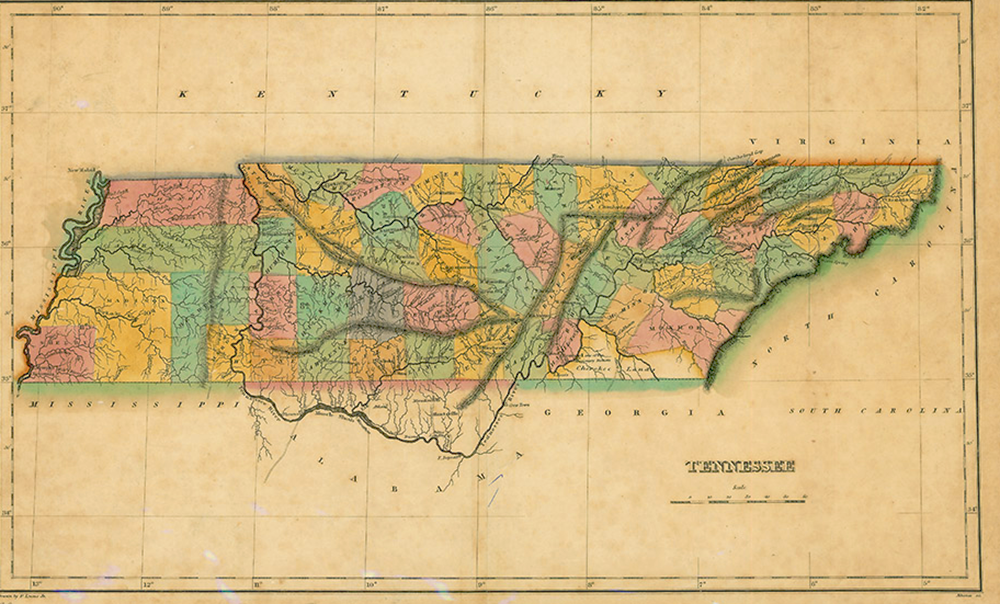

The frontier phase of Tennessee’s history ended with the rapid settlement of West Tennessee after the Jackson Purchase. However, that did not end Tennesseans’ urge to move west. Large numbers of Tennesseans settled in Arkansas, Texas, Missouri, Illinois, Mississippi, and Alabama and joined enthusiastically in the California gold rush.

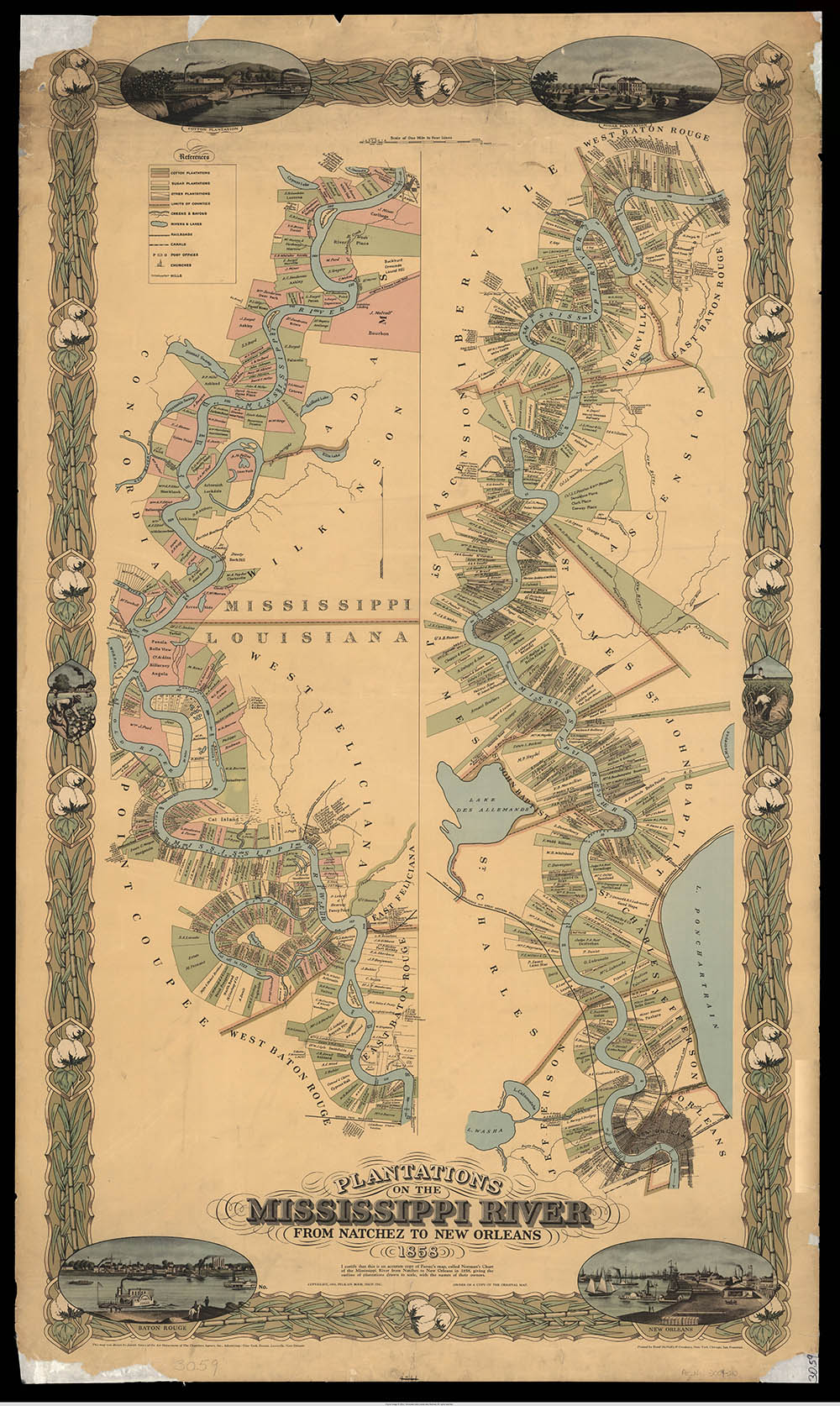

As Tennessee developed, the need for reliable transportation to connect the state to the rest of the nation increased. By 1820, the first steamboats reached Nashville. Steamboats made it faster, easier, and cheaper for farmers in Middle Tennessee to sell their products in downriver markets. Goods often arrived at Nashville by steamboat and were then transported overland on roads that radiated from the city like the spokes of a wheel. The most famous of these roads, the Natchez Trace, connected Middle Tennessee directly with the lower Mississippi River. Memphis was established in the southwestern corner of the state after the Jackson Purchase. The town quickly developed into a thriving river port because of its steamboat traffic. Cotton bales from plantations were carted into Memphis to be loaded onto boats and shipped to New Orleans.

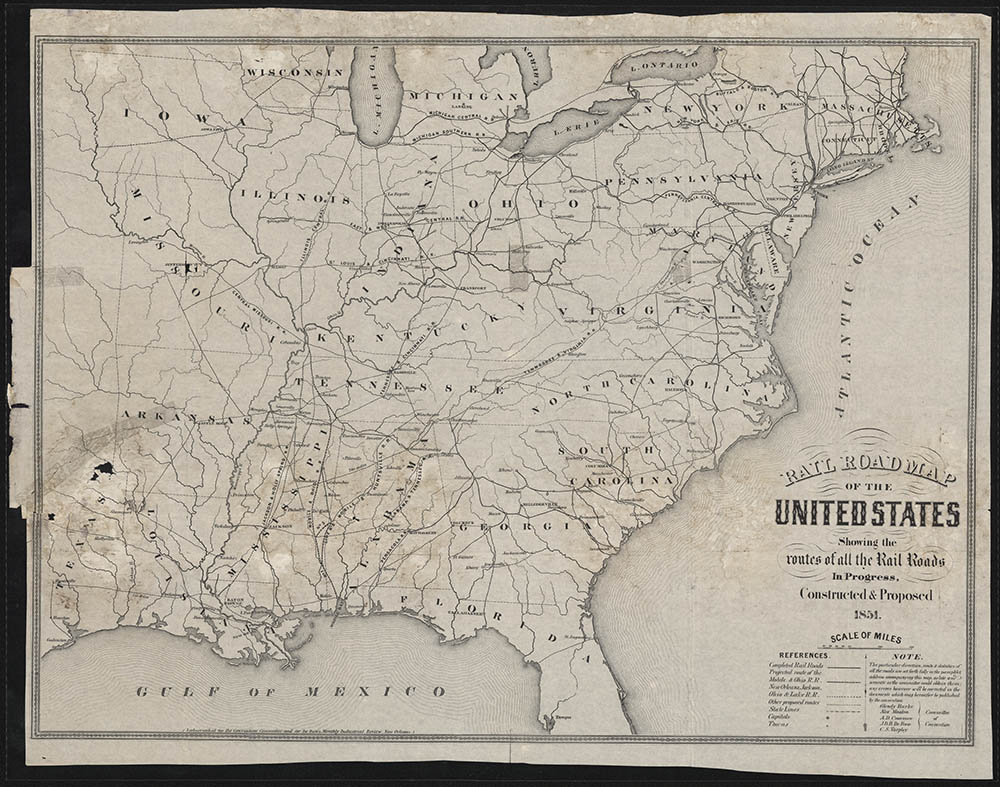

East Tennessee’s transportation problems were more difficult to solve because the region was landlocked. A landlocked region is one that has no access to larger bodies of water such as a sea. Though the Tennessee River ran through the region, it contained many shoals and other obstructions that made it very difficult to navigate. Shoals are shallow areas in rivers that often contain many sandbars. Although the steamboat Atlas managed travel as far as Knoxville in 1828, businessmen in East Tennessee began asking for state assistance in building railroads. However, government officials opposed such spending so Tennessee got a late start in railroad construction. The state had no railroad mileage in 1850, but by 1860, 1,200 miles of track had been laid, most of it in East Tennessee. East Tennessee’s railroads connected it to markets on the East Coast, but there was no line that connected Knoxville directly with Nashville. As East Tennessee began to develop railroads, coal mines, and industries, it became even more separate from the rest of the state.

Tennessee agriculture achieved great success during this period. In 1840, the state was the largest corn producer in the nation, and in 1850, it raised more hogs than any other state. Tennessee’s transportation network allowed it to export food downriver to supply plantations in the Deep South. Tennessee benefited from growing a variety of crops including fruits, vegetables, hemp, tobacco, and grains. Farmers also raised mules and other livestock. Many southern states devoted so much land to growing cotton that they had to import food. Tennessee served as a breadbasket, or grain supplier, to states further south. This connected Tennessee to the cotton economy, but also made Tennessee different.

During this time period, Tennessee’s cultural and intellectual life developed rapidly. Nashville became an early center of the arts and education in the South. Many traditional American tunes were preserved thanks to the music publishing industry which started in 1824. By the 1850s, the University of Nashville had grown into one of the nation’s leading medical schools. Many of the physicians west of the Appalachians received their training there.

The noted Philadelphia architect William Strickland came to Nashville in 1845 to design and build the new state capitol. The design of the capitol was based on the architecture of ancient Greece. Strickland, Nathan Vaught, and the Prussian-born architect Adolphus Heiman also designed a number of elaborate churches and homes in Middle Tennessee. Businessmen and wealthy planters employed silversmiths, engravers, furniture makers, stencil cutters, printers, and music teachers. Early Tennessee portrait painters, such as Ralph E. W. Earl, Washington B. Cooper, and Samuel Shaver, produced numerous portraits.

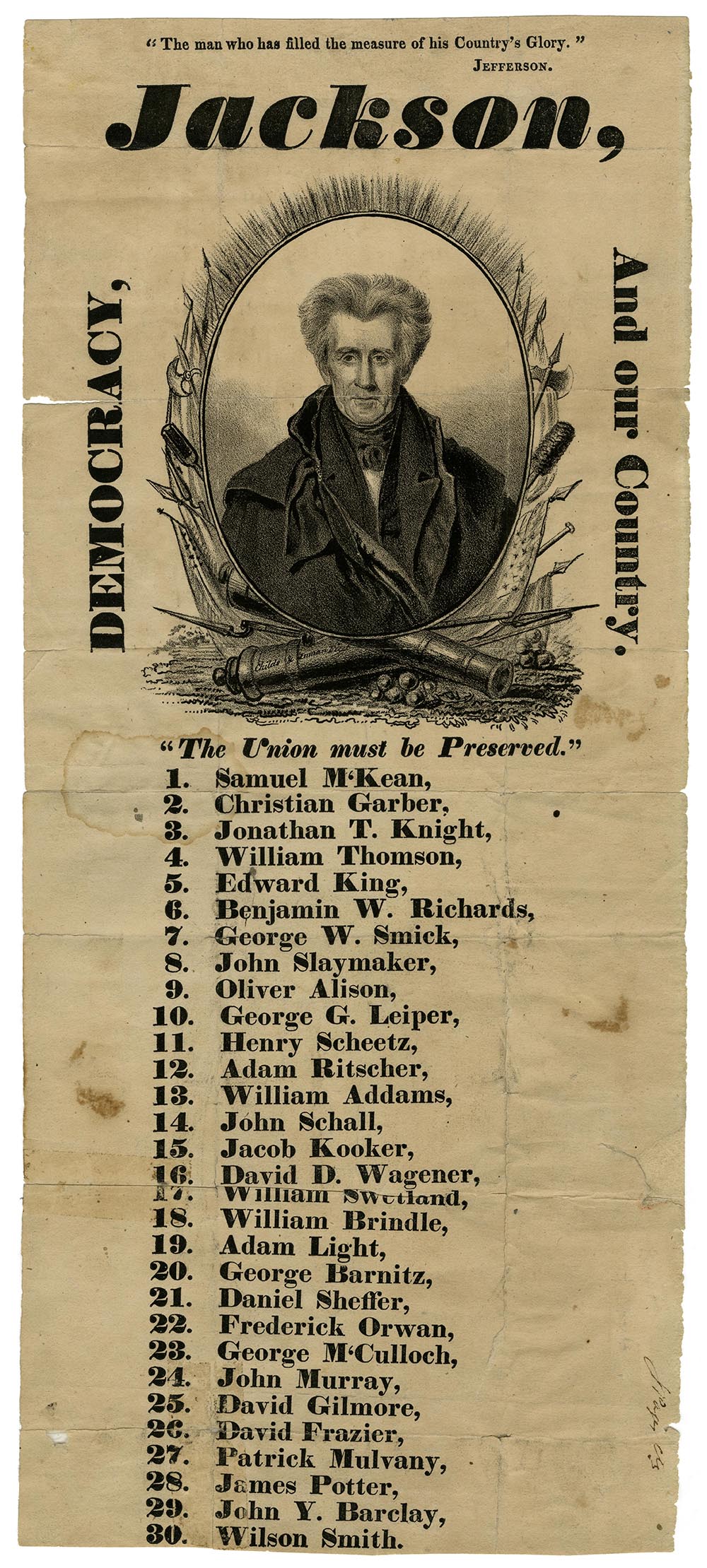

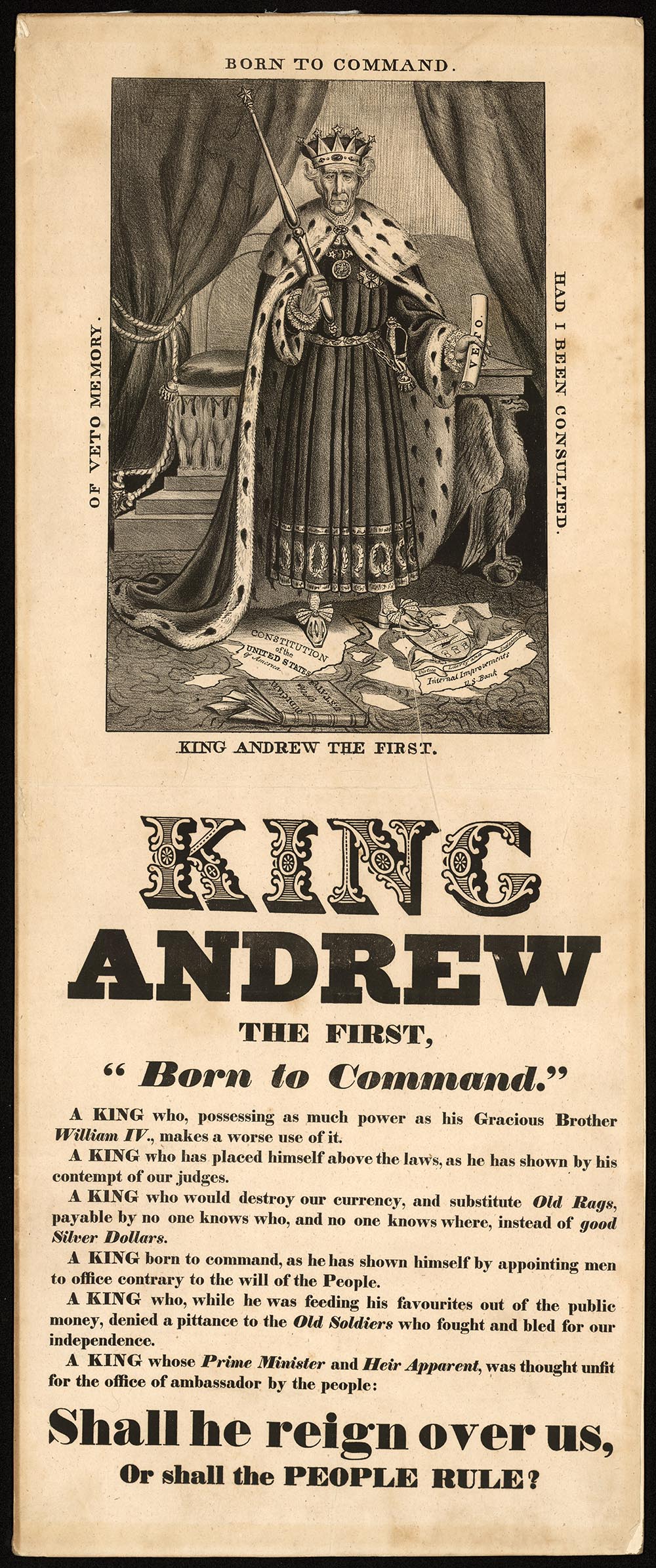

From 1820–1850, Tennessee politicians had a huge influence on the nation. None had more of an impact than Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s campaigns revolutionized, or radically changed, the American electoral system. Jackson lost the presidency in 1824 even though he received more popular votes, or votes from the people, than the other candidates. He also received more electoral votes than the other candidates, but not the majority he needed to be president. The House of Representatives had to decide between Jackson and John Quincy Adams, who had received the second-highest number of votes. Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, made a deal with Adams. Clay would influence the members of the House to vote for Adams, if Adams made Clay the Secretary of State. Adams agreed and became president. Jackson’s supporters referred to the deal as the “corrupt bargain.” Many voters viewed the “corrupt bargain” as unfair, which caused them to vote for Jackson in 1828 and 1832. Jackson won both elections by a landslide majority. A landslide majority is when one candidate wins by a huge number of votes. Huge numbers of new voters took part in the elections of 1828 and 1832 because of changes to voting requirements. Jackson’s election signaled a shift in political power away from Virginia and New England to the west. Even after Jackson’s second term as president ended, he continued to have enormous influence over Tennessee and national politics.

|

|

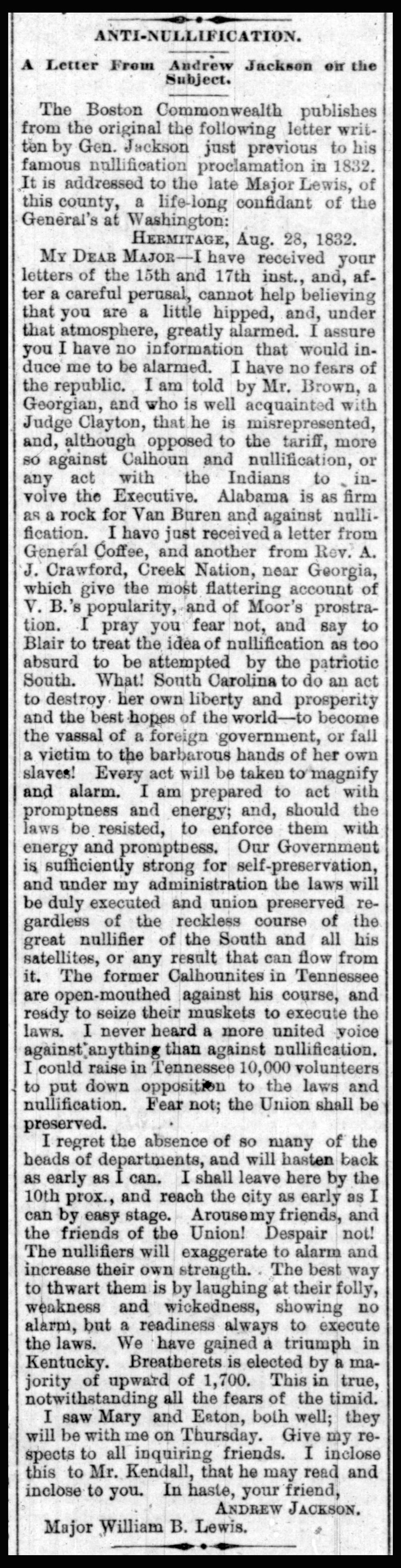

Jackson faced several crises during his eight-year presidency. He clashed with South Carolina politicians who voted to nullify, or ignore, a Federal tariff, or tax. Jackson refused to back down even when South Carolina threatened to secede, or leave, the Union. Jackson also attacked the Bank of the United States because he viewed it as favoring the wealthy while denying loans to ordinary people. Jackson eventually won when the bank’s charter expired in 1836.

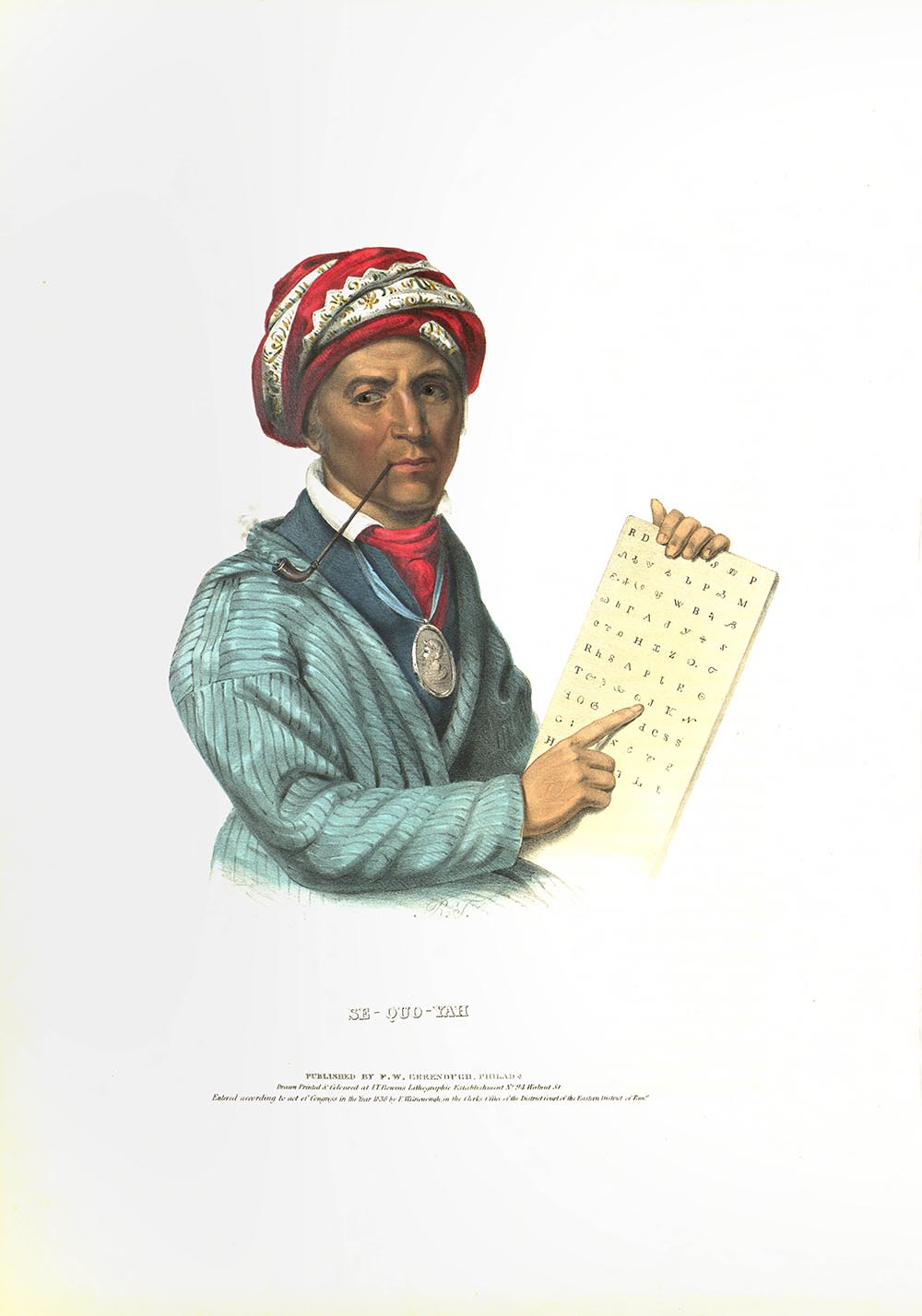

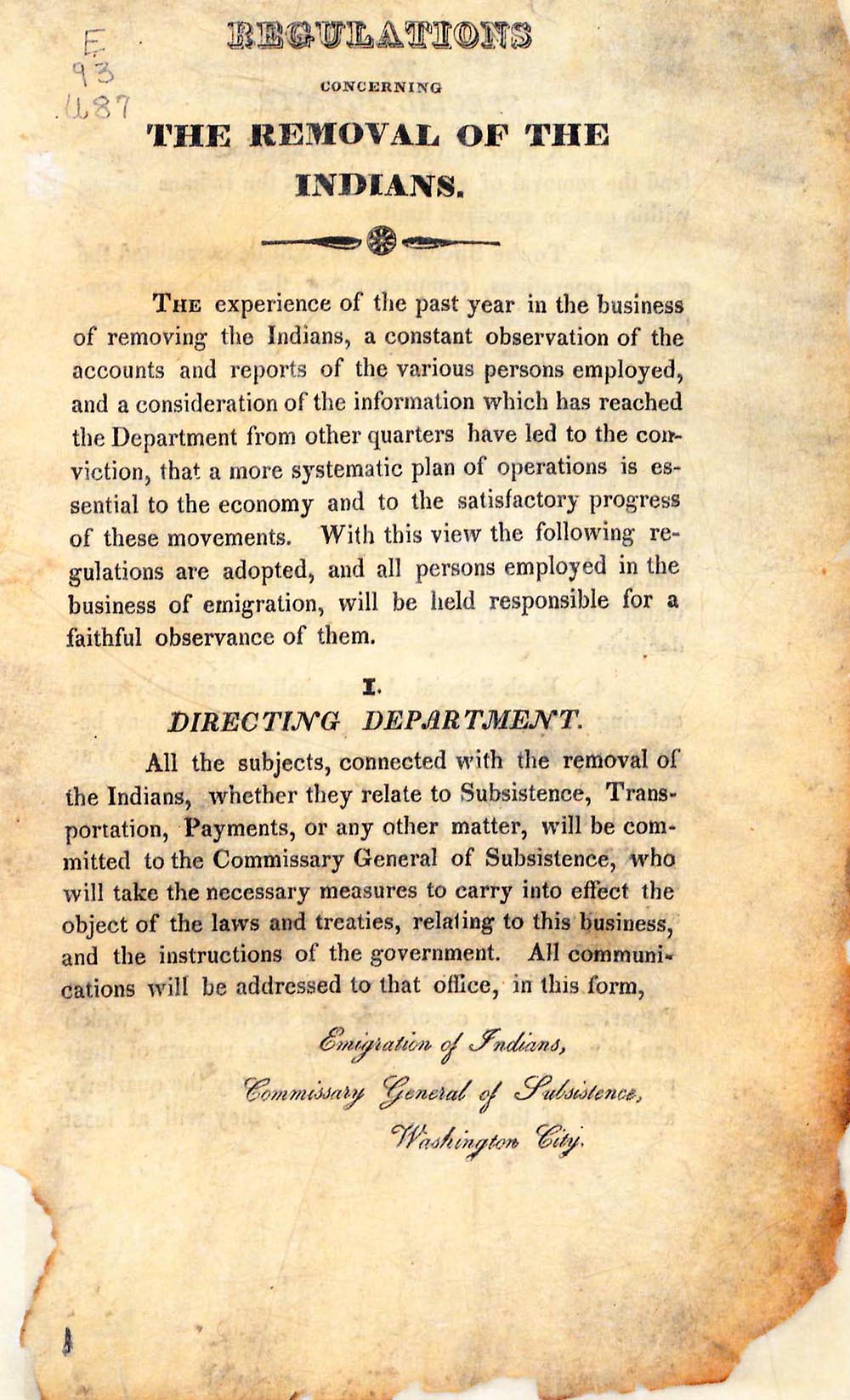

Most important for Tennessee was Jackson’s Indian removal policy. Jackson and his supporters in Congress wanted to move Native Americans to land west of the Mississippi River. Indian removal began when Georgia attempted to take over Cherokee land and property in that state. The Cherokee in North Georgia and Southeast Tennessee had adopted many elements of white culture including converting to Christianity, becoming slave owners, and writing a constitution. Sequoyah created a writing system for the Cherokee language that allowed the Cherokee to become more literate than their white neighbors. Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross decided to fight the removal policy in the court system. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee, but Jackson refused to enforce the decision. Georgia was allowed to continue with its plans to take Cherokee land, and Jackson ordered the army to forcibly remove the Cherokee from their lands if necessary. A small number of tribe members gave in to the increasing pressure from the government and signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. However, most Cherokee firmly opposed giving up their land. Many Cherokee were still on their land in 1838 when the U.S. Army was sent to evict them and send them on a terrible journey to Indian Territory. Disease, hunger, and cold weather led to the deaths of thousands along the trail the Cherokee came to call the “Trail of Tears.” A small band of Cherokee who refused to comply with forced removal escaped into the Smoky Mountains, where their descendants still live. The lands taken from the Cherokee were quickly sold by the state to settlers, who turned Chief John Ross’s Landing into the town of Chattanooga.

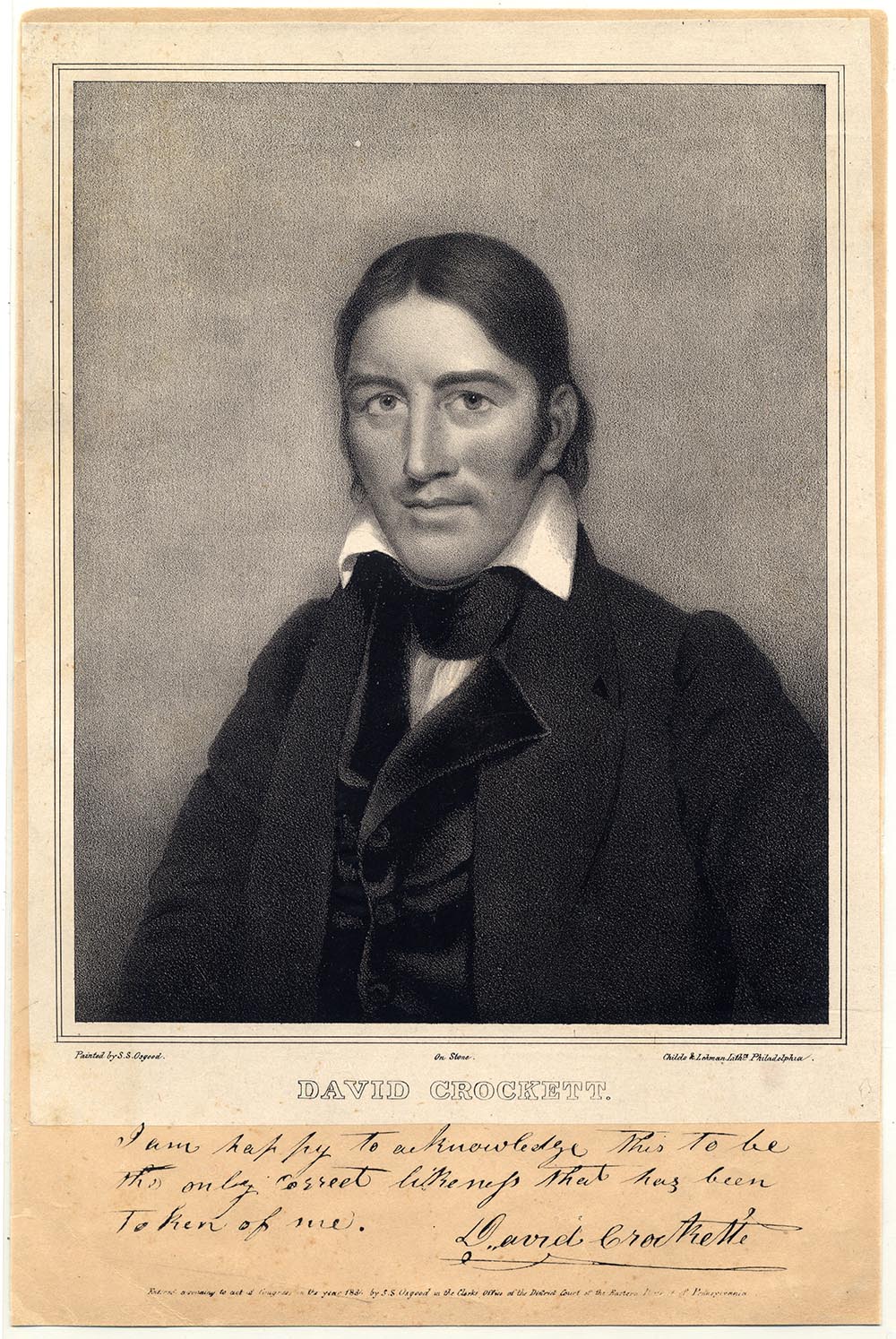

Several other leading Tennessee politicians developed their careers in opposition to Jackson and his Democratic party. William Carroll served six terms as governor, from 1821 through 1835, despite a lack of support from Jackson. David Crockett, Hugh Lawson White, Ephraim Foster, James C. Jones, Newton Cannon, and John Bell also rose in power while opposing the Democrats. Some businessmen resented Jackson’s war on the national bank. Others felt excluded from Jackson’s inner circle of political allies. Many Tennesseans in the Eastern Division favored using government money for internal improvements such as roads, bridges, and railroads. They also wanted government to assist the growth of industry. Jacksonian Democrats generally opposed spending government money in these ways. As a result, Andrew Jackson’s home state became a birthplace of the anti-Jackson Whig Party. The Whigs took their name from a political party in England that opposed the king. Whig candidates for governor won six out of nine elections between 1836 and 1852, but all of the elections were extremely close. Whigs also carried Tennessee in six consecutive presidential elections. The state went so far as to vote against Tennessee Democrat James K. Polk for president in 1844. Voter participation rates reached all-time highs during this time period. The two political parties competed fiercely for votes through newspapers, barbecues, and stump speeches. Stump speeches are standard speeches used by a politician running for office. The speeches got their name because candidates would often stand on stumps to help their voices carry while speaking to large crowds.

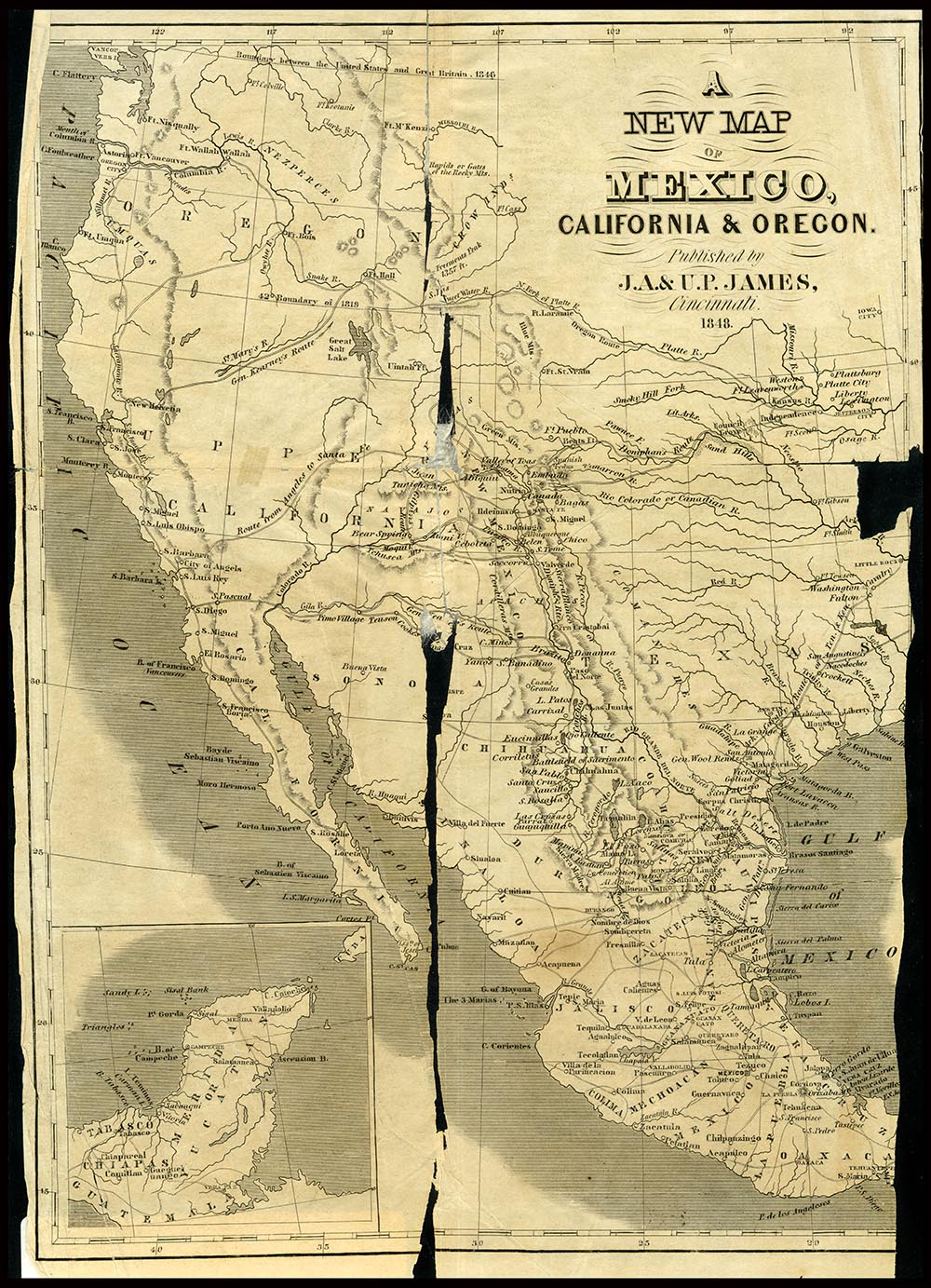

Tennessee earned the nickname “Volunteer State” during this period for its role in America’s wars of expansion. Tennesseans played important roles in the War of 1812, the Texas Revolution, the Seminole Wars, and the Mexican War. Jackson and his troops saved the Gulf Coast from British claims and forced Native American tribes to give up major portions of Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky. Jackson’s 1818 expedition into Florida resulted in that territory becoming part of the United States. In 1836, Tennesseans David Crockett and Sam Houston led the fight for Texan independence. Crockett died at the Alamo, but Houston led the Texans to victory at San Jacinto and later became president of the Lone Star Republic. Tennesseans volunteered in large numbers for the war with Mexico and played key roles in several battles. Perhaps the ultimate military adventurer was Nashvillian William Walker. During the 1850s, Walker led several expeditions to create independent, slaveholding republics in Lower California and Central America.

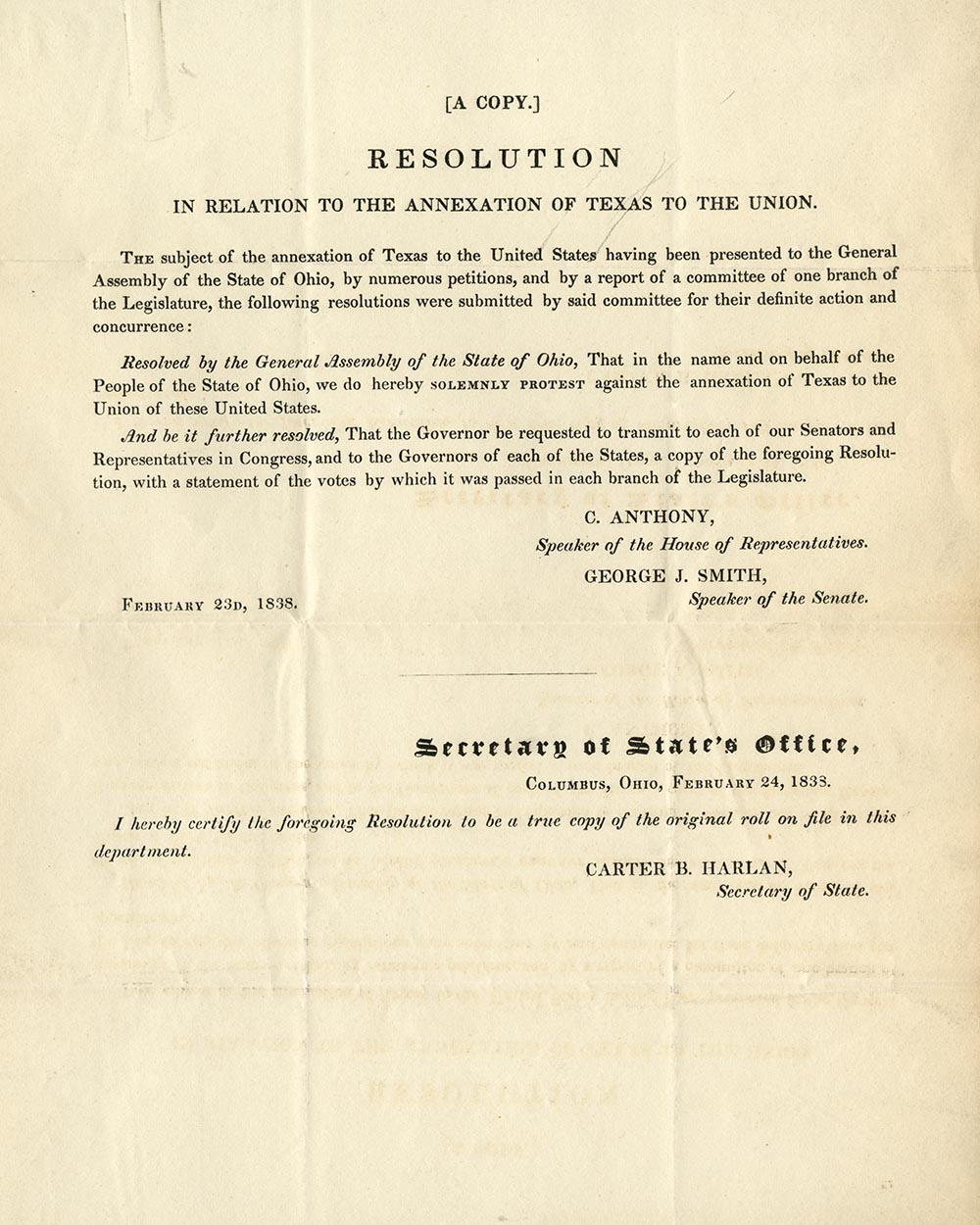

Tennessee politicians also played a key role in the expansion of the United States’ boundaries. Felix Grundy declared in 1811 that he was “anxious not only to add the Floridas to the South, but the Canadas to the North of this empire.” Tennessee’s congressional representatives were leading “War Hawks” in 1812 and throughout the conflict with Mexico. Having already removed Native Americans from millions of acres of land, Jackson’s final act as president was to recognize the Lone Star Republic. When James K. Polk of Maury County was elected president in 1844, his first act was to annex, or add, Texas to the United States. The Mexican War was primarily a war of Southern expansion. By the end of the war, the United States had gained California, the New Mexico territory, and Oregon. Tennessee politicians believed in the idea of manifest destiny and played key roles in the nation’s expansion. Most Tennesseans resented anti-slavery Northerners who raised the issue of banning slavery in the new territories in the Wilmot Proviso.

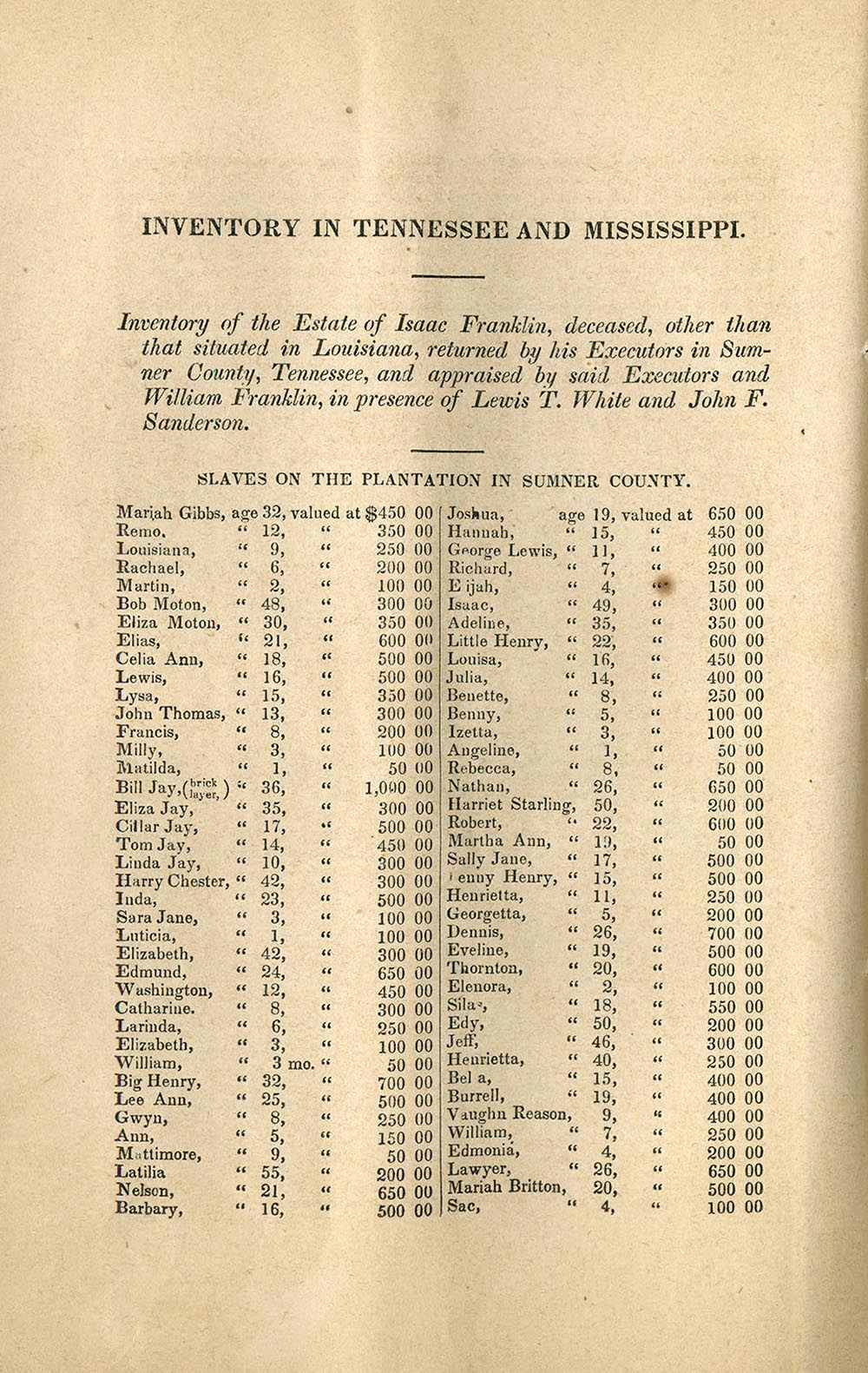

The Wilmot Proviso did not pass, but it demonstrated the deep division in the country over slavery. Tennessee’s slave population had increased from 22.1 percent of the population in 1840 to 24.8 percent in 1860. Ownership of slaves was concentrated in relatively few hands: only 4.5 percent of the state’s white population were slaveholders in 1860. As the demand for cotton increased, the cost of slaves also increased. Nashville and Memphis were renowned centers of the slave trade. The profitability of cotton and slave labor made planters determined to resist Northern attacks on slavery.

In the early 1830s, two events caused Tennessee to tighten laws related to enslaved individuals and free African Americans. The Virginia slave uprising led by Nat Turner badly frightened slave owners. White Tennesseans reacted by stepping up “patrols” for runaways and tightening the rules regulating conduct of the enslaved, assembly, and movement. The state Constitution was amended in 1834 to prevent free African Americans from voting. Free African Americans were pressured to leave the state, and rumors of planned slave insurrections, or rebellions, kept tensions high. By the 1850s, Tennessee was sharply divided between anti-slavery advocates in East Tennessee and diehard defenders of slavery in West Tennessee. From 1848 onward, slavery overshadowed other political issues. Political parties and church denominations broke apart over slavery. Newspapers waged a vicious war of words over abolitionism and the fate of the Union. Southern delegates met in Nashville in 1850 to express their anger over Northern interference in slavery. Tennessee’s economic and social ties with the Lower South meant the state was mostly pro-slavery. However, Tennessee had a long tradition of military and political service to the nation. Therefore, most Tennesseans did not support secession. Tennessee and the rest of the country stood on the brink of disaster in 1860.