As the new century began, Tennessee was troubled by conflicts between the values of its traditional agrarian, or farm-based, culture and the demands of an increasingly urban world. Having lost its position of national leadership during the Civil War, the state had become somewhat isolated from the changes taking place in large cities. Tremendous intellectual, scientific, and technological innovations were sweeping America early in the twentieth century. Tennessee became a major battleground where these forces clashed with traditional ways of life. Political debates focused on issues such as Prohibition, Women’s Suffrage, religion, and education.

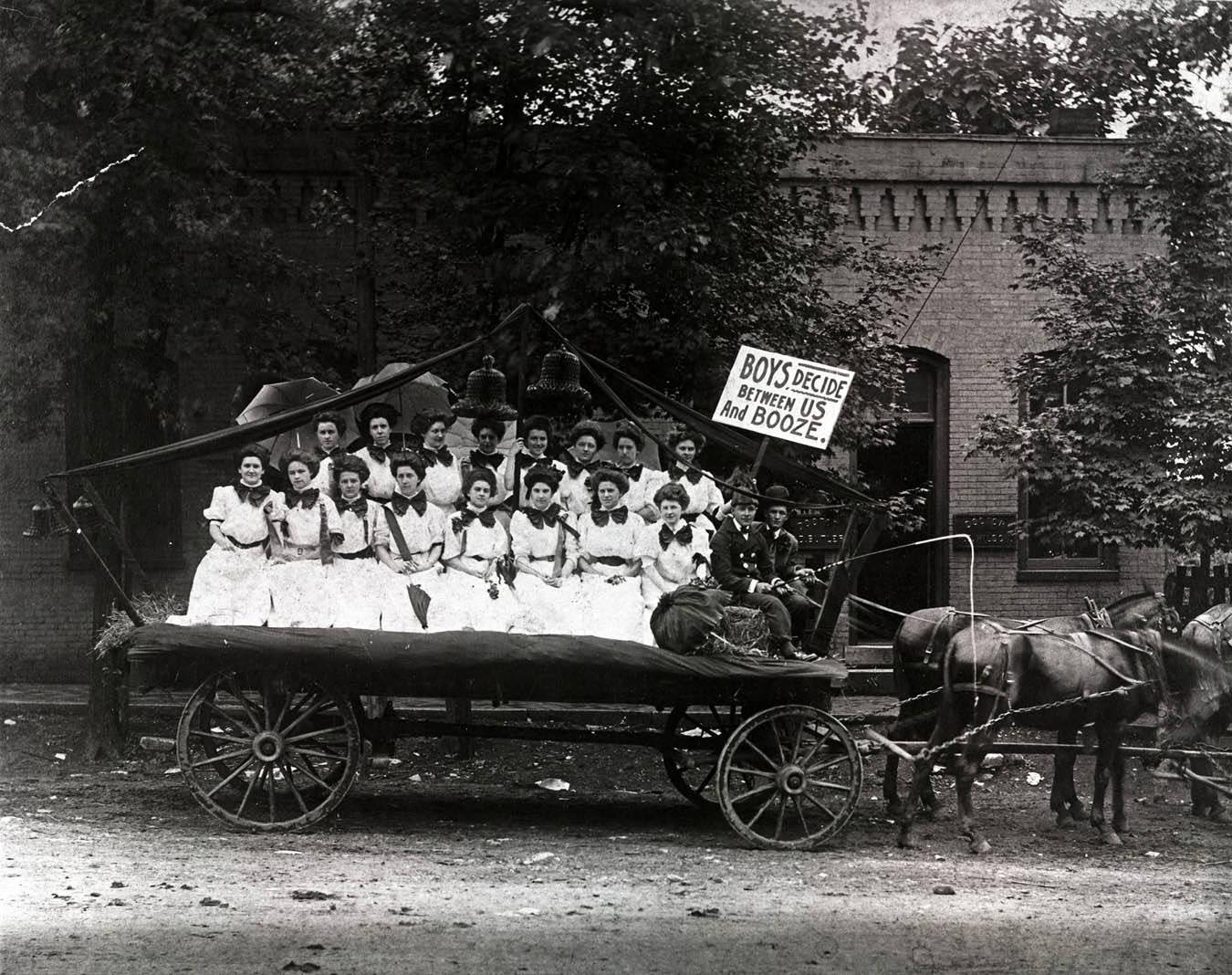

The Temperance movement originally focused on limiting the consumption of alcohol. However, by 1900 it had become a movement to prohibit liquor altogether, known as Prohibition. Tennessee had a long history of alcohol production that had continued despite the efforts of Federal agents and local sheriffs to stop it. In 1877, Temperance advocates in the General Assembly had managed to pass a “Four Mile Law,” prohibiting the sale of alcohol within a four-mile radius of a public school. Thirty years later, the liquor issue dominated the race for governor. Senator Edward Carmack, the “dry” candidate was defeated by Malcolm Patterson who opposed Prohibition. Through his newspaper, the Tennessean, the defeated Carmack waged a fierce war of words against Governor Patterson and his supporters. On November 9, 1908, the argument culminated in a gun battle on the streets of Nashville that left Carmack dead and two of the governor’s closest advisors charged with murder.

Carmack’s killing gave the Prohibition movement a martyr, in part because the man who shot him was pardoned by the governor. A martyr is a person who is killed because of his or her beliefs. Carmack’s death created the momentum to pass legislation extending the “Four Mile Law.” The new law banned liquor over virtually the entire state. Prohibitionists gained control of the Republican Party, and their candidate, Ben Hooper, won election as governor in 1910 and 1912. Tennessee remained officially “dry” from 1909 until the repeal of national Prohibition in 1933. However, the law met with considerable resistance from the mayors of Nashville and Memphis who used saloons as gathering places for the members of their political machines. Political machines are political organizations in which one person controls the politics of a city by providing supporters with jobs, city contracts, or other rewards. Statewide Prohibition was never effectively enforced, yet the issue continues today in the form of “local option” ordinances against liquor.

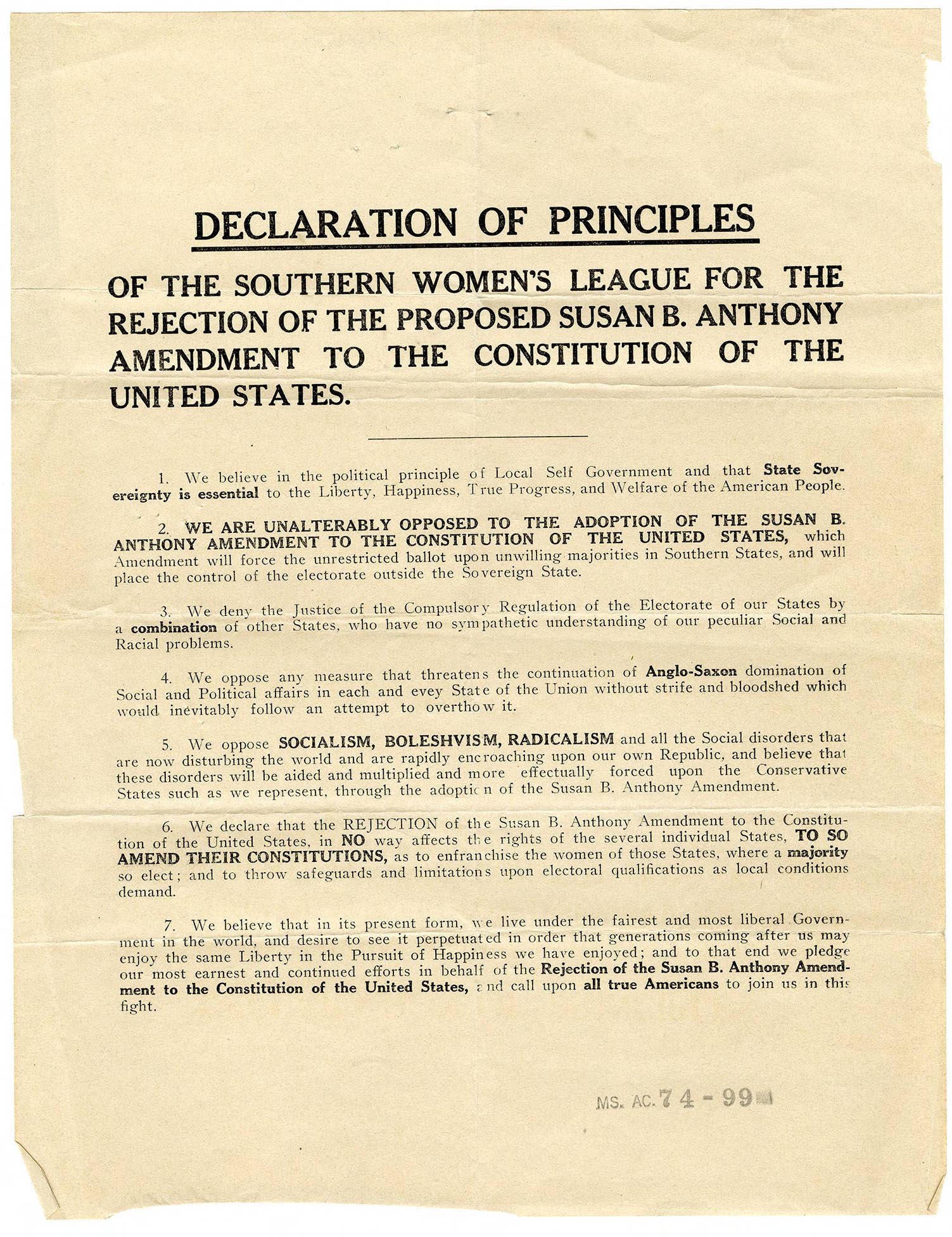

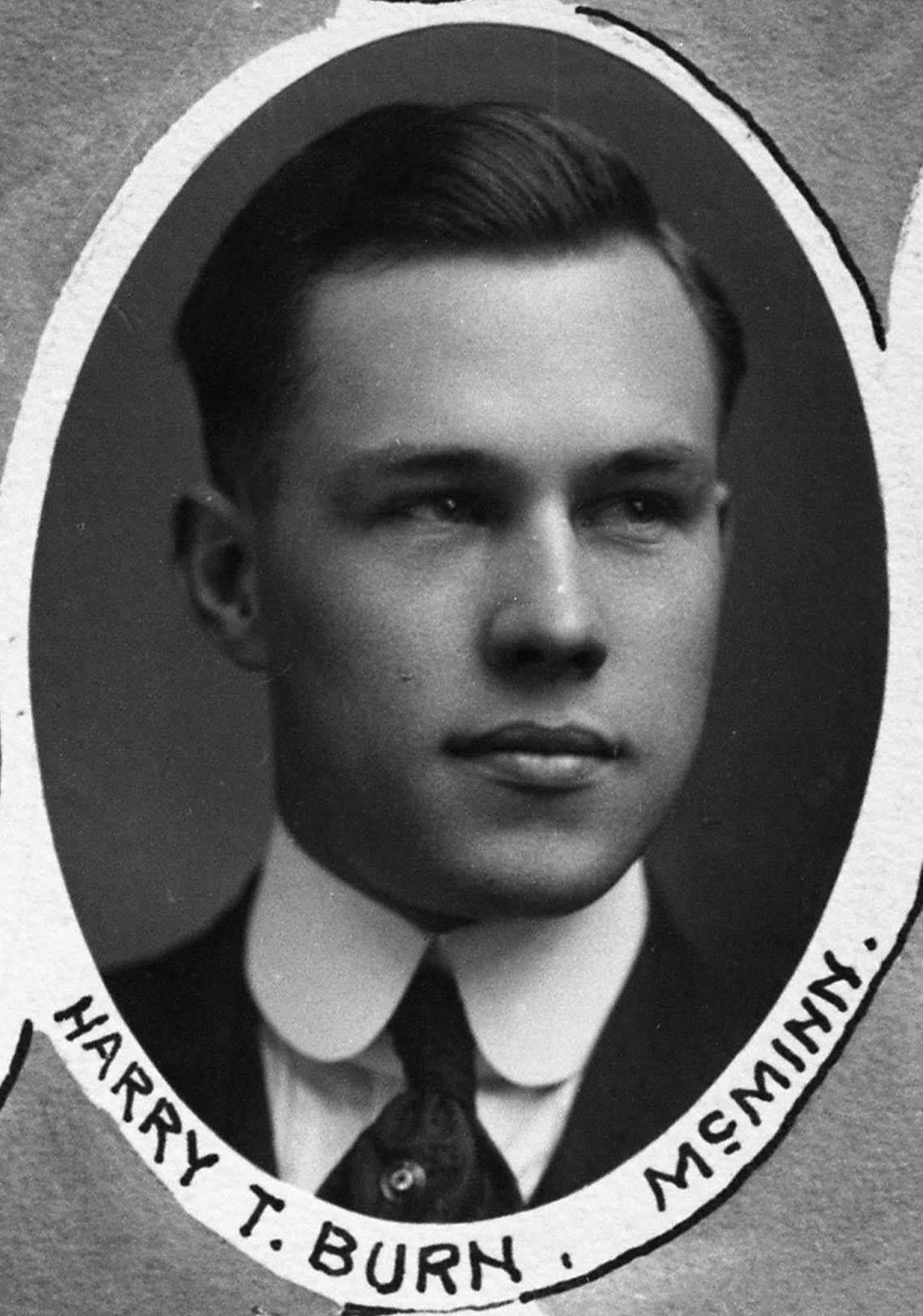

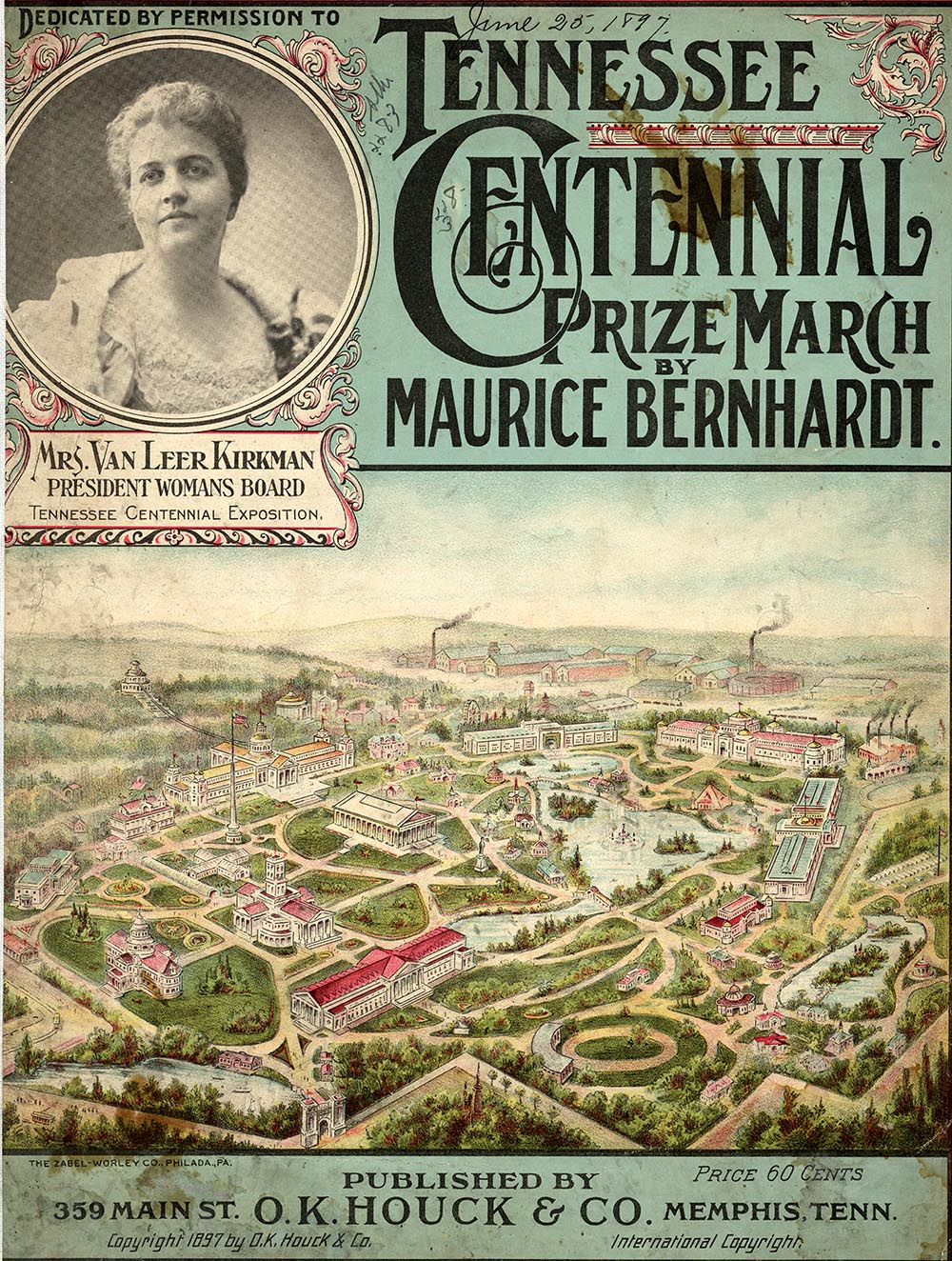

Tennessee became the focus of national attention during the campaign for Women’s Suffrage, or voting rights. Women’s Suffrage, like Temperance, was an issue with its roots in middle-class reform efforts of the late 1800s. The movement began to see success after the founding of the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association in 1906. Led by wife and mother Anne Dallas Dudley, Tennessee suffragists were able to dispel many stereotypes about themselves such as being uncaring towards their children. Anti-suffragists, led by Josephine Pearson, argued that Women’s Suffrage would bring an end to the traditional southern way of life. Despite a determined opposition, Tennessee suffragists were moderate in their tactics and gained limited voting rights in 1919. In 1920, Governor Albert Roberts called a special session of the Legislature to consider ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Leaders of the rival groups flooded into Nashville to lobby the General Assembly. In a close House vote, the suffrage amendment won passage when an East Tennessee legislator, Harry Burn, switched sides after receiving a telegram from his mother encouraging him to support ratification. With Burn’s vote, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the amendment, and Women’s Suffrage became national law. Women immediately made their presence felt by swinging Tennessee to Warren Harding in the 1920 presidential election—the first time the state had voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1868.

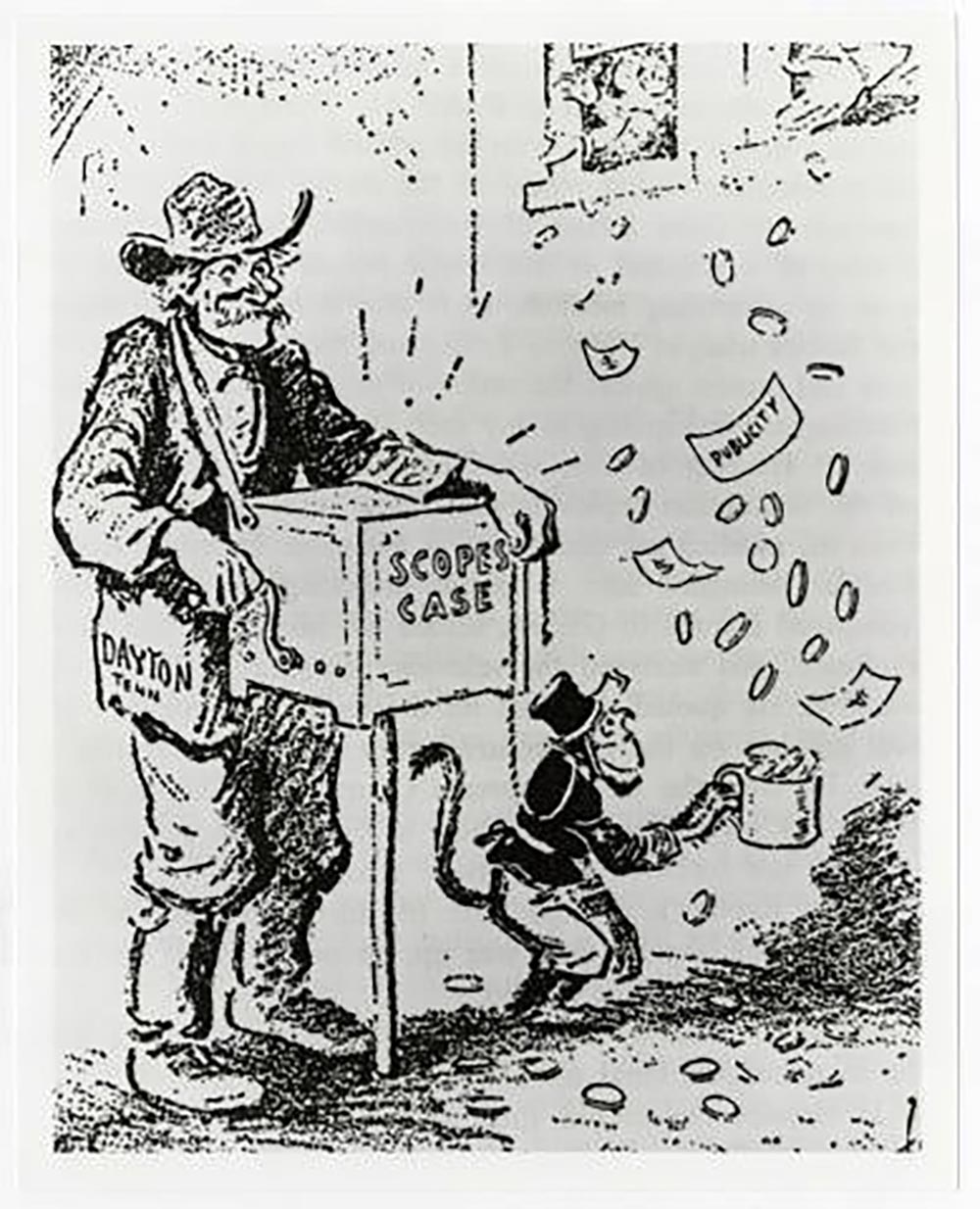

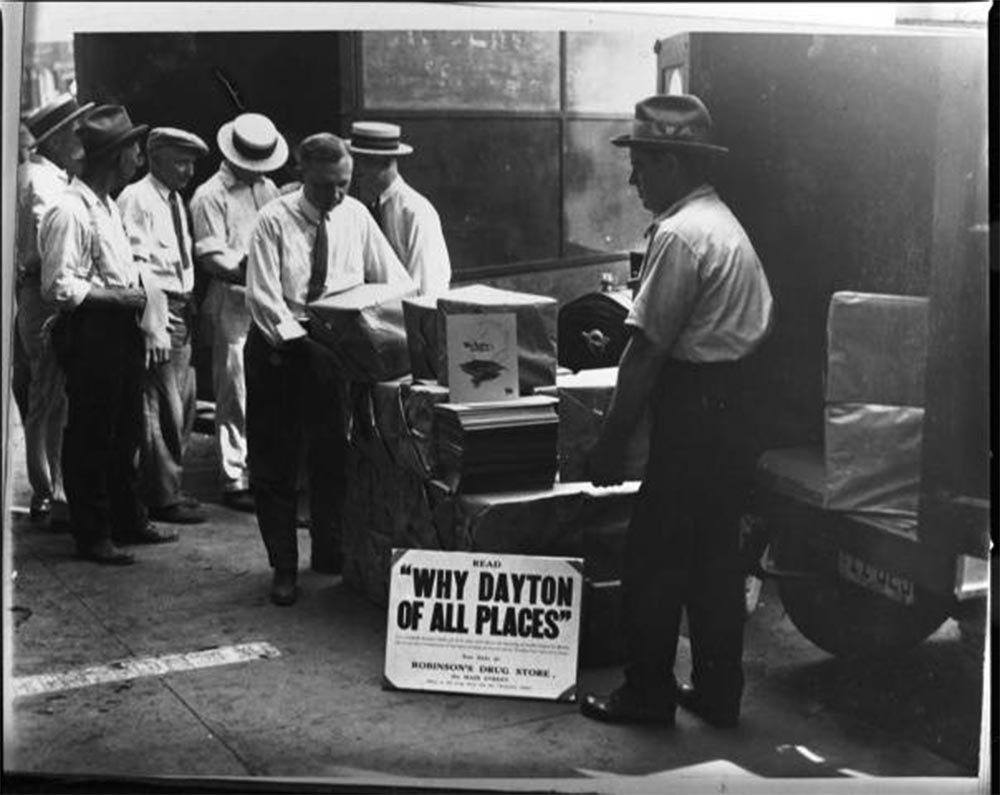

Tennessee gained further national attention during the so-called “Monkey Trial” of John T. Scopes. In 1925, the Legislature passed a law that forbade the teaching of evolution in public schools. Some local boosters in Dayton concocted a scheme to have Scopes, a high school biology teacher, violate the law and stand trial as a way of drawing publicity and visitors to the town. Their plan worked all too well, as the Rhea County courthouse was turned into a circus of national and even international media coverage. Thousands flocked to Dayton to witness prosecutor William Jennings Bryan and defense attorney Clarence Darrow argue their case.

Tennessee was ridiculed in the Northern press as the “Monkey State,” even as a wave of revivals defending religion swept the state. The legal outcome of the trial was unimportant. Scopes was convicted and fined $100, a penalty later canceled by the state court of appeals. The law itself remained on the books until 1967. The case was more important because it expressed the anxiety felt by Tennessee’s rural people over the threat to their traditional religious culture posed by modern science.

Another clash between community practices and the forces of the modern world took place in 1908 at Reelfoot Lake in the northwest corner of the state. The lake had for many years supported local fishermen and hunters who supplied West Tennessee hotels and restaurants with fish, turtles, swans, and ducks. Outside businessmen and their lawyers began buying up the lake and shoreline in order to develop it as a private resort. In the process, they denied access to the lake to local citizens who depended on the lake to earn a living. The residents tried to stop the developers in court. When that approach failed, they resorted to the old custom of vigilante acts, often called night-riding, to stop them.

Dressed in masks and cloaked in darkness, the night riders terrorized county officials, kidnapped two land company lawyers, and lynched one of them in the autumn of 1908. Governor Patterson called out the state militia to stop the violence; eight night riders were brought to trial, but all eventually went free. Fearing further outbreaks of violence over the private development of the lake, the state began to acquire the lake property as a public resource. In 1925, Reelfoot Lake was established as a state game and fish preserve, marking a first step toward the conservation of Tennessee’s natural resources.

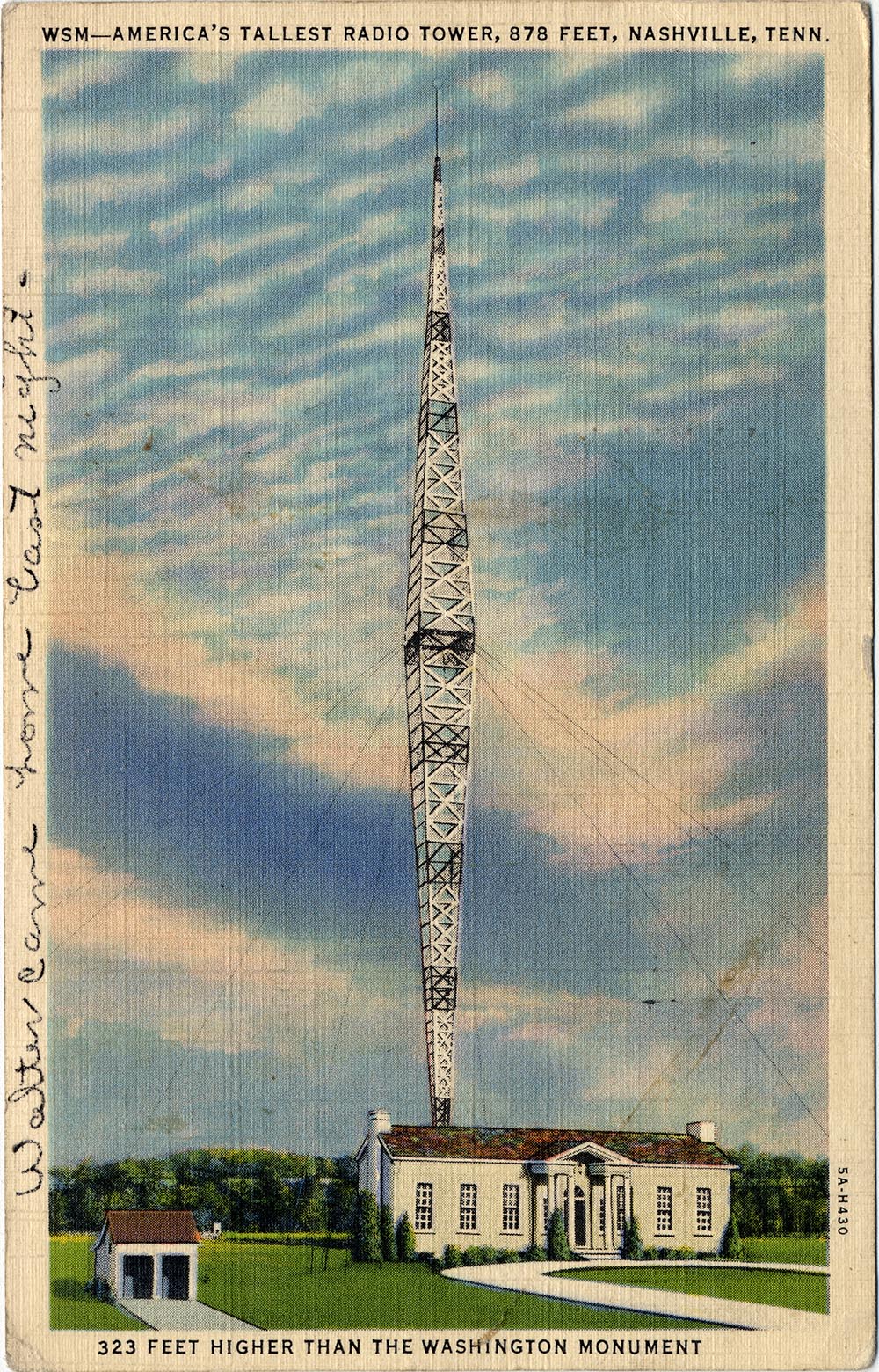

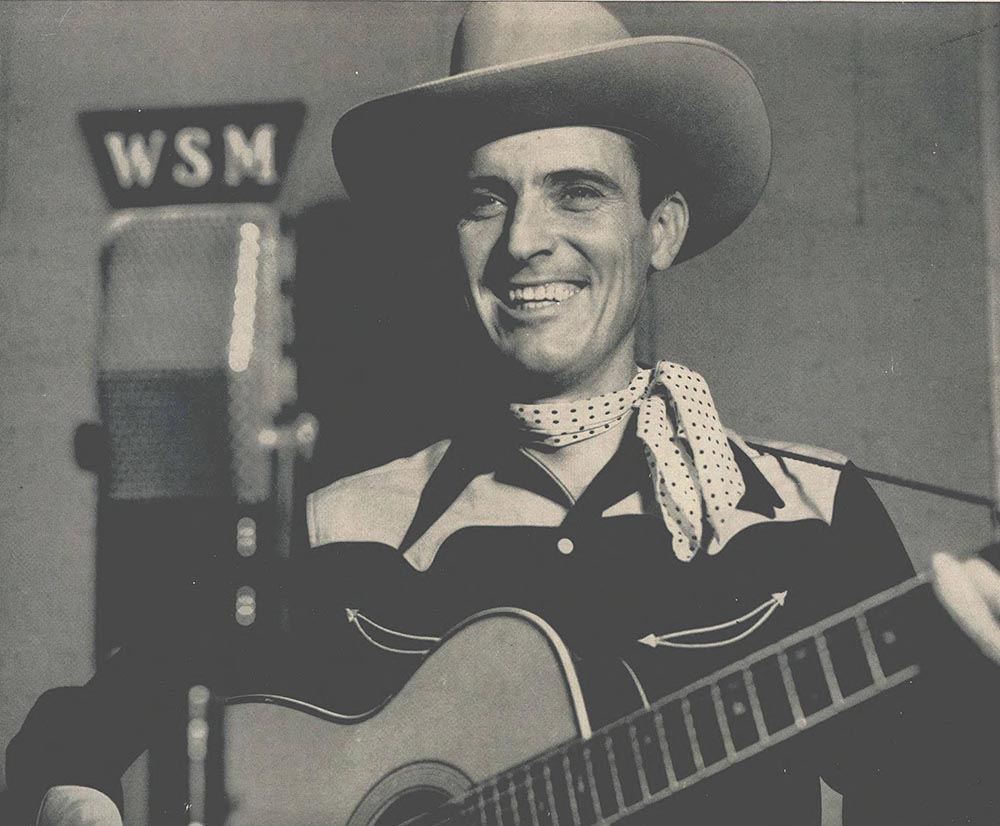

Ironically, at the very time that Tennessee’s rural culture seemed to be under attack, its music found a national audience. In 1925, WSM, a powerful Nashville radio station that could be heard throughout the South, began broadcasting a weekly program of live music that was soon known as the Grand Ole Opry. The Opry provided a wide range of entertainment including banjo-and-fiddle string bands of Appalachia, family gospel-singing groups, and country vaudeville acts like that of Murfreesboro native Uncle Dave Macon. Vaudeville acts combined singing, dancing, and comedy routines. One of the most popular stars of the Tennessee Opry was an African American performer, Deford Bailey. Still the longest-running radio program in American history, the Opry used the new technology of radio to tap into a huge market for “old-time” or “hillbilly” music. Two years after the Opry’s opening, field scouts of the Victor Company traveled to Bristol, Tennessee. There they recorded Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family to produce the first nationally popular rural records. Tennessee became known as the birthplace of traditional country music.

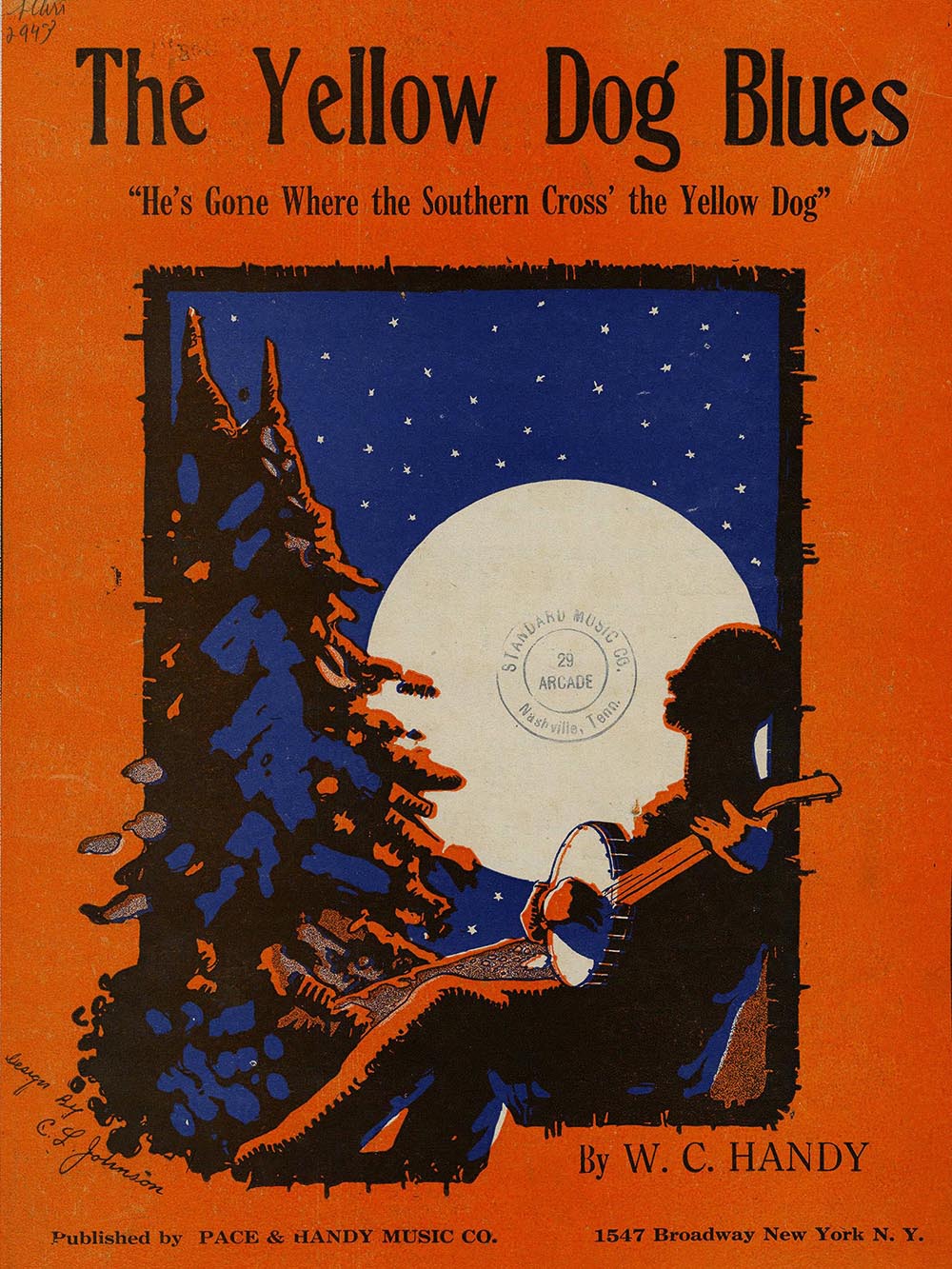

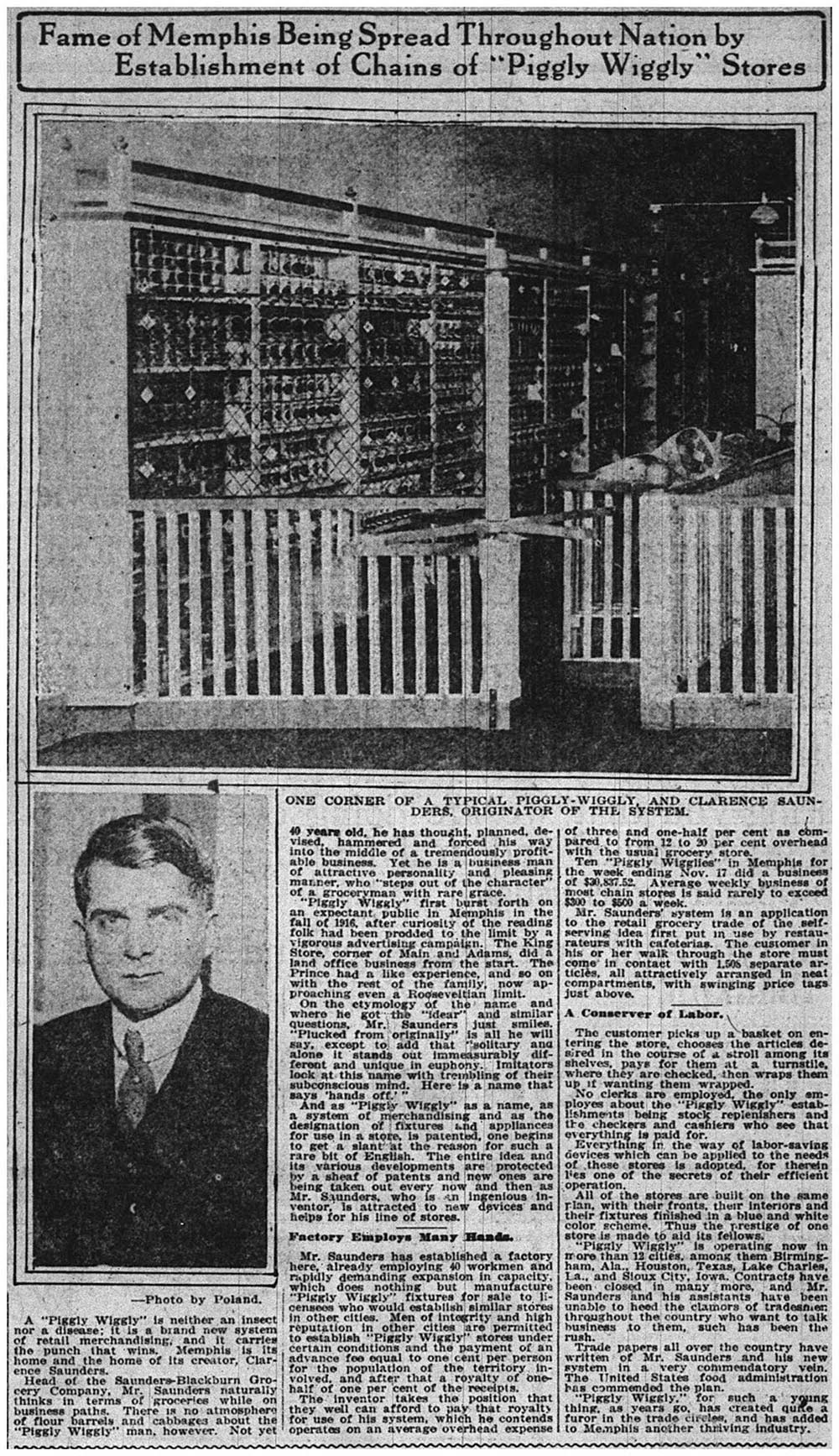

Just as Tennessee was fertile ground for the music enjoyed by white audiences, so was it a center for the blues music popular with African Americans. Both had their roots in the dances, harvest festivals, work songs, and camp meetings of rural communities. Because of its location at the top of the Mississippi River Delta, Memphis was a center for this music by the 1920s. The city became a magnet that drew performers from cotton farms to the clubs of Beale Street, the Upper South’s premier African American main street. Musician and composer W. C. Handy was able to transform blues songs into sheet music. This allowed blues music to spread outside the South. However, blues music lacked the radio exposure that benefited country music. Beale Street offered a rich musical setting where one could hear everything from W. C. Handy’s dance band to the jazz-accompanied blues of Ma Rainey or Chattanooga-born Bessie Smith. Delta blues spread across the country as better highways and the lure of wartime jobs brought greater numbers of rural African Americans into the cities. Memphis was also home to an important innovation in food purchasing. In 1916, Clarence Saunders opened Piggly Wiggly, the nation’s first self-service grocery store.

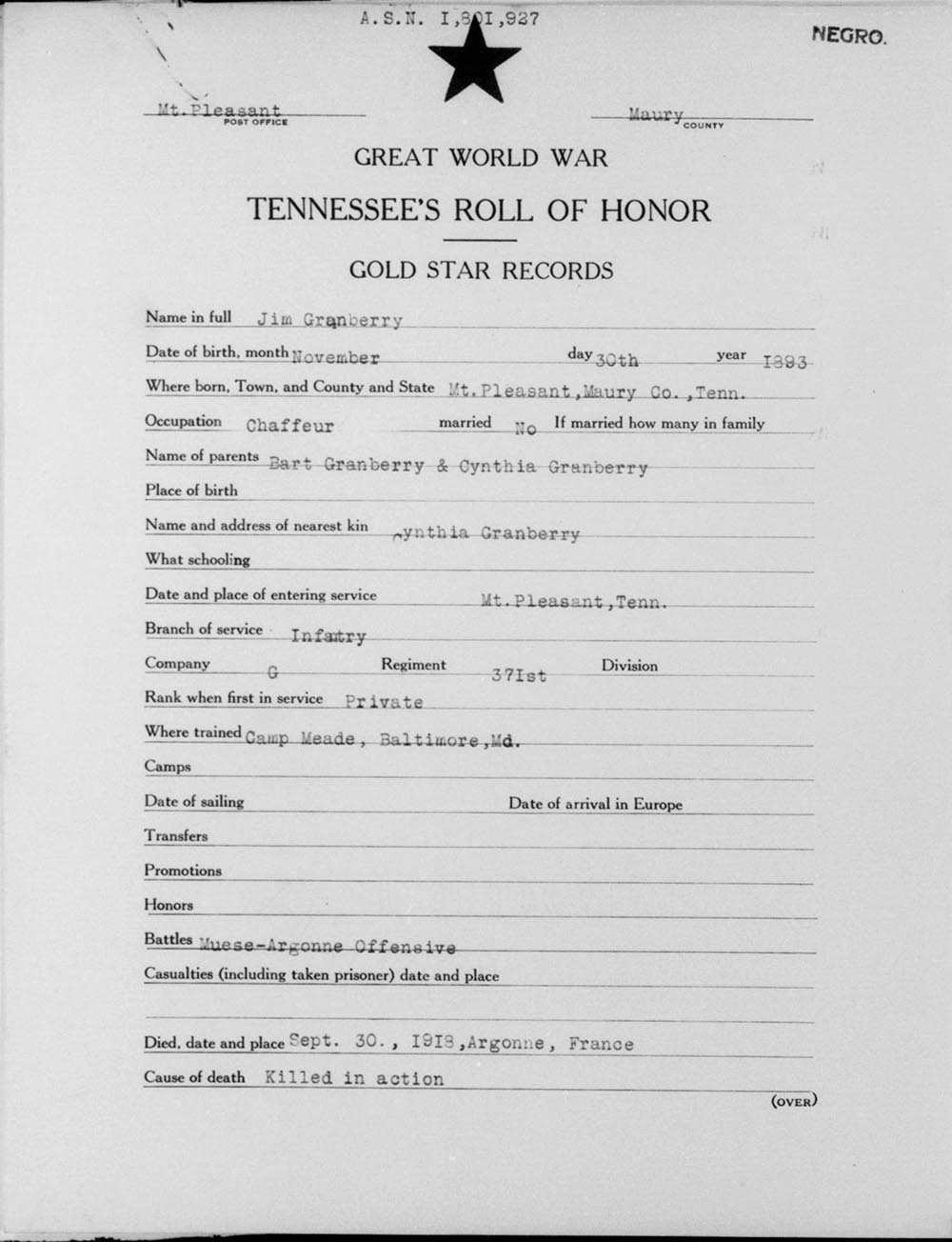

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, around 100,000 of the state’s young men volunteered or were drafted into the armed services. A large proportion of those men actually served with the American Expeditionary Force in Europe. More than 17,000 of the 61,000 Tennessee draftees were African Americans, although African American units were still segregated and commanded by white officers. Four thousand Tennesseans were killed in combat or died in the influenza epidemic that swept through the crowded troop camps in 1918. Lawrence Tyson of Knoxville played a key role in breaking the Hindenburg Line in September of 1918. The Hindenburg Line was a heavily fortified area near the border between France and Belgium considered to be Germany’s last line of defense. Tennessee provided the most celebrated American soldier of the First World War: Alvin C. York of Fentress County. York initially resisted serving in the military for religious reasons but later changed his mind. In October of 1918, York captured an entire German machine gun regiment in the Argonne Forest. As a result, York received the Congressional Medal of Honor as well as French military honors. York also became a powerful symbol of patriotism in the press and Hollywood film.

State politics and government were transformed following World War I. Austin Peay of Clarksville served as the first three-term governor since William Carroll, due in large part to the backing of rural and small-town voters. Governor Peay streamlined government agencies and reduced the state property tax while imposing an excise tax on corporate profits. An excise tax is a tax on a particular good or item. When his administration began, the state had only 250 miles of paved roads, but Peay undertook a massive roadbuilding program with the money generated by Tennessee’s first gasoline tax. He crisscrossed the state with thousands of miles of hard-surface highways, making him very popular among voters in rural areas.

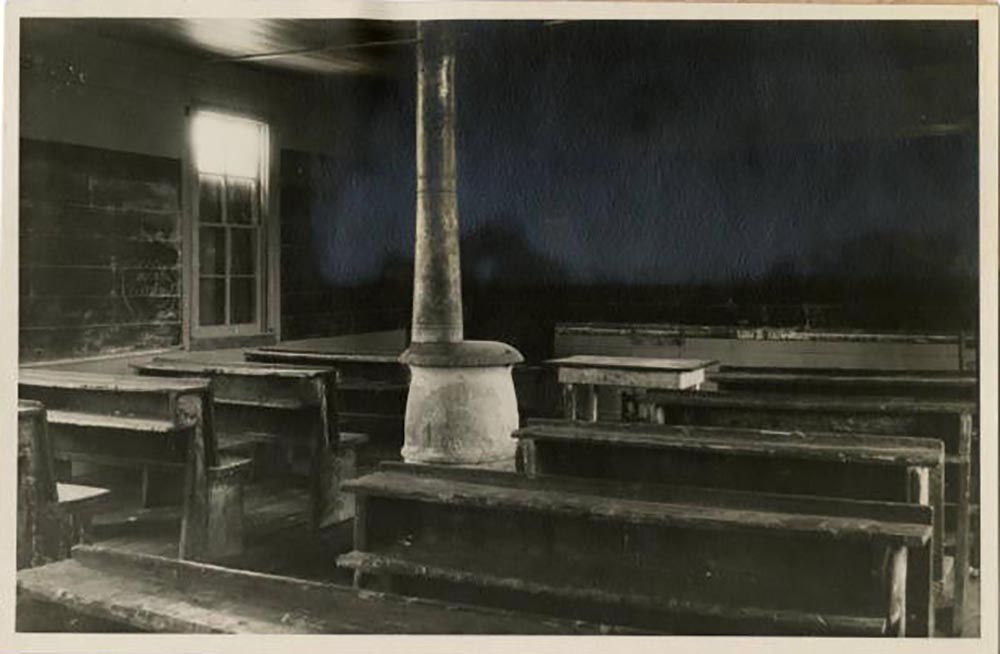

Another achievement of the Peay administration was the part it played in overhauling public education. At the beginning of the century, Tennessee had no state-supported high schools, and fewer than half its eligible children attended school. Teachers’ salaries were terrible, and the only public university did not receive any state funding. In 1909, the Legislature set aside twenty-five percent of the state’s revenue, or income, for education, and in 1913, that share was increased to one-third. A law requiring school attendance was passed, county high schools were established, normal schools for training teachers were built, and the University of Tennessee finally received state support. However, schools remained segregated so the Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial Normal School was built to serve African Americans. Building on this base, Governor Peay’s 1925 education law gave funding for an eight-month school term and began the modern system of school administration. The 1925 act also supplemented teacher salaries, standardized teacher certification, and turned the normal schools into four-year teacher colleges. Although some of these reforms did not survive the thirties, Tennessee nevertheless had dramatically improved its public school system.

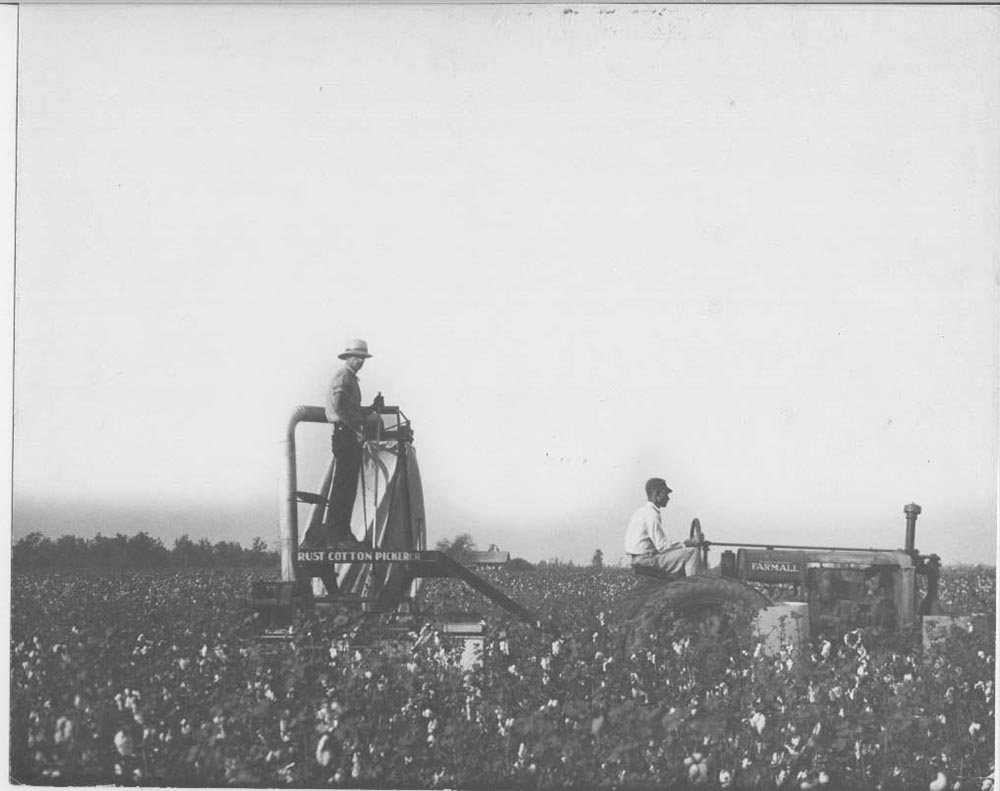

The stock market crash of October 1929 is usually considered to be the start of the Great Depression. In Tennessee, the hard times had started earlier, particularly for farmers. World War I had raised agricultural prices, but with the coming of peace, the export markets dried up and prices dropped. The longest and most devastating drought on record added to farmers’ problems. These problems drove many of the poorest farmers off the land as the old sharecropping system collapsed. Tractors and mechanical cotton pickers were also reducing the number of hands needed to farm. As a result, both white and African American sharecroppers migrated to cities in the 1920s. During this period known as the Great Migration, Tennessee’s African American population declined as thousands of people moved to northern industrial centers like Chicago.

Some of these country people found jobs at Tennessee factories, such as the DuPont plant in Old Hickory, rayon plants in Elizabethton, Eastman Kodak in Kingsport, and the Aluminum Company of America Works plant in Blount County. These large enterprises had replaced the earlier “rough” manufacturing—textiles, timber, and flour and mill products—as the state’s leading industries. The Alcoa plant was built specifically to take advantage of East Tennessee’s fast-falling rivers in order to generate electricity. Private hydroelectric dams were constructed in the state as early as 1910, and the possibility of harnessing rivers to produce power would eventually prove a strong attraction for industry. Tennessee was still a predominantly agricultural state, but it now had a growing industrial workforce. In East Tennessee, it also had the beginnings of an organized labor movement. Strikes, while less common than in northern states, were becoming more widespread. However, Tennessee’s industrial economy was soon damaged by the shutdowns and high unemployment of the 1930s.

The Depression made everyone’s life worse: farmers produced more and made less in return; young people left the farms only to be laid off from jobs in the cities; merchants could not sell their goods; doctors had patients who could not pay; and teachers were paid in heavily discounted scrip instead of U.S. currency. Scrip is a type of paper currency issued by a private company or local government. In the countryside, people dug ginseng or sold walnuts to make a little extra income. City dwellers lined up for “relief” in the form of food or went back to the farms where they could at least survive. Local governments were unable to collect taxes, and hundreds of businesses failed (578 in 1932 alone). In 1930, the failure of three major banking institutions, including Caldwell and Company, brought most financial business in the state to a grinding halt. The collapse of the financial empire of Nashvillian Rogers Caldwell cost the state $7 million, and thousands of depositors lost their savings. The collapse nearly caused the impeachment of newly elected Governor Henry Horton. Governor Horton had close ties with Caldwell and his political ally, Luke Lea, a newspaper publisher who was ultimately convicted of fraud and sent to prison.

Former Memphis Mayor Edward H. Crump led the outcry against Horton and quickly assumed the role as “boss” of state politics and Shelby County. Between 1932 and 1948, anyone who wished to be governor or senator had to have Crump’s blessing, although some of his followers defied the “boss” once they were in office. A two-dollar poll tax kept voter turnout low during these years. However, the Crump organization routinely paid the tax for Shelby County voters who voted as they were told. This meant Shelby County often produced the majority of the state’s votes and allowed Crump to control statewide Democratic primaries. In 1936, for example, Gordon Browning won election as governor with the help of 60,218 votes from Shelby County to only 861 for his opponent. Crump was the most powerful politician in Tennessee during most of the thirties and forties, by virtue of being able to deliver a vast bloc of votes to whichever candidate he chose.

Mayor Crump and Nashville Mayor Hilary Howse’s political machines succeeded in part because of the support they received from black political organizations. Robert Church, Jr., was the political leader of the Memphis black community, a major Republican power broker, and a dispenser of hundreds of Federal jobs. In Nashville, James C. Napier held much the same position as a political spokesman for middle-class African Americans. These leaders followed a moderate course, avoiding confrontation and accepting the limited rights and freedoms offered by white politicians like Crump. However, other African Americans were willing to attack “Jim Crow” laws more directly. In 1905, R. H. Boyd and other Nashville businessmen followed a successful boycott of segregated streetcars by organizing a competing, black-owned streetcar company. Twenty years later in Chattanooga, black workingmen organized to defeat a revived Ku Klux Klan at the polls. They also formed a local chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association following a visit from Black Nationalist leader Marcus Garvey. By taking industrial jobs at higher wages, serving in the military, or simply leaving the landlord’s farm, African Americans achieved a degree of independence that made them less willing to tolerate second-class citizenship.

For the first time since Reconstruction, Tennesseans returned to the national political spotlight in the 1920s. Joseph W. Byrns of Robertson County was Speaker of the United States House of Representatives during the crucial early years of the New Deal. Senator Kenneth D. McKellar of Memphis, who worked closely with the Crump organization, served six consecutive terms, from 1916 to 1952. As powerful chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, he steered a considerable amount of military spending and industry Tennessee’s way during World War II. Cordell Hull of Celina served in Congress from 1907 to 1933, except for the two years he spent as Democratic National Chairman. Hull authored the 1913 Federal Income Tax bill and guided American foreign policy for twelve years as Secretary of State.

Tennesseans, like most Americans, gave a tremendous majority to Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1932 presidential election. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs would have as great an impact in Tennessee as anywhere in the nation. One hundred thousand farmers statewide participated in the crop reduction program of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), while 55,250 young men enlisted in one of the thirty-five Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in the state. The road building projects and public works of the Public Works Administration (PWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) put thousands of unemployed Tennesseans to work. New Deal agencies spent large sums of tax dollars in Tennessee ($350 million in 1933–1935 alone) in an effort to stimulate the region’s economy through public employment and investment. The Cumberland Homesteads project gave farmland and homes to poor families. Families could use the farm products to meet their basic needs or provide supplemental income. The community in Cumberland County eventually had 251 homes with electricity and indoor plumbing as well as two schools and a variety of other community buildings.

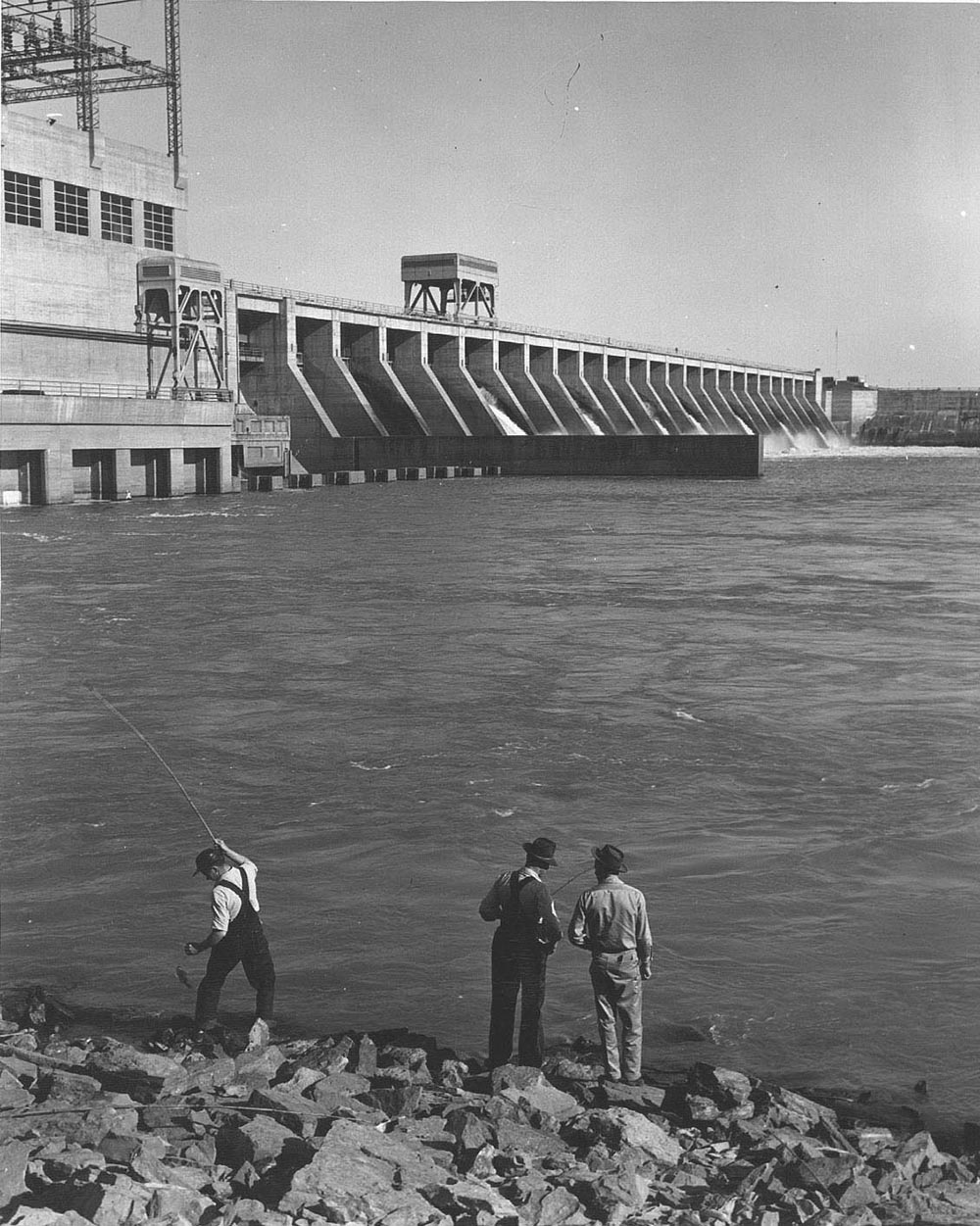

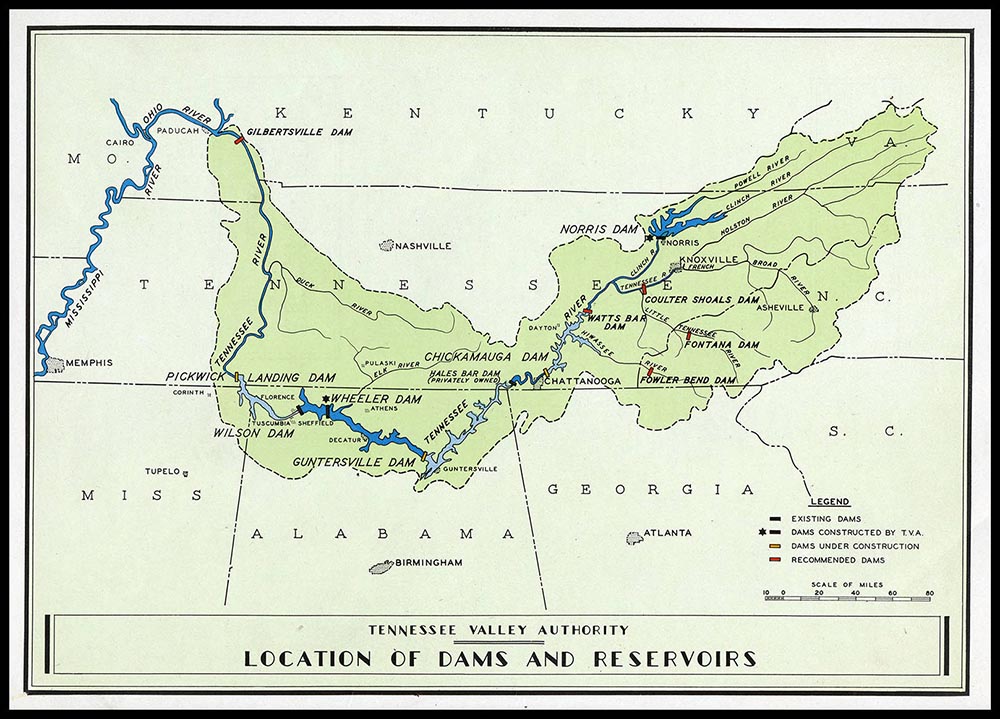

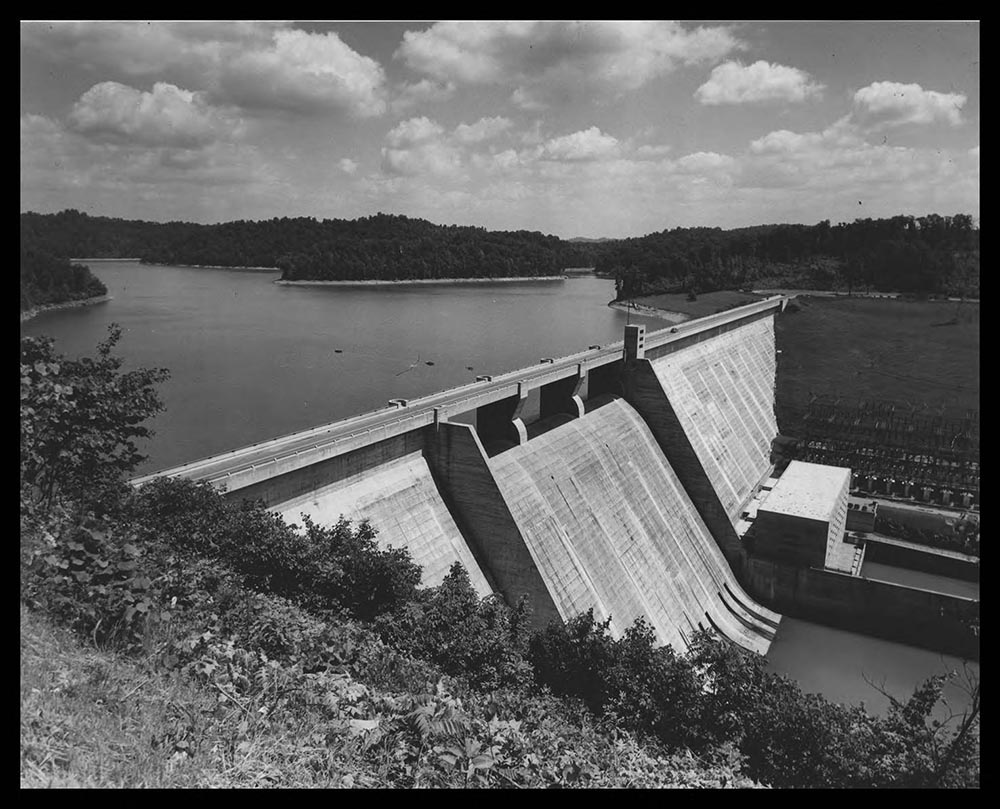

By far the greatest expenditure of Federal dollars in Tennessee was made through the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). In one way or another, TVA had an impact on the lives of nearly all Tennesseans. The agency was created in 1933, due to the persistence of U.S. Senator George Norris of Nebraska. TVA’s headquarters were located in Knoxville. TVA was charged with the task of planning the total development of the Tennessee River Valley. TVA sought to do this primarily by building twenty hydroelectric dams between 1933 and 1951. Hydroelectric dams convert the energy generated by falling water into electricity. TVA also built several coal-fired power plants to produce electricity. TVA’s first project was a dam on the Clinch River. Some local residents thought the dam would benefit the area by bringing construction jobs and manufacturing jobs in the future. Other residents opposed the project because it would flood thousands of acres of farmland and force families off land they had owned for generations. TVA worked with residents to address some concerns. For example, TVA relocated family and community cemeteries from land that would be flooded. Some residents attempted to stop the dam through the courts, while others simply stayed on their land until removed. Ultimately, Norris Dam was completed in March 1936. The main benefit of TVA was that it brought inexpensive and abundant electrical power to Tennessee, particularly to rural areas that previously did not have electrical service. TVA electrified some 60,000 farm households across the state. By 1945, TVA was the largest electrical utility in the nation, a supplier of vast amounts of power whose presence in Tennessee attracted large industries to relocate near one of its dams or steam plants.

One group of Tennessee-based intellectuals achieved national fame by questioning the desirability of such industrialization for the South. The “Agrarians” at Vanderbilt University celebrated the region’s agricultural history and challenged the wisdom of moving rural people aside to make room for modern development. Donald Davidson, in particular, objected to massive government land acquisitions that displaced communities and flooded some of the best farmland in the Valley. TVA, for example, purchased or condemned 1.1 million acres of land, flooded 300,000 acres, and moved the homes of 14,000 families in order to build its first sixteen dams. On a slightly smaller scale, 420,000 acres of forested, mountainous land along the crest of the Appalachian range was set aside during the 1930s for a national park. Although much of this land belonged to timber companies, creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park displaced some 4,000 mountain people, including long-standing communities like Cades Cove. The price of progress was often highest for those citizens most directly affected by such projects.

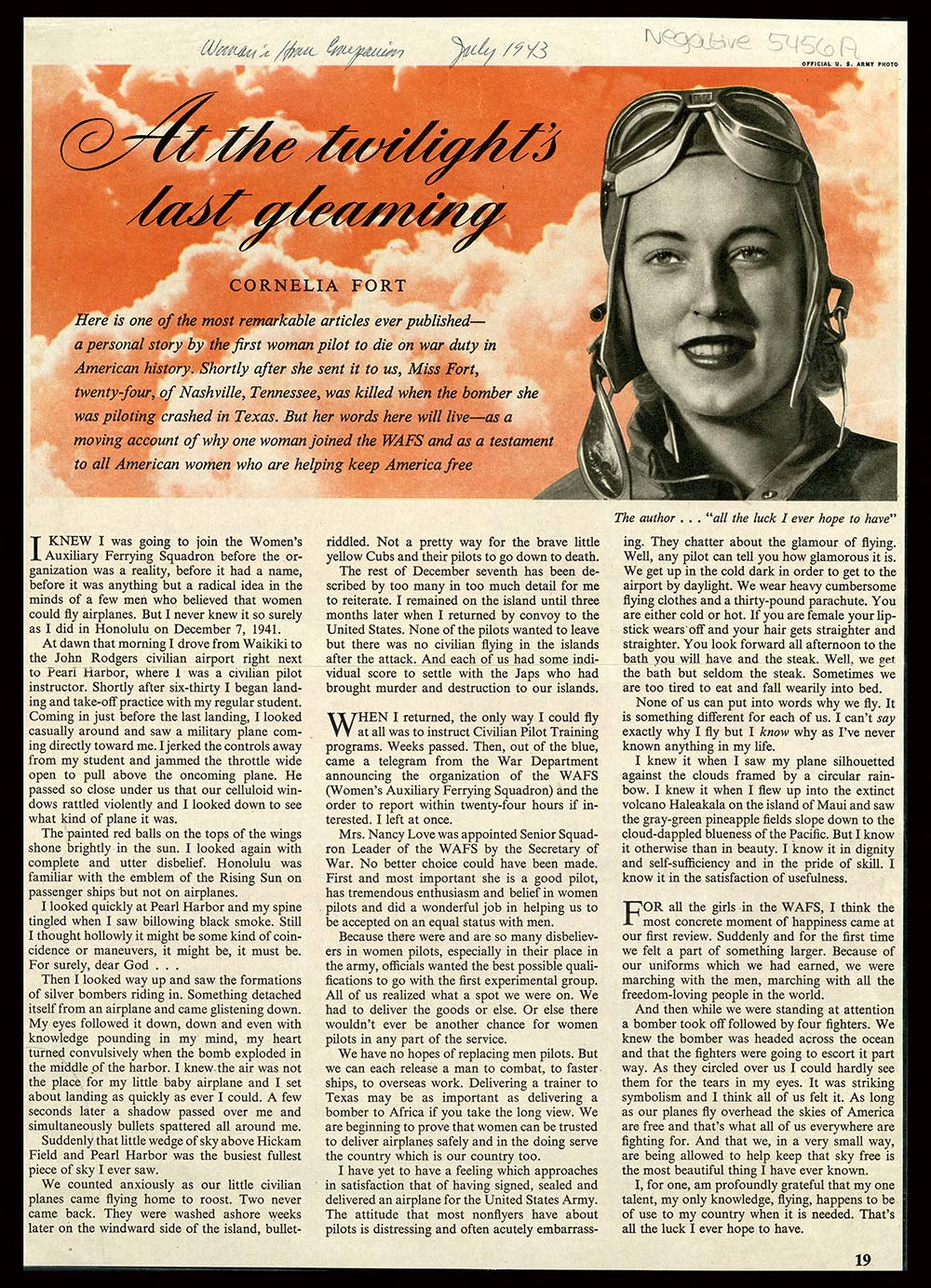

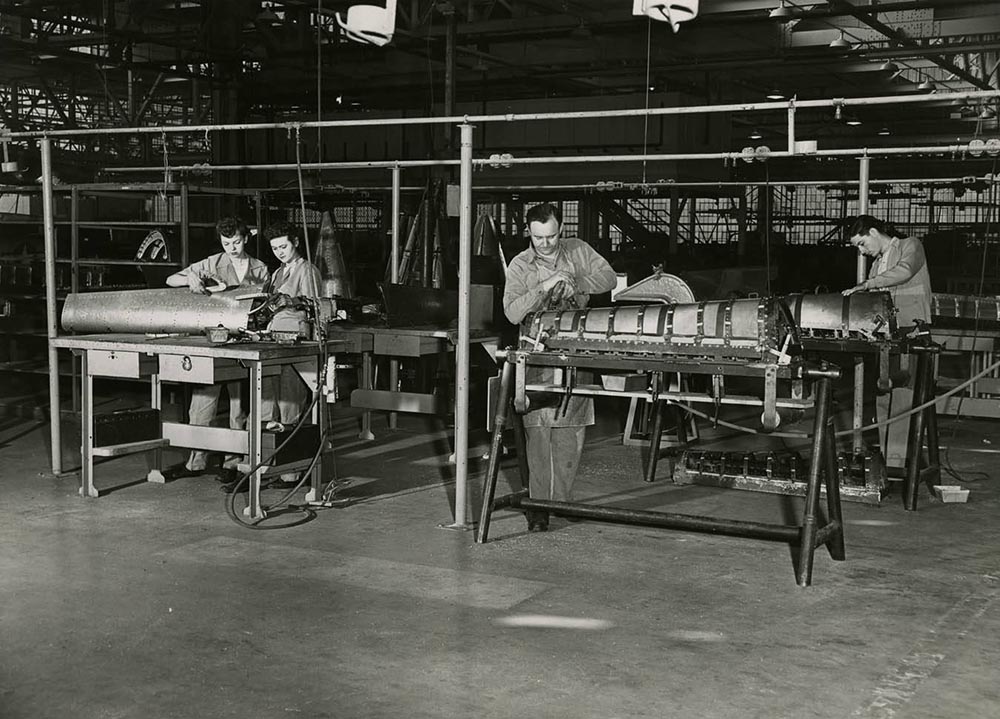

Despite the millions of dollars that TVA and the Federal government pumped into Tennessee, the Depression ended because of the economic boost that came from going to war. World War II brought relief mainly by employing ten percent of the state’s populace (308,199 men and women) in the armed services. Most of those who remained on farms and in cities worked in war-related production, as Tennessee received war orders amounting to $1.25 billion. From the giant shell-loading plant in Milan to the Vultee Aircraft works in Nashville and the TVA projects in East Tennessee, war-based industries hummed with the labor of a greatly enlarged workforce. Approximately thirty-three percent of the state’s workers were female by the end of the war. Nashvillian Cornelia Fort witnessed the attack on Pearl Harbor and went on to serve as a pilot in the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, or WAFS. Fort was killed in a midair collision in 1943. Tennessee military personnel served with distinction from Pearl Harbor to the final, bloody assaults at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and 7,000 died in combat during the war. In 1942–1943, Middle Tennessee residents played host to twenty-eight army divisions that swarmed over the countryside on maneuvers preparing for the D-Day invasion. Camp Forrest in Tullahoma served as a prisoner of war camp for German and Italian POWs.

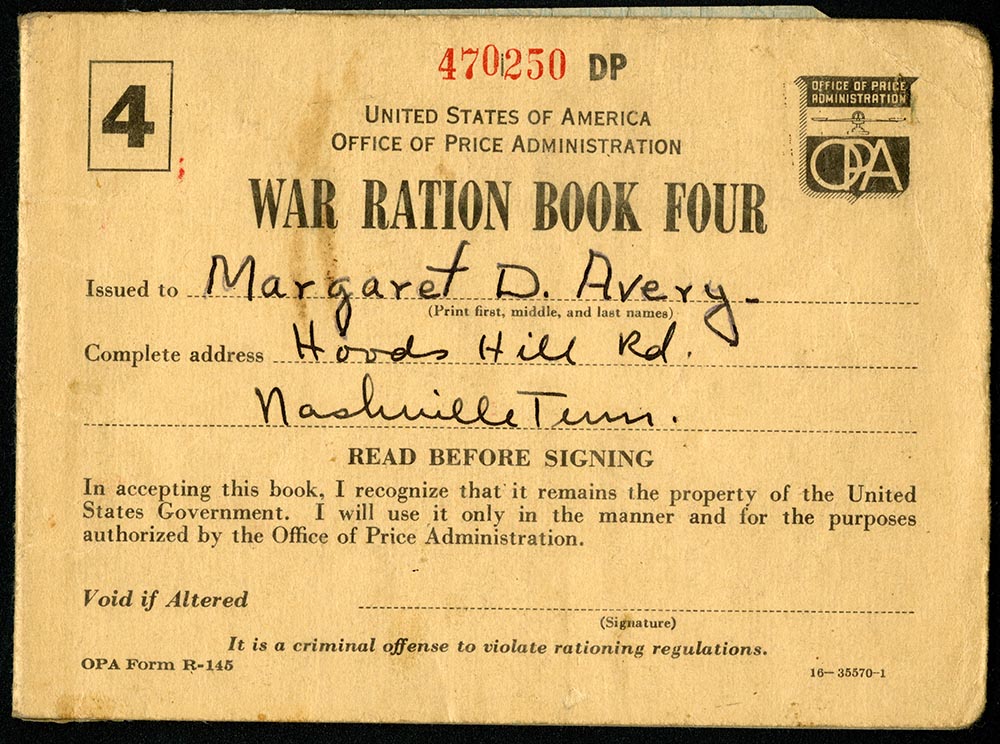

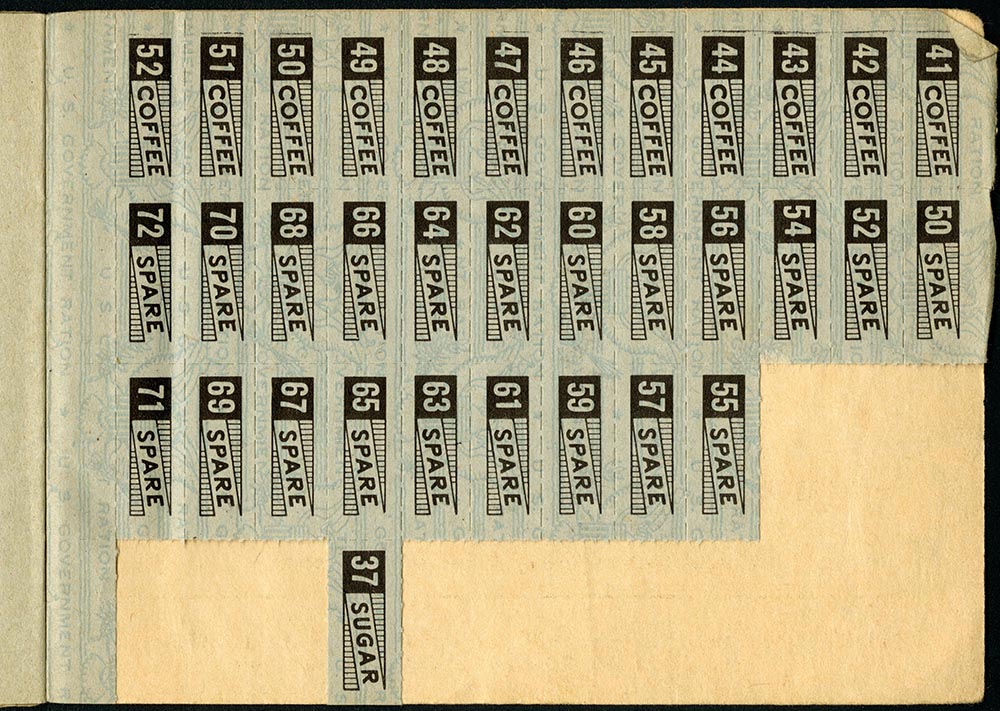

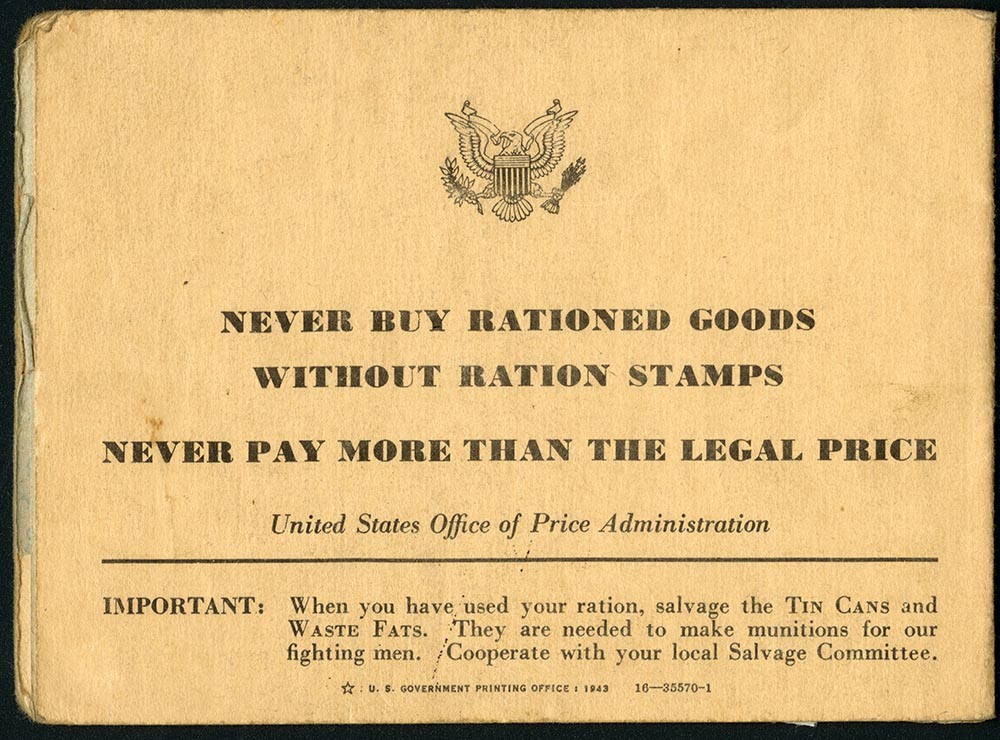

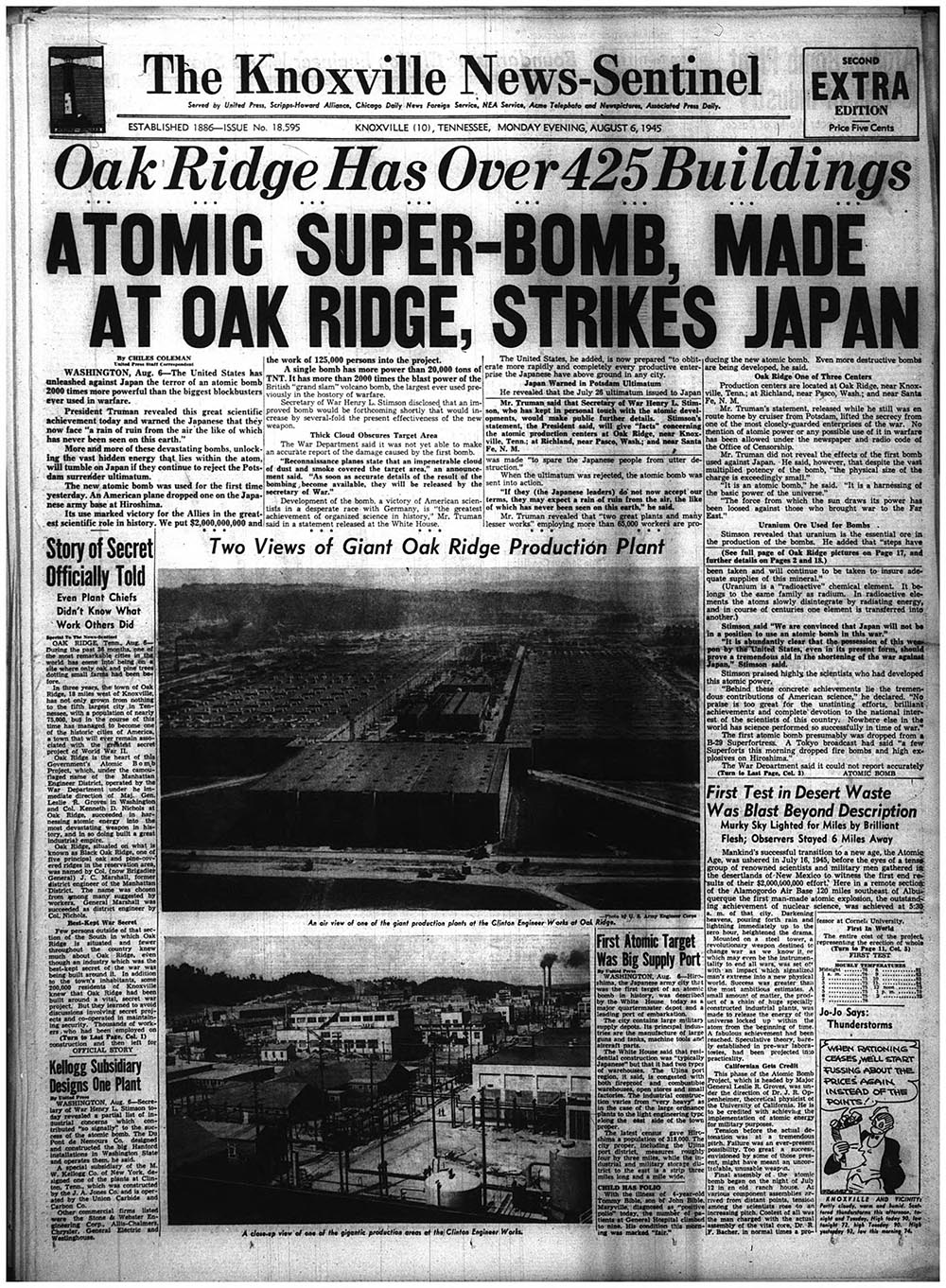

Tennesseans participated in all phases of the war—from combat to civilian administration and military research. Cordell Hull served twelve years as President Roosevelt’s Secretary of State and became one of the chief designers of the United Nations, for which he received the Nobel Peace Prize. Ordinary citizens experienced the war’s hardships through the rationing of food, gasoline, and other items. The government rationed, or limited the amount of goods civilians could purchase, to fulfill the needs of the military. The government encouraged families to plant victory gardens to produce vegetables. They were called victory gardens because they ensured that there was enough canned food available for American soldiers and sailors. Especially significant for the war effort was Tennessee’s role in the Manhattan Project, the military’s top secret project to build an atomic weapon. Research and production work for the first A-bombs were conducted at the huge scientific-industrial installation at Oak Ridge in Anderson County. The Oak Ridge community was entirely a creation of the war: it grew from empty woods in 1941 to Tennessee’s fifth-largest city, with a population of 70,000, four years later. Twice in 1945, city streets and courthouse squares erupted with celebrations as the news of victory in Europe and the Pacific reached the state. For Tennessee, World War II constituted a radical break with the past. TVA had transformed the physical landscape of the state, and wartime industrialism had irreversibly changed the economy. Soldiers who had been overseas and women who had worked in factories returned home with new expectations for the future.