessee fought particularly hard against the better-armed and more numerous Union army. Confederate Commander Albert Sidney Johnston set up a defensive line from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River. The Union high command, however, recognized that Tennessee’s rivers could serve as natural pathways for invading the South. The weakest points were Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. In late January 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant and Commodore Andrew Foote steamed up the Tennessee River with seven gunboats and 15,000 troops to attack Fort Henry. Union gunboats quickly defeated the half-flooded fort. While Foote’s boats came back around to the Cumberland River, Grant marched his army overland to lay siege to Fort Donelson. A siege is a military operation in which an enemy surrounds a fort or town and cuts off essential supplies. The Confederate guns there were more than a match for the Union gunboats. Though the Confederates had a good chance at breaking through the siege, three generals decided to surrender on February 15, 1862. Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest refused to surrender and managed to lead some troops out of the fort. Approximately 10,000 Confederate soldiers were surrendered and packed off to Northern prison camps.

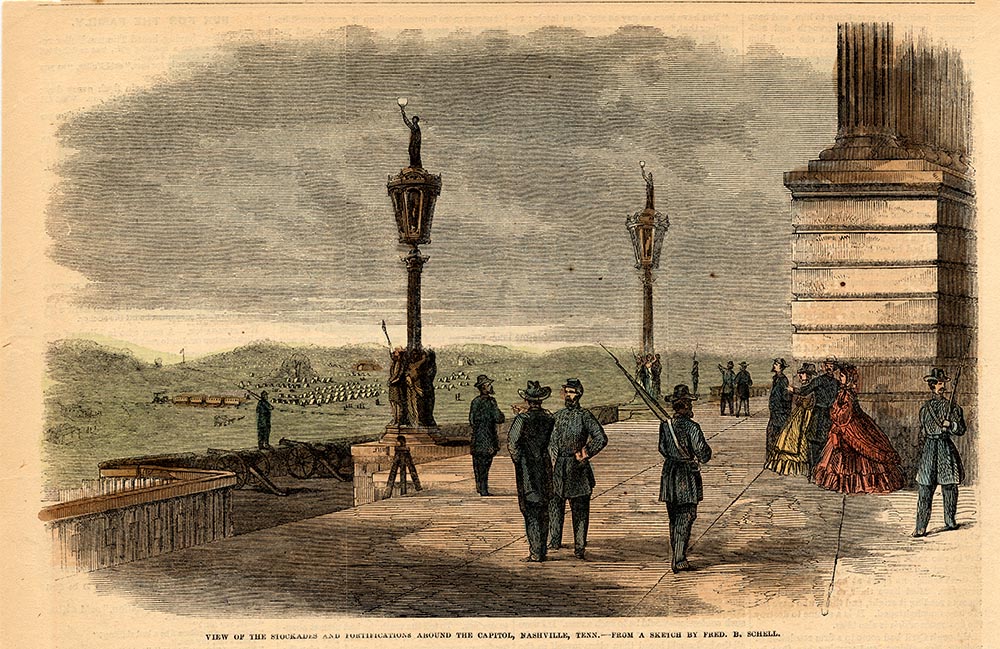

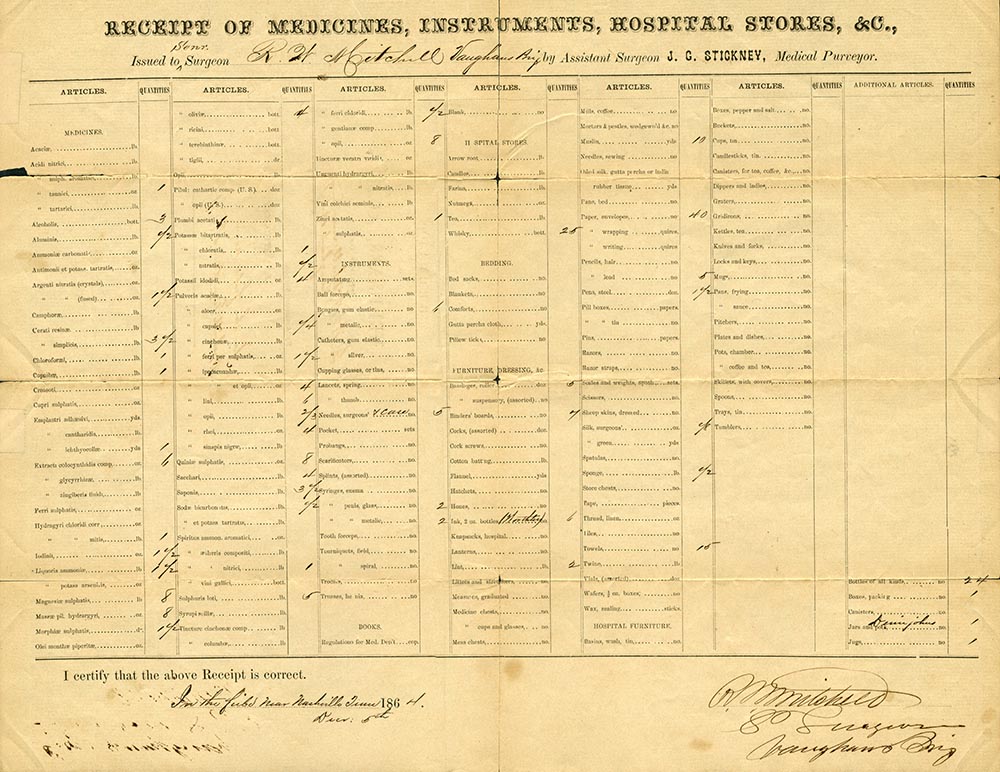

The loss of Fort Donelson was the first real catastrophe for the Confederacy. In a show of force, Foote sent the gunboats steaming up the Tennessee River into Alabama. The rivers that had been so valuable to Tennessee before the war now became routes by which Union forces captured the region’s towns and cities. Nashville had been left undefended except for two weak forts. Union troops captured the city on February 24, 1862, as frightened residents streamed southward out of the city. The loss of Nashville and Middle Tennessee was a huge blow to the Confederate war effort. The Confederacy had lost one of its chief manufacturing centers, tons of badly needed supplies, and one of its richest farm regions. Nashville remained in Union hands until the end of the war, sparing it the destruction suffered by other Southern cities. The city would serve as the headquarters, supply depot, and hospital center of the Union command in the West.

The retreat of Confederate forces to Mississippi left West and Middle Tennessee occupied by enemy troops, a harsh condition that soon stirred up resistance from civilians. Vicious behind-the-lines warfare broke out between Confederate guerrillas and Union troops. There was widespread fighting in East Tennessee between Unionist and Confederate sympathizers. The breakdown of civil order offered many opportunities for settling old scores. Houses were burned, property was stolen, and lives were taken by bands of armed men who roamed the countryside. Guerrilla warfare was particularly brutal on the Cumberland Plateau where Confederate guerrilla Champ Ferguson and Unionist “Tinker” Dave Beaty were responsible for many deaths.

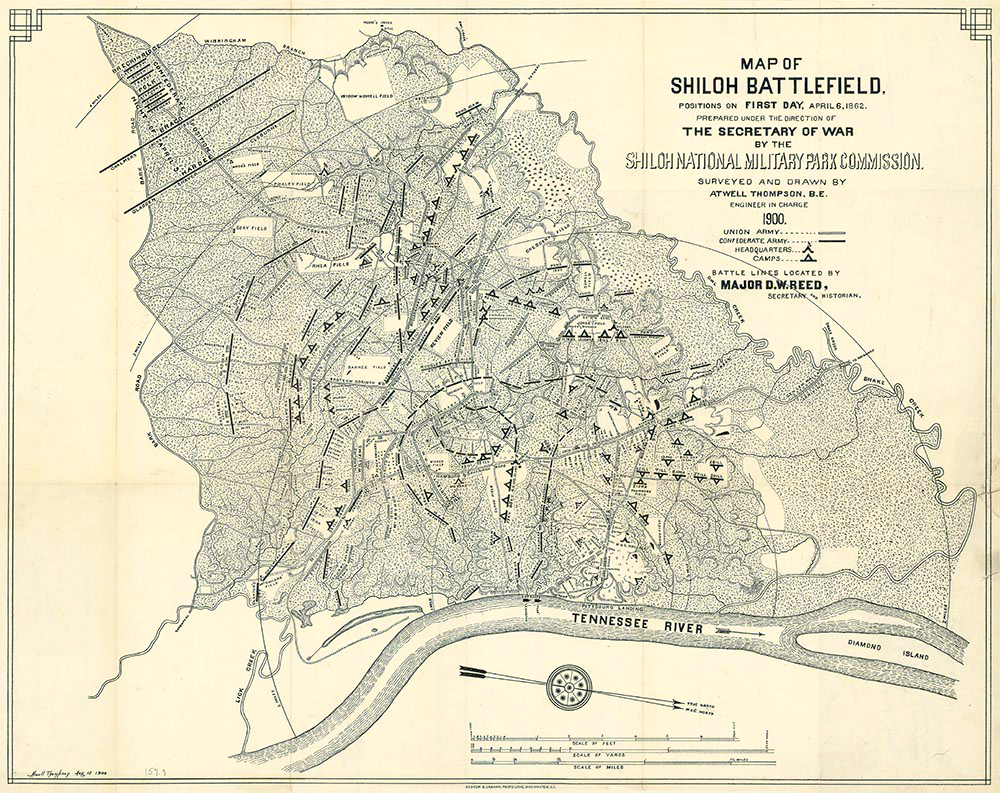

In April 1862, General Johnston’s army attacked Grant’s troops near Shiloh Chapel in Hardin County. The two forces were of roughly equal size, but the Confederates seized the advantage. By evening, they had nearly driven Grant’s men to the Tennessee River but did not deliver the knockout blow. The fighting cost the lives of many men, including General Johnston himself. During the night, 25,000 fresh Union troops reinforced Grant’s battered troops, allowing him to mount a strong counterattack the next day. The weary Confederates, now under the command of General P.G.T. Beauregard, were forced to withdraw that evening. Shiloh was a bloody wake-up call for the nation. More men were lost in the Battle of Shiloh than in all of America’s previous wars, and both sides began to realize that the war would be long and costly.

Tennessean David Farragut’s capture of New Orleans in late April was an important step in the Union’s plan to control the entire Mississippi River. Another important port city on the Mississippi came under Union control when Memphis surrendered on June 6, 1862. Middle and West Tennessee were entirely under Union control. Ironically, only pro-Union East Tennessee remained in Confederate hands. Governor Harris and the state government, which had moved to Memphis after Nashville’s fall, were forced to flee the state altogether. In its place, President Lincoln appointed former Governor Andrew Johnson to be military governor. A loyal Greeneville Unionist, he had kept his seat in the U.S. Senate despite Tennessee’s secession. Johnson introduced a new political order to Union-occupied Tennessee. Johnson wanted to return the state to the Union as soon as possible by favoring the Unionist minority and suppressing the pro-Confederate crowd. Johnson was unpopular and was often forced to use Union troops to enforce his orders.

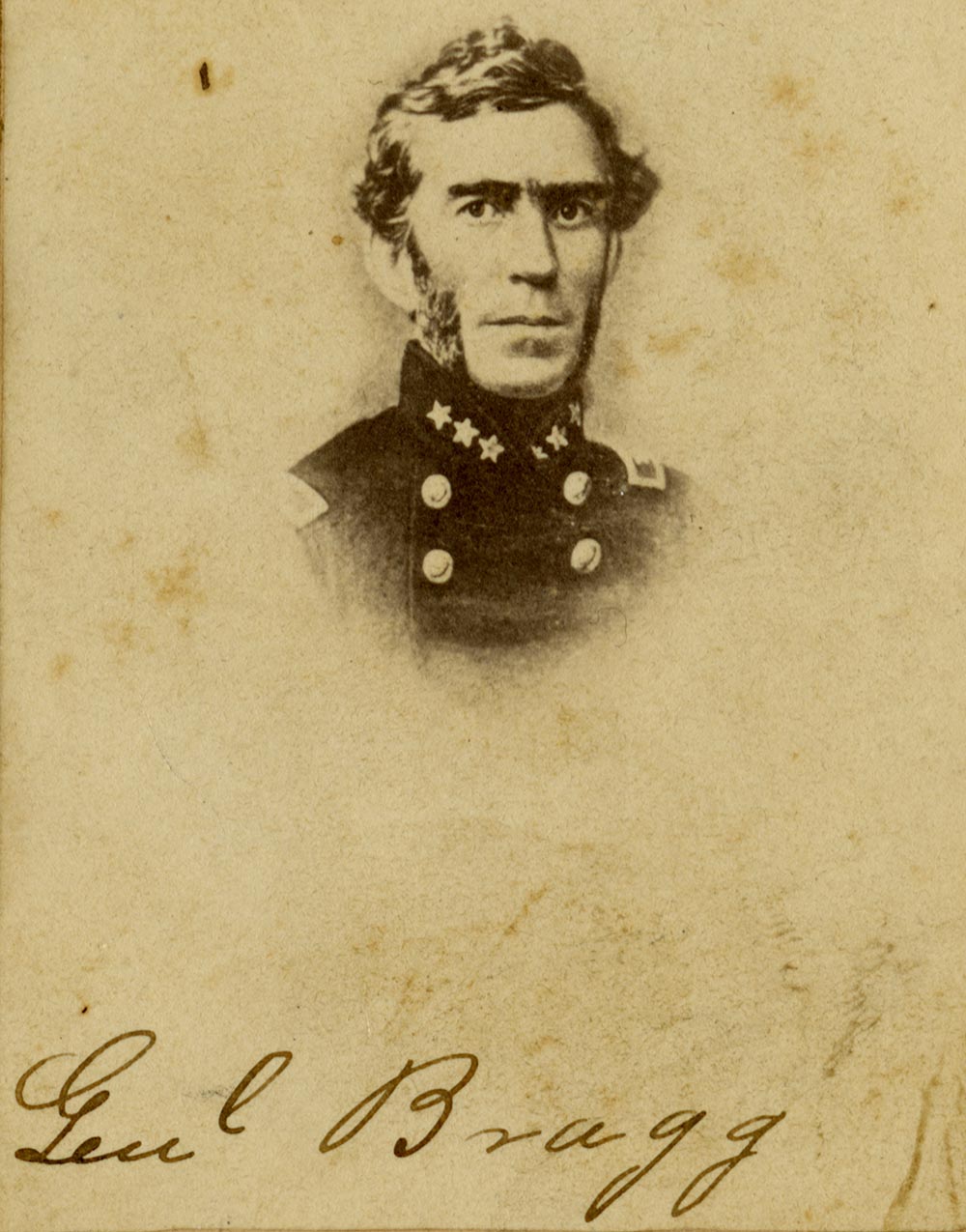

Confederate hopes were raised in the late summer of 1862, when brilliant cavalry raids by Forrest and John Hunt Morgan stopped the Union’s advance on Chattanooga and returned control of lower Middle Tennessee to the Confederates. Under the command of the quick-tempered Braxton Bragg, the Army of Tennessee advanced into Kentucky. Following the Battle of Perryville, Bragg’s army camped near Murfreesboro to await the Union’s next move. In late December, an army of 50,000 under William Rosecrans moved out from Nashville to confront the Confederates near Murfreesboro. On December 31, the Confederates drove the Union back on the first day of battle, but were stopped by the Union’s strong defensive positions. On January 2, Bragg launched a disastrous infantry assault in which the Confederates were slaughtered by Union artillery. One of every four men who fought at Stones River was killed, wounded, or missing.

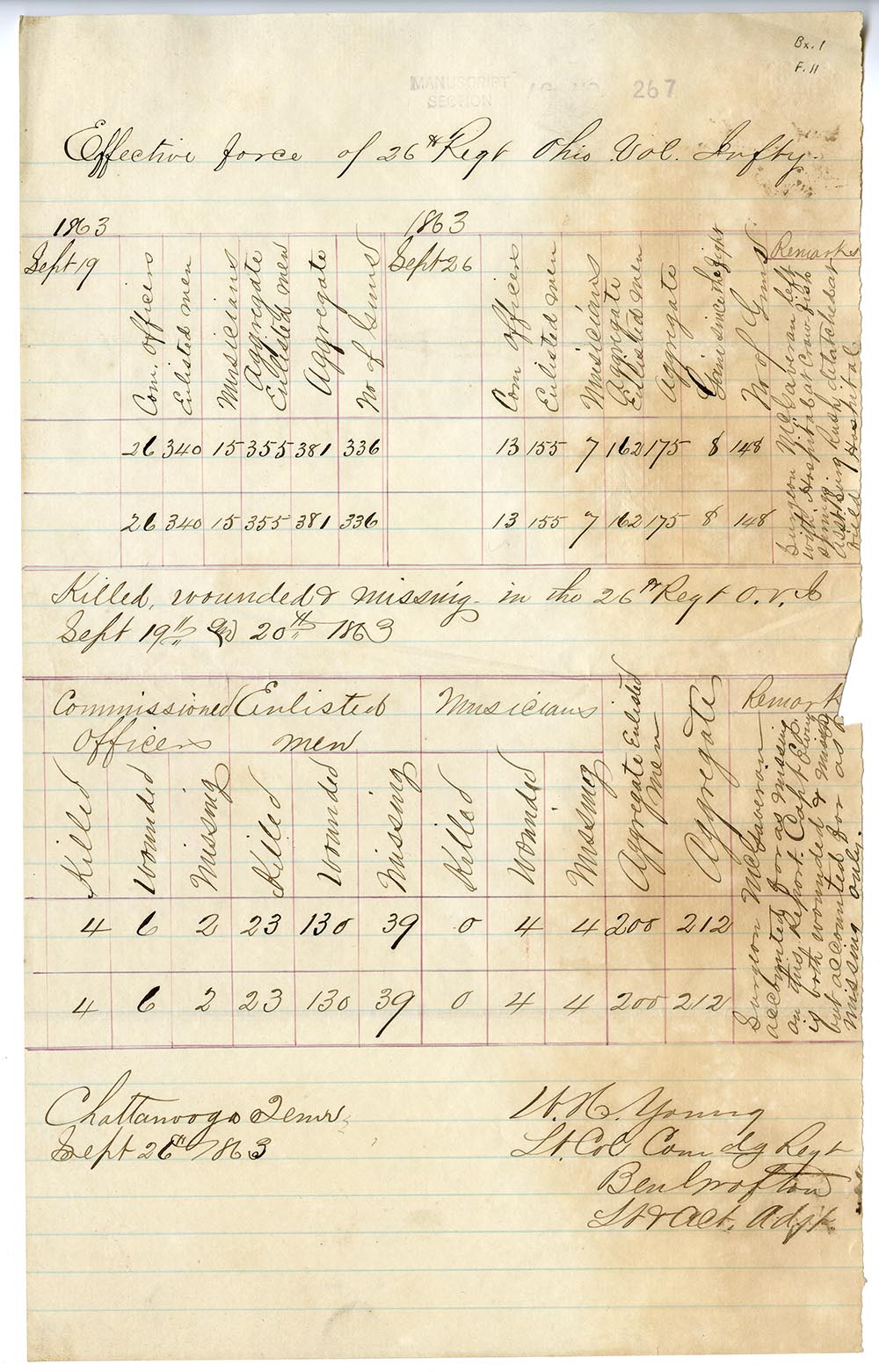

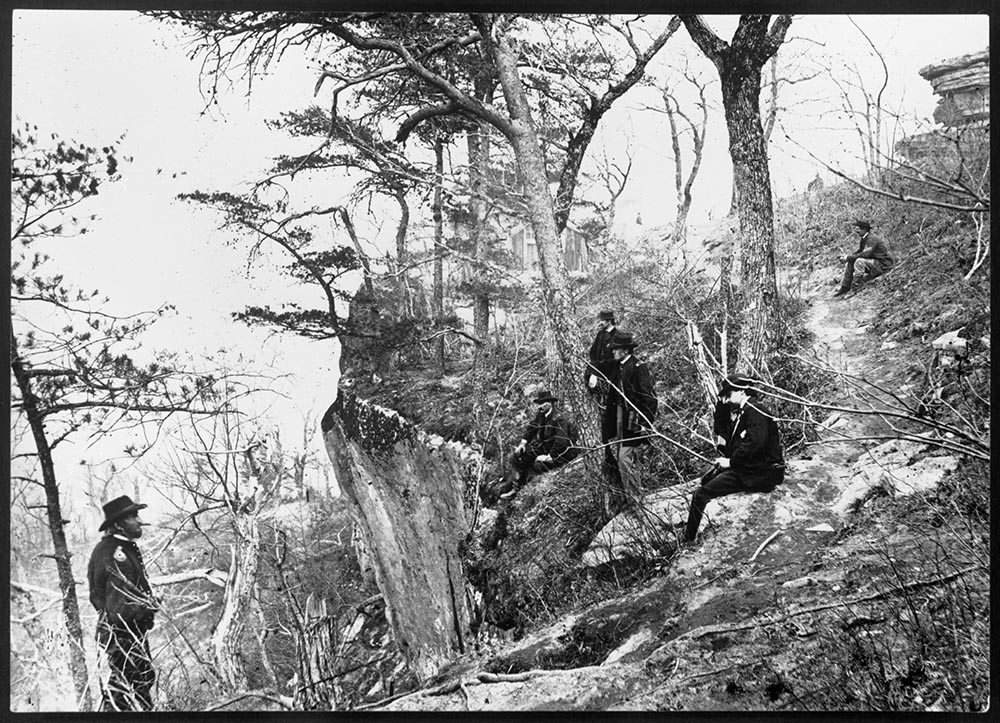

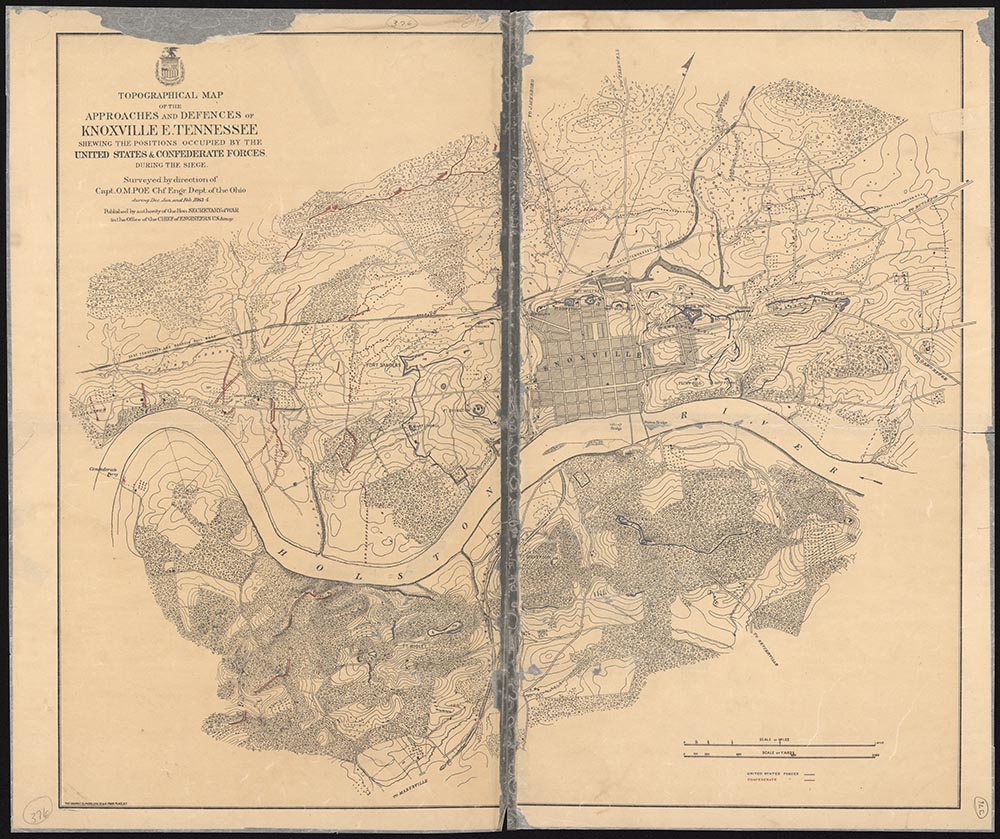

The Army of Tennessee stayed in a defensive line along Duck River until late July 1863, when Rosecrans maneuvered Bragg into abandoning the vital rail center of Chattanooga and retreating into North Georgia. The overconfident Rosecrans stumbled into Bragg’s army along Chickamauga Creek. On September 19 and 20, the two armies fought savagely in the woods—a battle that one general compared to “guerrilla warfare on a grand scale.” On the second day, part of Bragg’s force poured through a gap in the Union line and nearly defeated Rosecrans’s army. General George Thomas earned the nickname the “Rock of Chickamauga” by stopping the Confederate advance and allowing the rest of Rosecrans’s army to escape. Bragg won a great victory at Chickamauga but at a frightful cost (21,000 casualties out of 50,000 troops), and he again failed to follow up his success. The Union troops dug in around Chattanooga, while the Confederates occupied the heights above the town. Grant hurried to Chattanooga to take charge of the situation, and, on November 25, his troops drove Bragg’s army off Missionary Ridge and back into Georgia. It would be nearly a year before the Confederate army returned to Tennessee.

At the same time that Bragg abandoned Chattanooga, a Union force under Ambrose Burnside captured Knoxville. The whole state was now in Union hands. Local citizens were burdened by the constant requisitions of food, grain, and livestock. A requisition is an official order to claim property for military use. Adding to the problem, undisciplined troops stole anything that could be eaten from local citizens. Being forced to supply both the Union and Confederate armies caused more destruction and loss of property in Tennessee than actual combat.

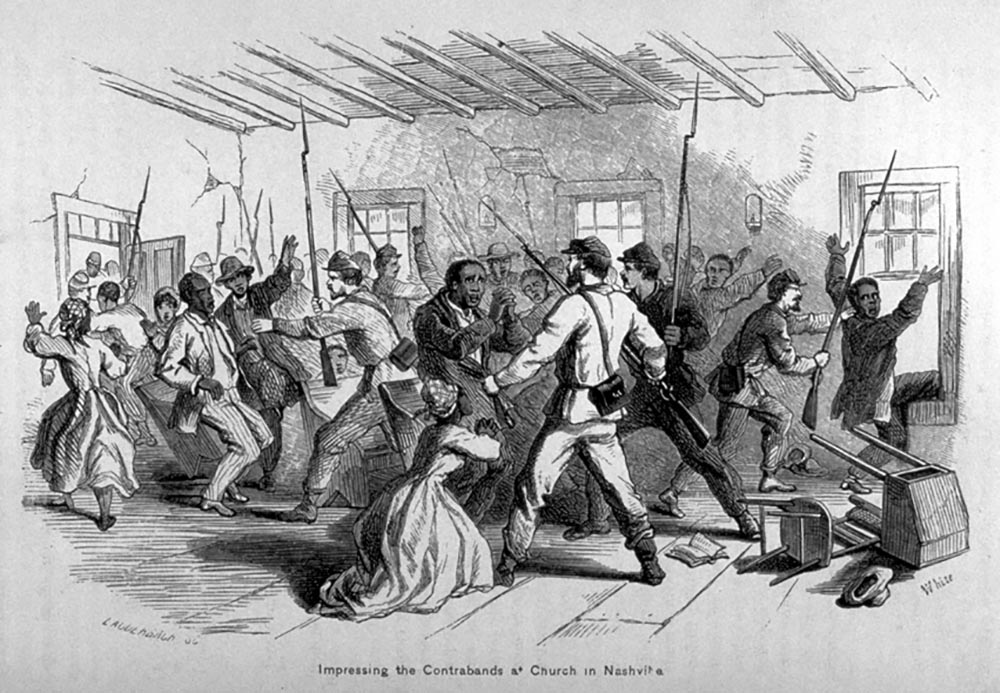

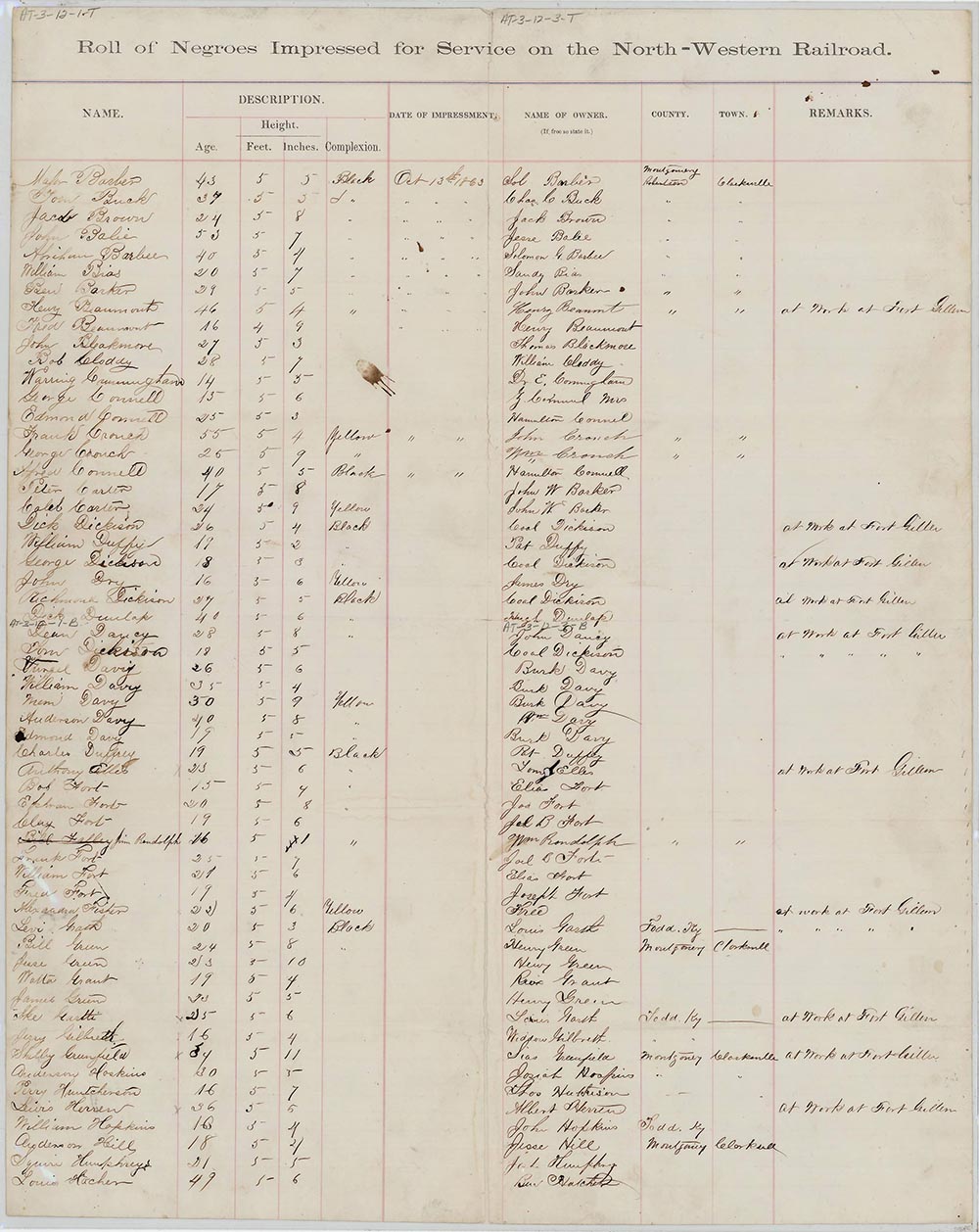

The war brought a sudden end to slavery. African Americans rejoiced in their freedom but were uncertain about their future in Tennessee. The system of plantation discipline and slave patrols began to break down early in the war. Union commanders organized “contraband” camps to accommodate the large numbers of fugitive, or runaway, slaves who streamed into Union camps. The Union impressed, or forced, African Americans from the contraband camps into service as laborers. The men built railroads, bridges, and forts throughout Tennessee. Missionaries and sympathetic Union officers provided education for people in the camps. They also arranged for some ex-slaves to work for wages on military projects. Hiring African Americans to work for the U.S. government helped former slaves to transition from being unpaid laborers to freedmen. In late 1863, the Union army started recruiting men to serve in “colored regiments.” The call was answered by 20,133 Tennesseans. These men made up forty percent of Tennessee’s Union recruits. African Americans in Tennessee gained citizenship and the right to vote earlier than other African American Southerners partly because of their record of military service.

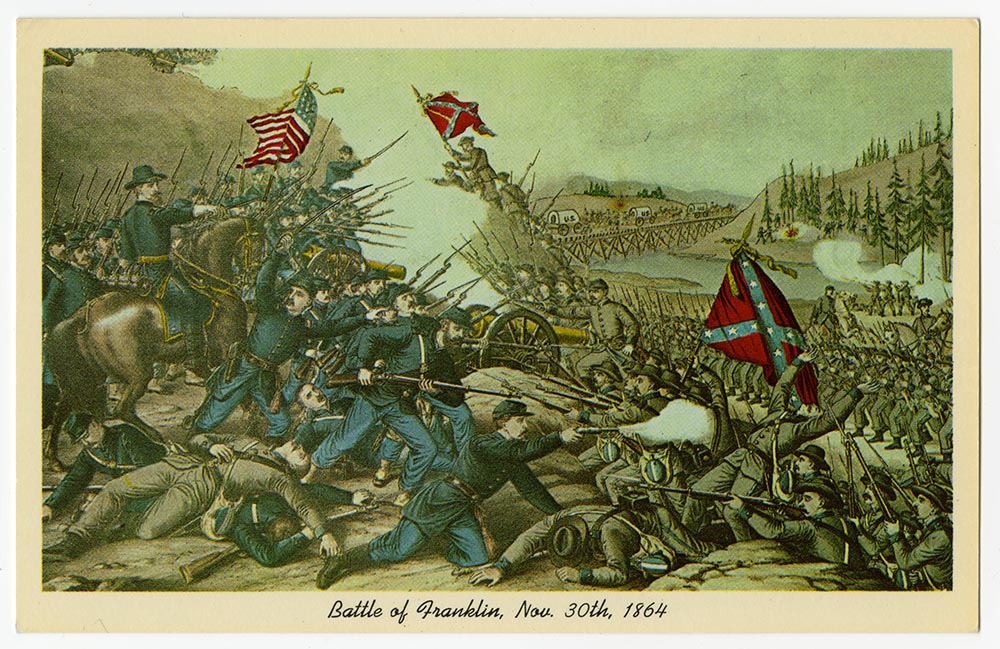

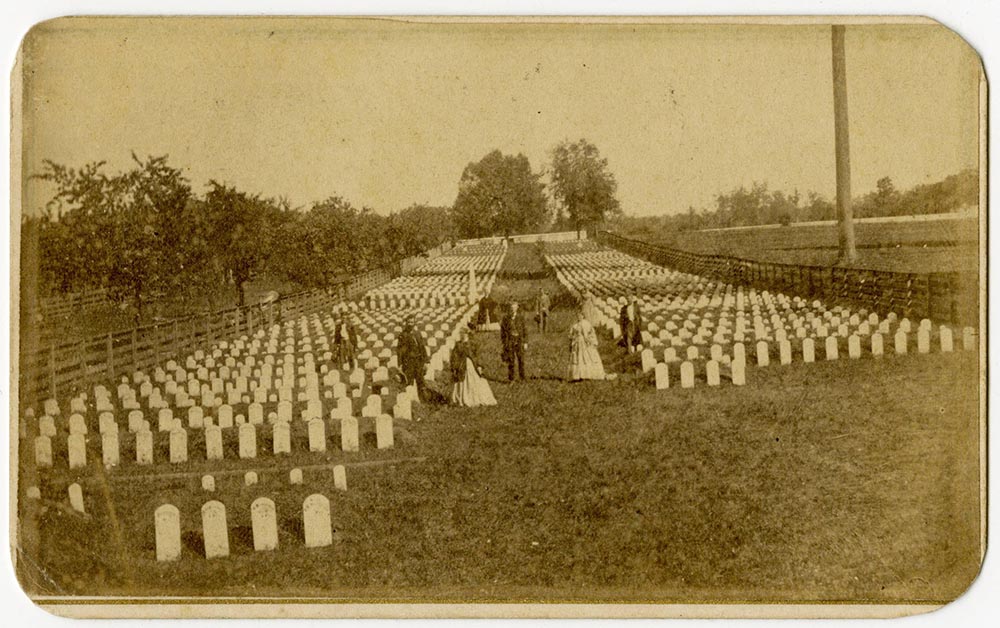

In the fall of 1864,William T. Sherman’s army captured the city of Atlanta. This convinced John Bell Hood, commander of the Army of Tennessee, to take bold action. Hood wanted to draw the Union out of Georgia by threatening Nashville. Hood’s plan had little chance of success, but the Confederacy’s situation was desperate, and Hood was desperate for glory. The Tennessee troops were in high spirits as they crossed into their home state. They would meet the Union army at Franklin on November 30, 1864. On Hood’s orders nearly 20,000 men charged across an open field towards Union troops protected by temporary defenses made of earth and tree branches. As regiment after regiment hurled itself against the Union line for five ferocious hours, 1,750 Confederate soldiers were killed. Hood’s recklessness had destroyed the Army of Tennessee. The Union retreated towards Nashville where the two armies fought again on December 15–16, 1864. The United States Colored Troops played a key role in the Union victory at Nashville. Hood’s forces managed to retreat but would never again challenge Union control of Tennessee. Although the war would continue for another four months, the Battle of Nashville effectively ended the war in Tennessee.

The Civil War had devastating effects on Tennessee. So many young men were severely wounded or killed that many young women remained unmarried in the years that followed. Planting and harvesting were extremely difficult during the war. The small amount of food that was produced during the war years was consumed by the armies. With the slaves gone, husbands and sons dead or captive, and farms neglected, many large plantations and small farms were abandoned. The economic gains of the 1850s were erased, and farm production and property values in Tennessee would not reach their 1860 levels again until 1900. On the other hand, the 275,000 Tennesseans who had been enslaved four years earlier were no longer anyone’s property. They were free at last. Others who benefited from the Civil War were the behind-the-lines profiteers who sold goods for outrageous prices. Veterans of both sides lived with the wounds and memories of the war for the rest of their lives, and the chief reward for most was a place of honor in their communities.